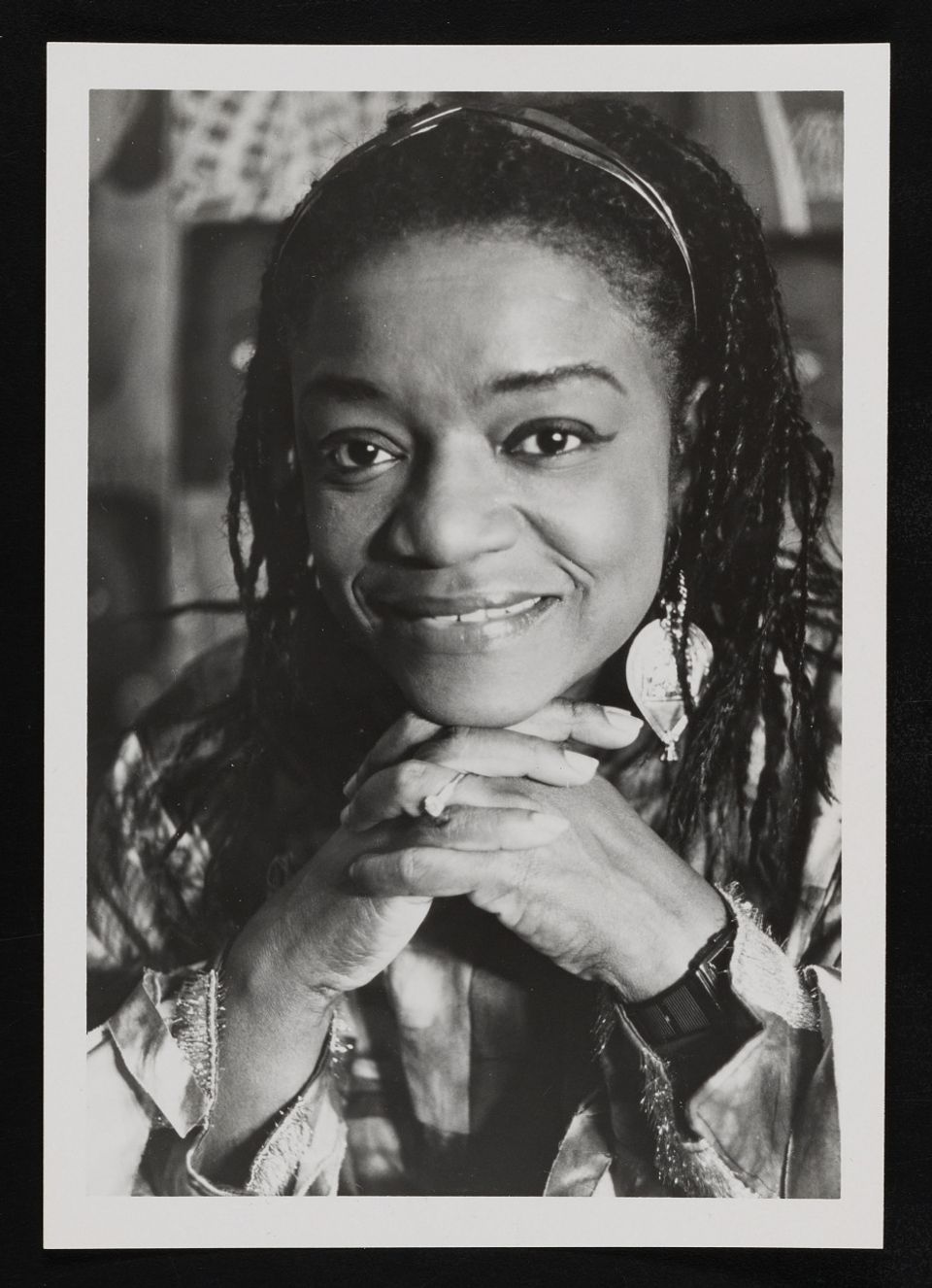

Faith Ringgold

Photograph of Faith Ringgold, circa 1987. Woman's Building records, 1970-1992, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- Died

- Englewood, New Jersey, United States

- Active in

- San Diego, California, United States

- Biography

"I think of my art as my voice. It's what I have to say about the world I live in, and it's about who I am and what I would like things to be. Art is my voice. And I'm going to say what I want to say, no matter what people tell me to do."

–– Faith Ringgold, 2022

Faith Ringgold was an artist, activist, author, and educator who joined elements from history and culture with her autobiography to address interconnected issues of racism and sexism. Through narrative-driven paintings, quilts, performances, and sculptures, Ringgold celebrated the joyous and everyday facets of Black American life.

Raised in Harlem, Ringgold was immersed in the Black artistic and cultural flourishing known as the Harlem Renaissance. Intermittently homeschooled due to asthma, she learned to sew from her mother and fashion designer, Madame Willi Posey. In the 1950s, Ringgold completed undergraduate and graduate degrees in art at the City College of New York's School of Education (1955, 1959). By 1955, she was married with two daughters and taught in public schools while painting landscapes grounded in her Eurocentric education.

Amid the rise of the civil rights movement of the 1960s, Ringgold turned to politically engaged subject matter. She devised her own "Super Realism" style in 1963, depicting Black and white figures in scenes that probed racism to represent, in her words, "what it was like living in America at the time." By mid-decade, in response to the Black Power movement's embrace of racial pride, Ringgold examined the multiple social and formal resonances of the color black in the series Black Light (1967–69).

By 1968, Ringgold actively contributed to artist-led antiwar and antiracist protests at major museums, and in the 1970s, focused on feminist politics, co-founding Black women's groups like the Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation with her daughter, Michele Wallace. During this period, she designed posters, like Woman Free Yourself (1971, Cooper Hewitt), that featured political statements in triangulated patterns inspired by African Kuba textiles. By 1972, she began collaborating with her mother on feminist soft sculptures and unstretched paintings based on the form of thangkas, Tibetan and Nepalese paintings that can be rolled up.

In 1980, Ringgold made her first quilt with her mother, who passed away shortly thereafter. She reflected, "It was as if I, with all my story-tellers gone, was now authorized to be one." Ringgold struggled to publish her autobiography and turned to performance as an alternate mode of storytelling, blending her personal experiences with history, culture, and fiction. By 1983, she began to write these stories directly onto her painted quilts to create what she termed "story quilts," as in The Bitter Nest, Part II: The Harlem Renaissance Party (1988, SAAM).

In 1990, Ringgold initiated her most ambitious tribute to her mother through The French Connection (1990–97). This twelve-part story quilt narrates the journey of Willia Marie Simone from Harlem to Paris in the 1920s, emphasizing her encounters with European artists and influential Black women, as in Jo Baker’s Birthday (1995, SAAM). Ringgold continued creating story quilts in her late career, and their subject matter ranged from childhood memories to legacies of racism and sexism in the United States.

For seven decades, Ringgold utilized her art, life, and voice to advocate for social equity and critically intervene in dominant histories of the United States and American art. "I thought that art records history and records the present," she stated, "So that's what I think I was doing: recording."

Authored by Gabriella Shypula, American Women's History Initiative Writer and Editor, 2024.