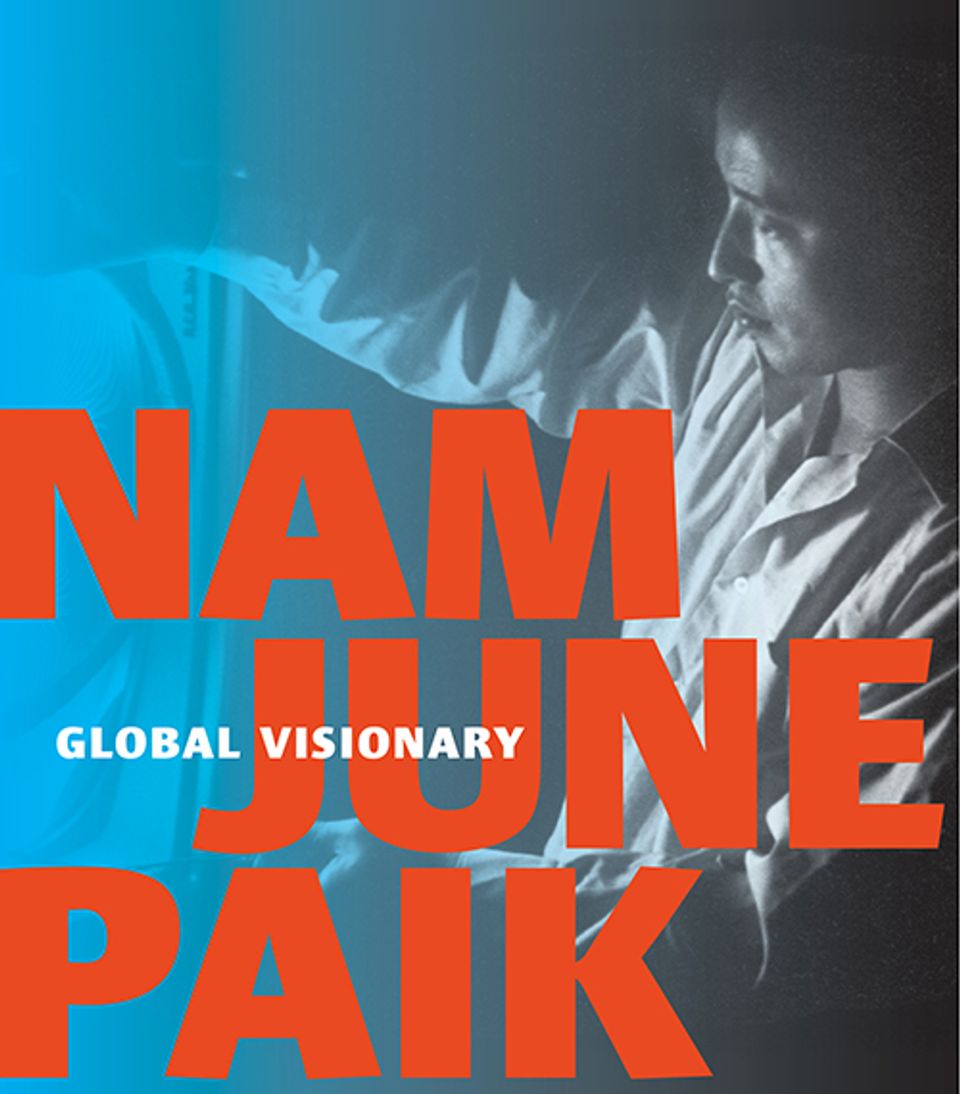

Nam June Paik

- Born

- Seoul, Korea

- Died

- Miami Beach, Florida, United States

- Active in

- New York, New York, United States

- Biography

Nam June Paik (1932–2006), internationally recognized as the "Father of Video Art," created a large body of work including video sculptures, installations, performances, videotapes and television productions. He had a global presence and influence, and his innovative art and visionary ideas continue to inspire a new generation of artists.

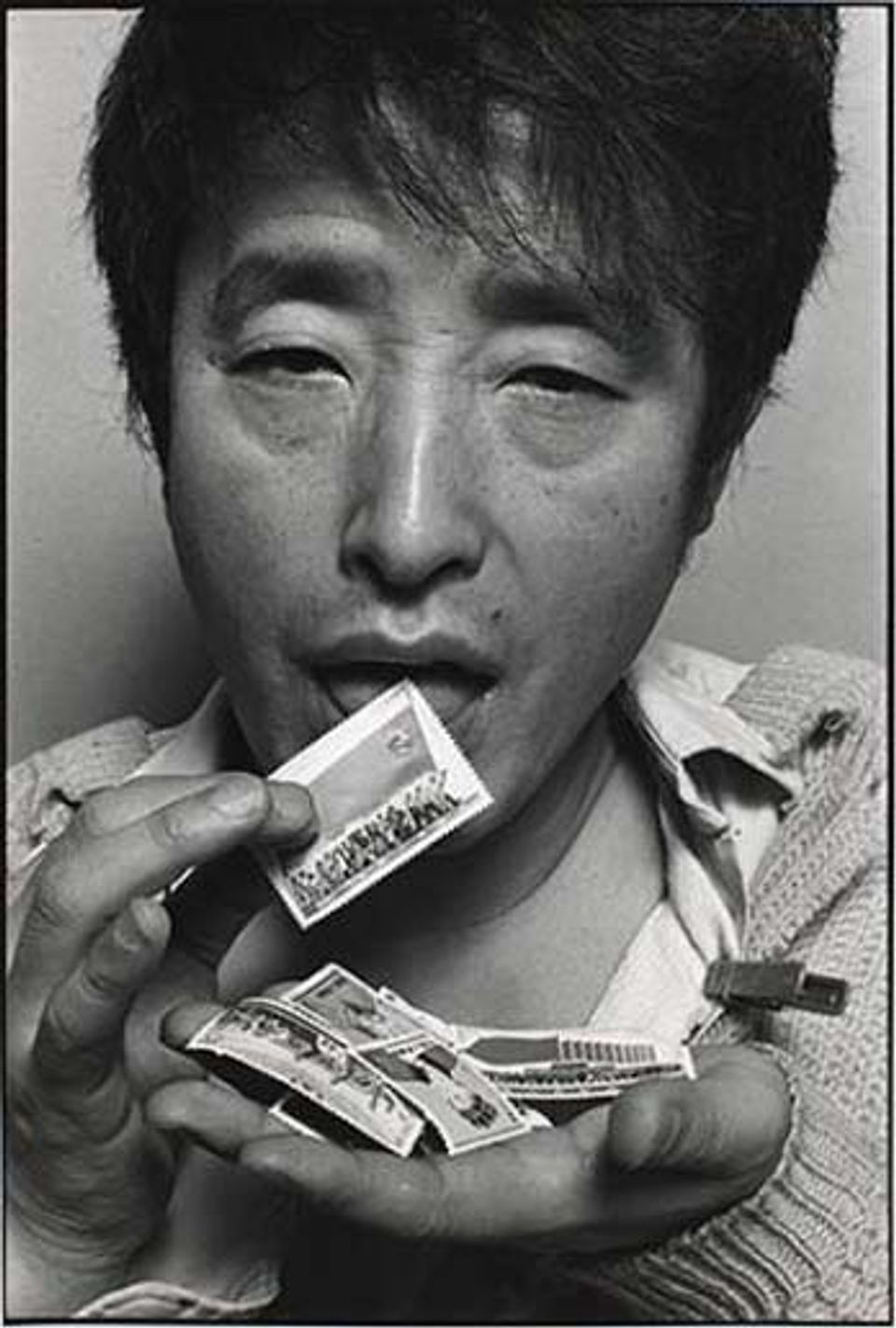

Born in 1932 in Seoul, Korea, to a wealthy industrial family, Paik and his family fled Korea in 1950 at the outset of the Korean War, first to Hong Kong, then to Japan. Paik graduated from the University of Tokyo in 1956, and then traveled to Germany to pursue his interest in avant-garde music, composition and performance. There he met John Cage and George Maciunas and became a member of the neo-dada Fluxus movement. In 1963, Paik had his legendary one-artist exhibition at the Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal, Germany, that featured his prepared television sets, which radically altered the look and content of television.

After immigrating to the United States in 1964, he settled in New York City where he expanded his engagement with video and television, and had exhibitions of his work at the New School, Galerie Bonino and the Howard Wise Gallery. In 1965, Paik was one of the first artists to use a portable video camcorder. In 1969, he worked with the Japanese engineer Shuya Abe to construct an early video-synthesizer that allowed Paik to combine and manipulate images from different sources. The Paik-Abe video synthesizer transformed electronic moving-image making. Paik invented a new artistic medium with television and video, creating an astonishing range of artworks, from his seminal videotape Global Groove (1973) that broke new ground, to his sculptures TV Buddha (1974), and TV Cello (1971); to installations such as TV Garden (1974), Video Fish (1975) and Fin de Siecle II (1989); videotapes Living with the Living Theatre (1989) and Guadalcanal Requiem (1977/1979); and global satellite television productions such as Good Morning Mr. Orwell, which broadcast from the Centre Pompidou in Paris and a WNET-TV studio in New York City Jan. 1, 1984.

Paik has been the subject of numerous exhibitions, including two major retrospectives, and has been featured in major international art exhibitions including Documenta, the Venice Biennale and the Whitney Biennial. The Nam June Paik Art Center opened in a suburb of Seoul, South Korea, in 2008.

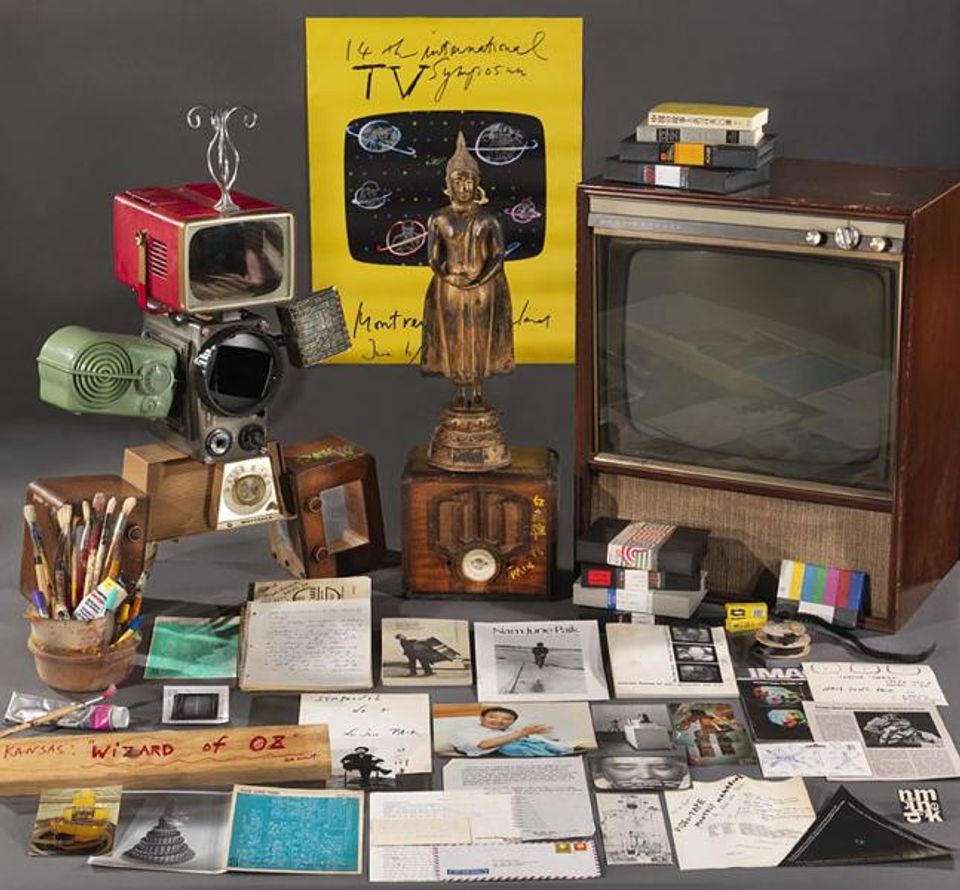

Smithsonian American Art Museum "The Smithsonian American Art Museum Acquires the Complete Estate Archive of Visionary Artist Nam June Paik" (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian American Art Museum, press release, May 1, 2009)

Videos

Exhibitions

Related Books

Related Posts