From the collections of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. Funding provided by Joseph H. Hirshhorn Bequest Fund; Gift of Nion T. McEvoy, Chair of SAAM Commission (2016-2018) and McEvoy’s fellow Commissioners in his honor.

Last year, SAAM jointly acquired acclaimed filmmaker, artist, and cinematographer Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, The Message is Death with the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. I am thrilled that Jafa will be at SAAM this upcoming weekend to talk about his work in dialogue with the brilliant next-gen auteur Ja’Tovia Gary. As a prelude to this electrifying program, I want to share the importance of SAAM as a context for Jafa’s powerful work.

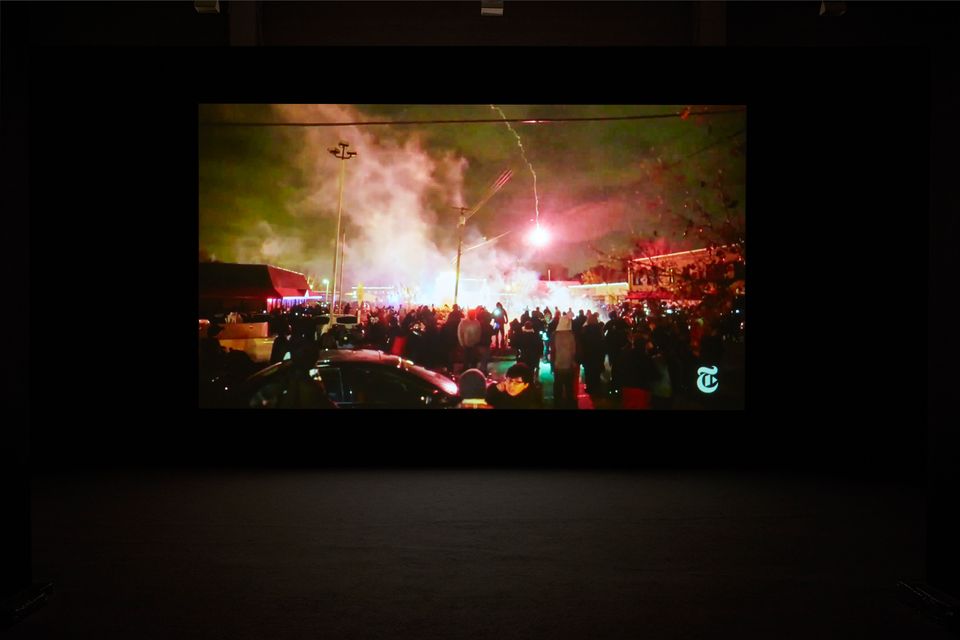

In 2016, when Jafa debuted Love is the Message, The Message is Death, it was instantly recognized as one of the most important artworks of the past decade (and more recently was named in the New York Times as one of 25 works that define the contemporary age). It offers a profoundly moving montage of original and found footage exploring the mix of joy and pain, transcendence and tragedy that constitutes the African American experience at this historical moment. Set to Kanye West’s gospel-inflected song “Ultralight Beam,” the piece swells with spiritually uplifting but candid lyrics; the music occasionally recedes allowing poignant snippets of dialogue to come to the fore. Writing in Artforum, critic Tobi Haslett noted, “Jafa’s juxtapositions rise above cleverness but shrink from sentimentalism, constructing a picture of Blackness that manages to fold a whole emotional galaxy—glory, disappointment, buffoonery, lust, poise—into seven minutes of mass-market pop.”

This tightly-controlled editing echoes the intricate rhythmic structures of jazz and hip-hop, exemplifying Jafa’s stated goal of creating a cinema that “replicates the power, beauty and alienation of Black Music.” Through his visual selection, Jafa perfectly captures the range of media sources and ideological mediation through which contemporary viewers experience and understand their world. Iconic images of civil rights leaders overlaid with gettyimages® raise questions of corporate co-option. Sensationalized news and sports coverage interrogates cultural constructions of Blackness. Camera-phone-recorded YouTube videos highlight how our most personal moments can now become shockingly public, whether through choice or necessity.

Given the significance of this piece, it seemed ideal for it to be in the collections of both the Hirshhorn, with its mission of presenting defining works of contemporary art, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, dedicated to showcasing the breadth and brilliance of American art as it illuminates the American experience.

For me, SAAM’s participation was important for another reason that I hinted at when I told Smithsonian magazine that Jafa’s video struck me as a “contemporary Guernica,” a reference echoed in a recent New York Times profile on the artist. The comparison is to a famous mural painted by Spanish artist Pablo Picasso in 1937, depicting the destruction wrought by the aerial bombing of civilians, mostly women and children, in the northern town of Guernica. The attack was carried out by Nazi warplanes at the invitation of Spain’s fascist military-coup leader General Francisco Franco, and was widely considered a terrorist escalation of the civil war already tearing the country apart. Picasso started the composition shortly after the attack, and the piece debuted just months later, at the Spanish Pavilion in the Paris International Expo, where its moral call to the world was unmistakable. It is often cited as one of the greatest anti-war artworks, an example of an artist using their creative, communicative power to move us beyond the desensitizing news cycles and towards feeling connected with those at the core of events.

There are many parallels that can be made between the process, intentions and impact of Guernica and Love is the Message, The Message is Death. Both were made with a sense of urgency, in response to and in the midst of an ongoing crisis. Both use fragmentation and re-composition to get us to look anew at images circulating in mass media, images that hit differently when broken up and reordered, when blown-up to fill a wall and punctuated by moments of raw pain and aching beauty. And now there is also the fact they are both in the national collections of the countries whose actions are being interrogated.

When arguing for why SAAM should partner with the Hirshhorn on this, I thought often of how it had felt to see Guernica at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid. Since 1939, per Picasso’s wishes, the painting had been entrusted to the Museum of Modern Art in New York and was not to be given to Spain until a republic with “public liberties and democratic institutions” was restored. After Franco’s death and a new constitution was ratified, the painting came to Spain for the first time in 1981, and was installed in the national museum in a purpose-built gallery in 1992. It now is shown surrounded by related works of art and architectural diagrams of its first presentation, but also documentary war photographs, contemporaneous journals and protest posters that powerfully attest to the decades of struggle and the multitude of voices that joined Guernica in decrying fascism and the brutalization of fellow citizens, and continued to demand better of the government and each other until Picasso’s terms for this painting’s “return” to Spain were met. Here it is not an abstract anti-war message, not just a modernist masterpiece, but a specific address to a specific community, a reminder of unresolved histories and a warning to consider what might come of future actions, of ongoing failures to see each other as equal and intimately connected.

In thinking of Jafa’s video being part of SAAM’s national collection, I think of what context we might give it, forty years into the future; will we be able to show it as one part of a struggle to shift the way we treat each other, the way the government treats its citizens, and will we be able to say things have changed for the better? I hope that as our Guernica, Love is the Message, The Message is Death is someday a cautionary reminder of where we’ve been as a country; an admonition that constitutional promises of public liberties and democratic institutions are not the same as having them, that these promises required centuries of struggle to become real and to not take them—should we ever attain them—for granted.

On Saturday, October 12 at 3 p.m. in SAAM’s McEvoy Auditorium, Arthur Jafa and fellow artist and filmmaker Ja’Tovia Gary will explore the interplay of black identity, music, and moving images across their creative careers through conversation and clip sharing.