Artworks by African Americans from the Collection

The Smithsonian American Art Museum is home to an extraordinary collection of artworks by African Americans with more than 2,000 objects by more than 200 artists.

In celebration of the 2016 Grand Opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, SAAM will display 184 of its most important artworks by African Americans, adding 48 objects to the 136 currently on view in the galleries throughout the museum’s building and Luce Foundation Center.

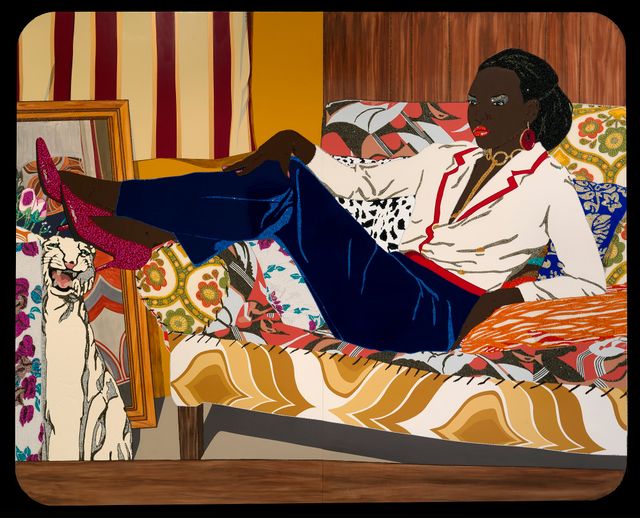

From William H. Johnson’s vibrant portrayals of faith and family to Mickalene Thomas’s contemporary exploration of black female identity, SAAM’s holdings reflect its long-standing commitment to black artists and the acquisition, preservation, and display of their works.

Description

The featured artworks cover centuries of creative expression, powerfully evoking themes both universal and specific to the African American experience. They include painting, sculpture, and textiles, and represent numerous artistic styles, ranging from realism to neoclassicism, abstract expressionism and modernism. Many mirror the tremendous social and political change occurring during the Jazz Age and Harlem Renaissance, the post-war years and the civil rights movement into present day.

A number of works, including James Hampton’s iconic The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations' Millennium General Assembly (1950–64), are included in the museum’s folk and self-taught art galleries, which reopened to the public October 21, 2016 following a major reinstallation.

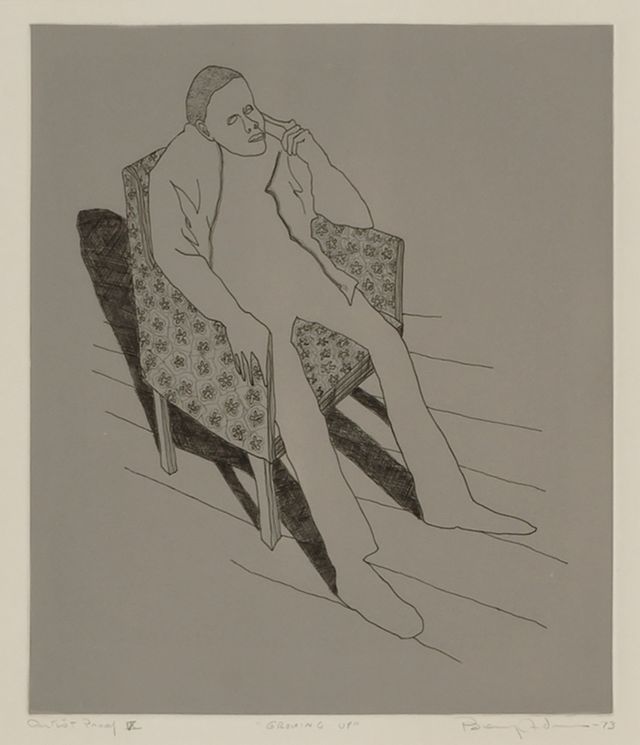

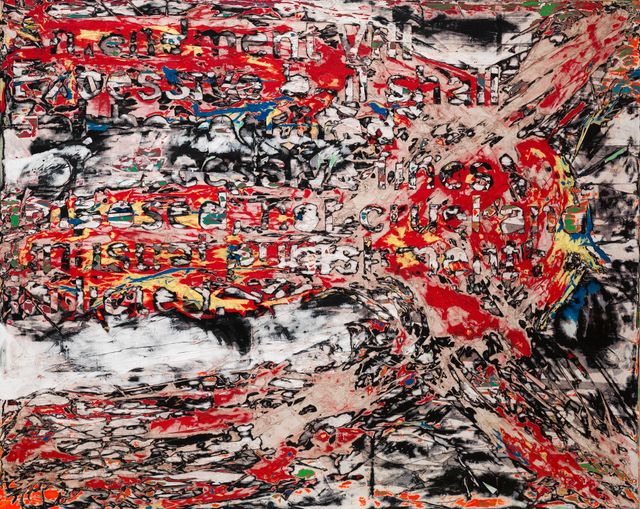

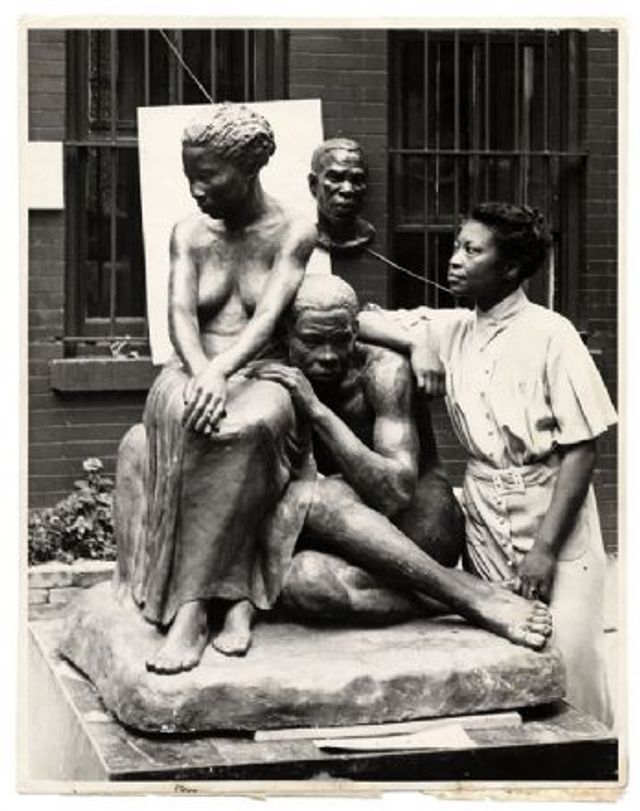

Visitor favorites by Loïs Mailou Jones and Jacob Lawrence; abstractions by Washington’s own Sam Gilliam, Felrath Hines and Alma Thomas; contemporary works by Mark Bradford, Faith Ringgold and Mickalene Thomas; key pieces by self-taught artists such as Clementine Hunter and Purvis Young; and influential works by Benny Andrews, John Biggers, Edmonia Lewis and Augusta Savage are included in the installation. A selection from the museum’s in-depth collections of works by William H. Johnson and Henry Ossawa Tanner are displayed throughout the galleries and in the Luce Foundation Center.

Visiting Information

Videos

Online Gallery

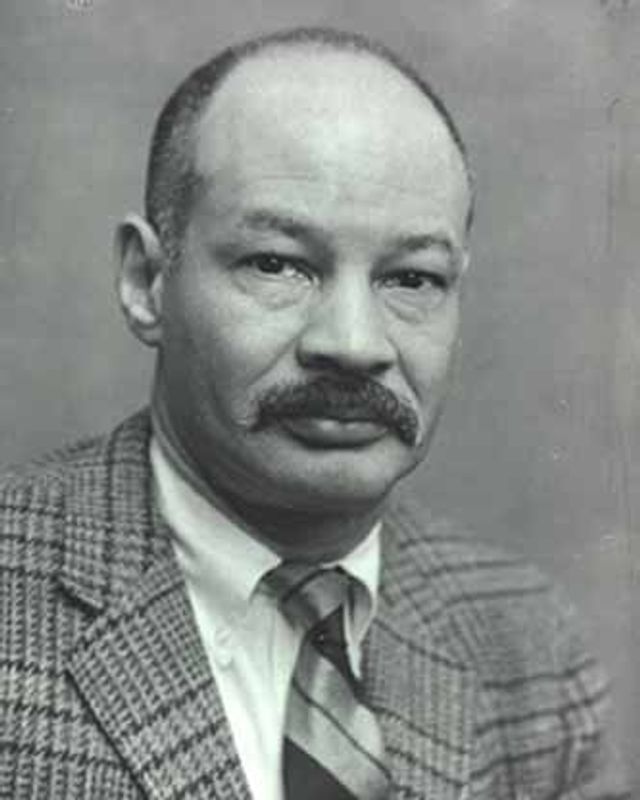

Artists

Gilliam is an innovative color field painter who has advanced the inventions associated with the Washington Color School.

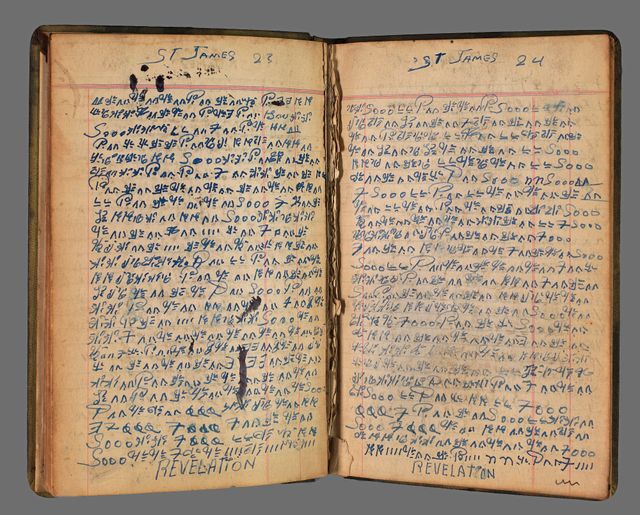

Little is known about James Hampton, despite the grandeur of his self-chosen title, "Director, Special Projects for the State of Eternity." He was born in 1909 in Elloree, South Carolina, a small community of predominantly African-American sharecropper

Painter. Hines studied design at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, N.Y., and his paintings—in the tradition of the De Stijl movement—often contain strong design elements.

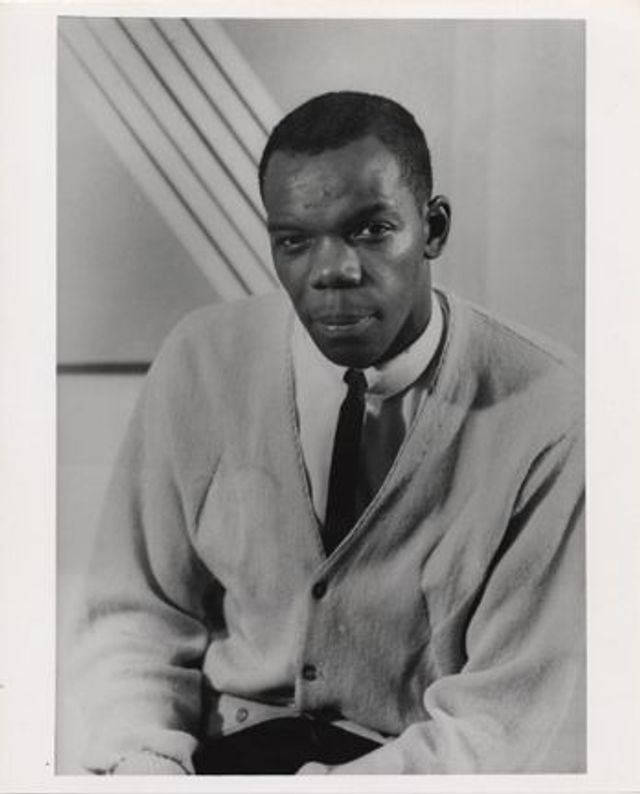

By almost any standard, William H. Johnson (1901–1970) can be considered a major American artist. He produced hundreds of works in a virtuosic, eclectic career that spanned several decades as well as several continents.

Now in her eighth decade as an artist, Lois Mailou Jones has treated an extraordinary range of subjects—from French, Haitian, and New England landscapes to the sources and issues of African-American culture.

Painter. A social realist, Lawrence documented the African American experience in several series devoted to Toussaint L'Ouverture, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, life in Harlem, and the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

"I have created nothing really beautiful, really lasting, but if I can inspire one of these youngsters to develop the talent I know they possess, then my monument will be in their work."—T. R.

Working in France after 1891, Henry Ossawa Tanner achieved an international reputation largely through his religious paintings.

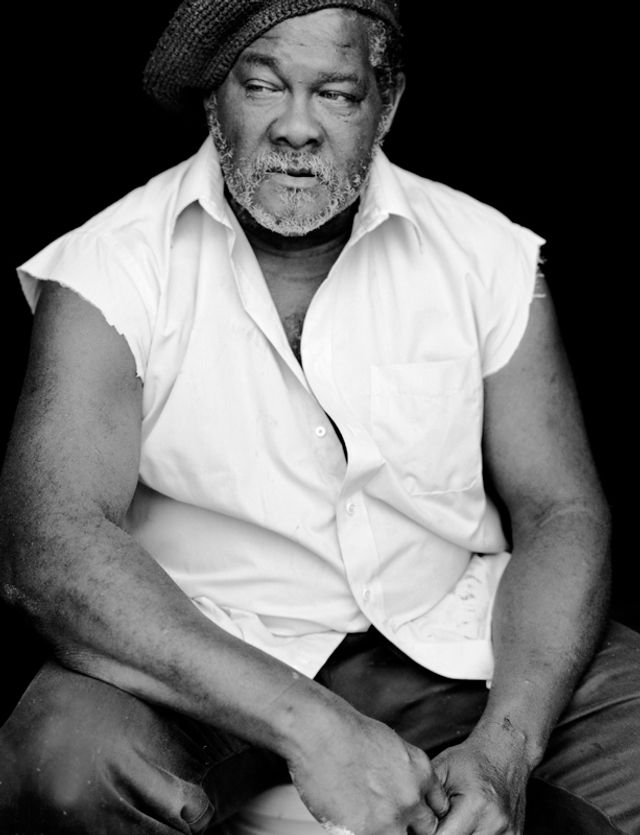

Purvis Young paints on scrap lumber and plywood that he scavenges from the streets and vacant lots of Overtown, the historically black neighborhood where he lives in Miami, Florida, and whose long deterioration he has witnessed.