Arthur Jafa

- Also known as

- Arthur Jaffa

- Arthur Jafa Fielder

- Born

- Tupelo, Mississippi, United States

- Digital Catalogue

- Musical Thinking: New Video Art and Sonic Strategies

- Biography

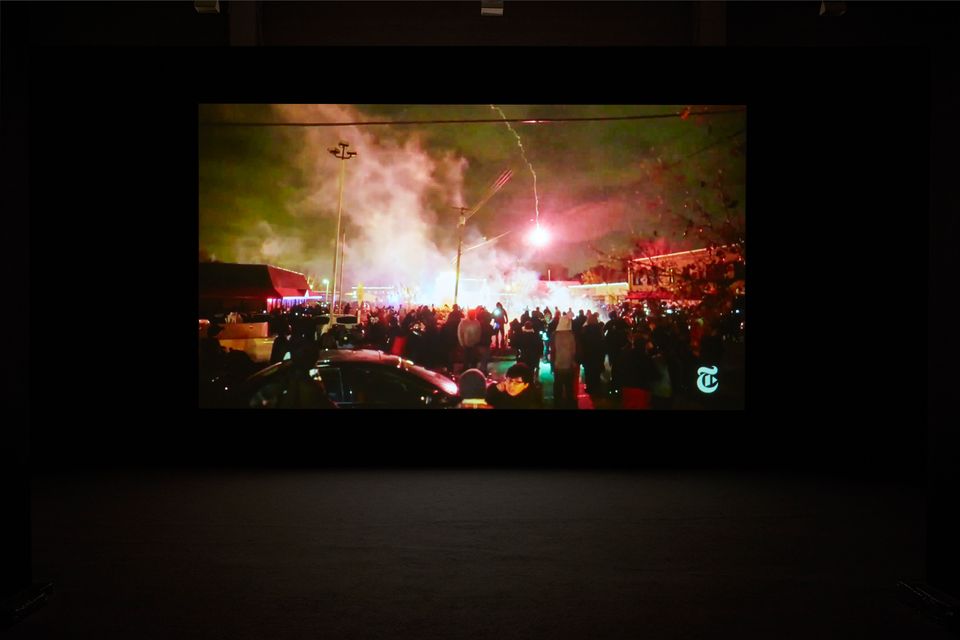

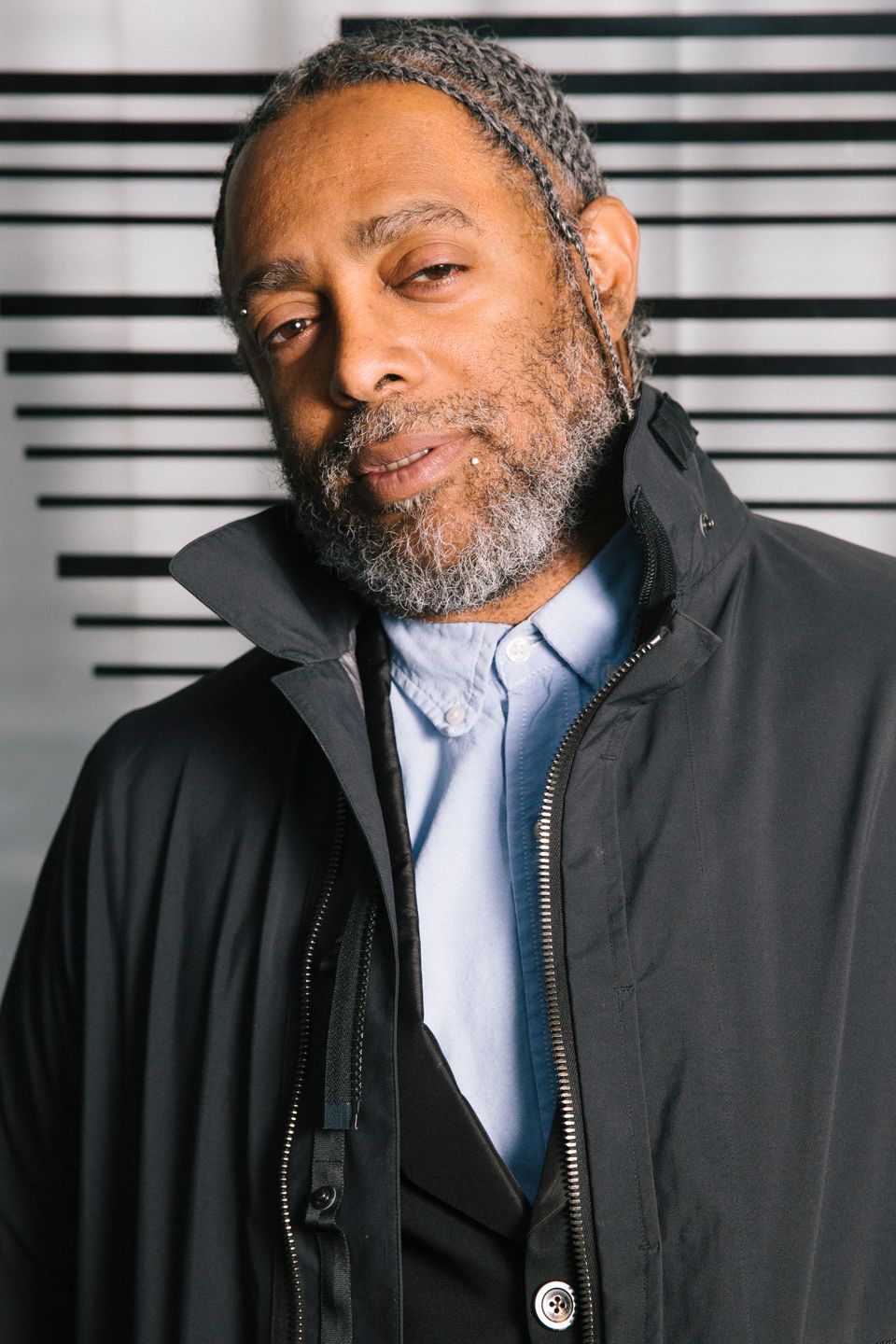

Arthur Jafa is an artist, filmmaker, and cinematographer. Across three decades, Jafa has developed a dynamic practice comprising films, artefacts, and happenings that reference and question the universal and specific articulations of Black being. Underscoring the many facets of Jafa's practice is a recurring question: How can visual media, such as objects, static and moving images, transmit the equivalent "power, beauty, and alienation" embedded within forms of Black music in US culture?

Growing up between Tupelo and the Mississippi Delta, Jafa describes being “very much shaped by bouncing [back] and forth between those communities,” where desegregation and continued segregation were in tension. He studied architecture and film at Howard University in DC, before moving to Los Angeles to focus on filmmaking. His first feature as a cinematographer, the art-house icon Daughters of the Dust (dir. Julie Dash, 1991), won him Best Cinematographer at the Sundance Film Festival, and he went on to shoot films for directors Stanley Kubrick, Spike Lee, and Ava DuVernay. Beginning around 2000, he also began showing short videos, sculptures, and photo collages in art contexts, where he has received increasing acclaim.

Solo exhibitions of Jafa’s work have been organized by London’s Serpentine Gallery, the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark. In 2019, he received the Golden Lion for Best Participant of the 58th Venice Biennale. In the summer of 2020, Jafa worked with a global consortium of art museums and institutions to live stream Love is the Message, The Message is Death in alignment with global uprisings for racial justice. Jafa's films screen at the Los Angeles, New York, and Black Star Film festivals, and his artwork is in celebrated collections worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Tate Modern, London; the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; and the LUMA Foundation, in Zurich and Arles.

- Artist Biography

Arthur Jafa (b. 1960, Tupelo, Mississippi) is an artist, filmmaker and cinematographer. Across three decades, Jafa has developed a dynamic practice comprising films, artefacts and happenings that reference and question the universal and specific articulations of Black being. Underscoring the many facets of Jafa's practice is a recurring question: how can visual media, such as objects, static and moving images, transmit the equivalent "power, beauty, and alienation" embedded within forms of Black music in U.S. culture?

Jafa's films have garnered acclaim at the Los Angeles, New York and Black Star Film Festivals and his artwork is represented in celebrated collections worldwide including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, Tate, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Studio Museum in Harlem, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, the Dallas Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Luma Foundation, the Perez Art Museum Miami, The Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, among many others.

Jafa has recent and forthcoming exhibitions of his work at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archives; Moderna Museet, Stockholm; Fundacao de Serralves, Porto; the 22nd Biennale of Sydney; and the Louisiana Museum of Art, Denmark. In 2019, he received the Golden Lion for the Best Participant of the 58th Venice Biennale "May You Live in Interesting Times."

Videos

Exhibitions

Related Posts