ADÁL

- Also known as

- Adal Maldonado

- Adal Alberto Maldonado

- Adal

- Born

- Utuado, Puerto Rico

- Died

- San Juan, Puerto Rico

- Active in

- New York, New York, United States

- Digital Catalogue

- Musical Thinking: New Video Art and Sonic Strategies

- Biography

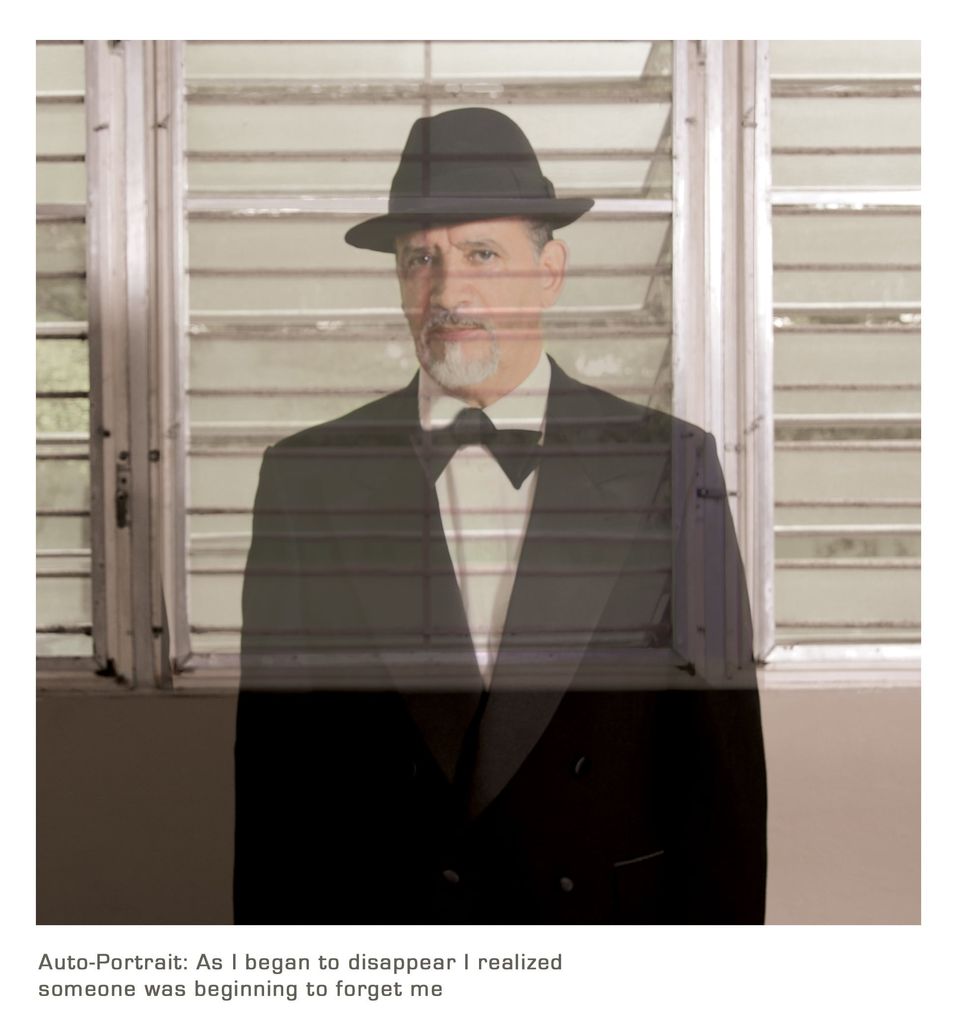

ADÁL was a photographer, installation and performance artist, and political provocateur. Born Adalberto Maldonado in a mountainous region of Puerto Rico, ADÁL moved to the New York metro area as a teenager with his family. This fundamental experience of dislocation and reorientation laid the ground for a career spent exploring the conceptual slipperiness of identity and, as he proclaimed, “the impossibility of ever achieving a definitive picture of one’s self.”

After studying art and design in California, he returned to New York City in the mid-1970s and cofounded and codirected Foto Gallery in SoHo. Through his own work and this platform, ADÁL promoted experimental photography and a diversifying art canon. He was a leading force in the Nuyorican scene—a movement that celebrates a hybrid New York-Puerto Rican identity and the creative contributions of this community, while critiquing the colonial conditions that produced it.

ADÁL received acclaim for several collective photographic series that highlight Puerto Rican diasporic artists, performers, and intellectuals who, like him, straddled multiple worlds, and for his surreal self-portraits that subvert expectations of uncovering a true self through photography. Into the 1990s and 2000s, he mixed photography, performance, political theater, and happenings to continue the work of decolonizing minds, bodies, and spirits. With poet Pedro Pietri, he cofounded El Puerto Rican Embassy Project, creating passports, anthems, evidence of a space program, and more from an imagined liberated nation. They also produced musical theater projects centering mambo, originally an Afro-Cuban music genre, as a tool of emancipation. ADÁL’s final series, Puerto Ricans Underwater/Los Ahogados (The Drowned) (2016–19) portrays a community still struggling under colonialism by photographing island residents eerily submerged in water.

Regularly included in group exhibitions, his work has also been shown in solo presentations at El Museo del Barrio in New York, and the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies at Harvard University. His work is in numerous public collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris.