SAAM’s landmark exhibition, ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now, explores how Chicanx artists have linked innovative printmaking practices with social justice. This blog post is part of series that takes a closer look at selected artworks with material drawn from exhibition texts and the catalogue.

In the late 1990s, Pepe Coronado, a Dominican American artist living in Austin, Texas, joined the Serie Project, a Chicano print residency, as a master printer. The collaborative spirit and artistic vision he witnessed among Chicano and other Latino artists in residence at the print center left a strong impression. Based in part on this experience, Coronado later founded the Dominican York Proyecto GRAFICA (DYPG) in New York City, a print collective dedicated to exploring Dominican American culture and history. ¡Printing the Revolution! features Manifestaciones, the first portfolio produced by the twelve artists in the group.

Modest in scale but bold in concept, Manifestaciones tackles topics from the 1965 U.S. intervention in the Dominican Republic to the persistence of racist colorism in Dominican society. It examines the transplantation of island icons to an urban context and the remapping of NY into a hybrid Dominican American space. All of these subjects conceptually relate to the bicultural and borderland undercurrents of Chicanx art.

Below are a few highlights from the portfolio.

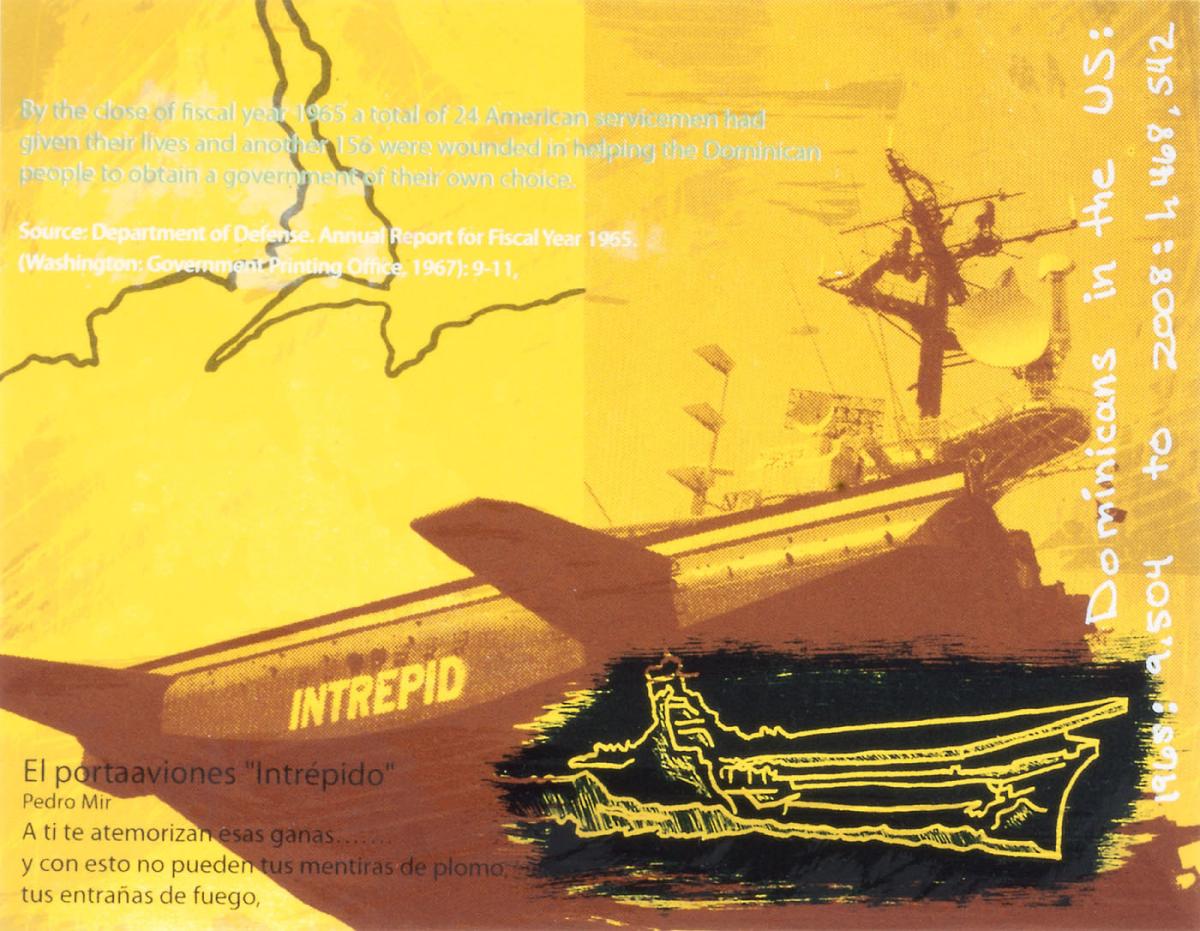

In Pepe Coronado’s print Intrépido, the artist juxtaposes texts that comment on the 1965 U.S. intervention in the Dominican Republic against an image of the USS Intrepid, a U.S. naval ship active during World War II and the Cold War. On the top of the print, Coronado quotes a Department of Defense report framing the intervention in altruistic terms. Near the bottom, he excerpts lines from Pedro Mir’s “El Portaaviones Intrépido” (The Intrepid Aircraft Carrier), a poem that defiantly calls out the carrier’s role in U.S. wars abroad. On the right-hand side of the print, Coronado records the increasing number of people of Dominican descent in the United States since 1965, linking U.S. foreign policies and immigration spikes.

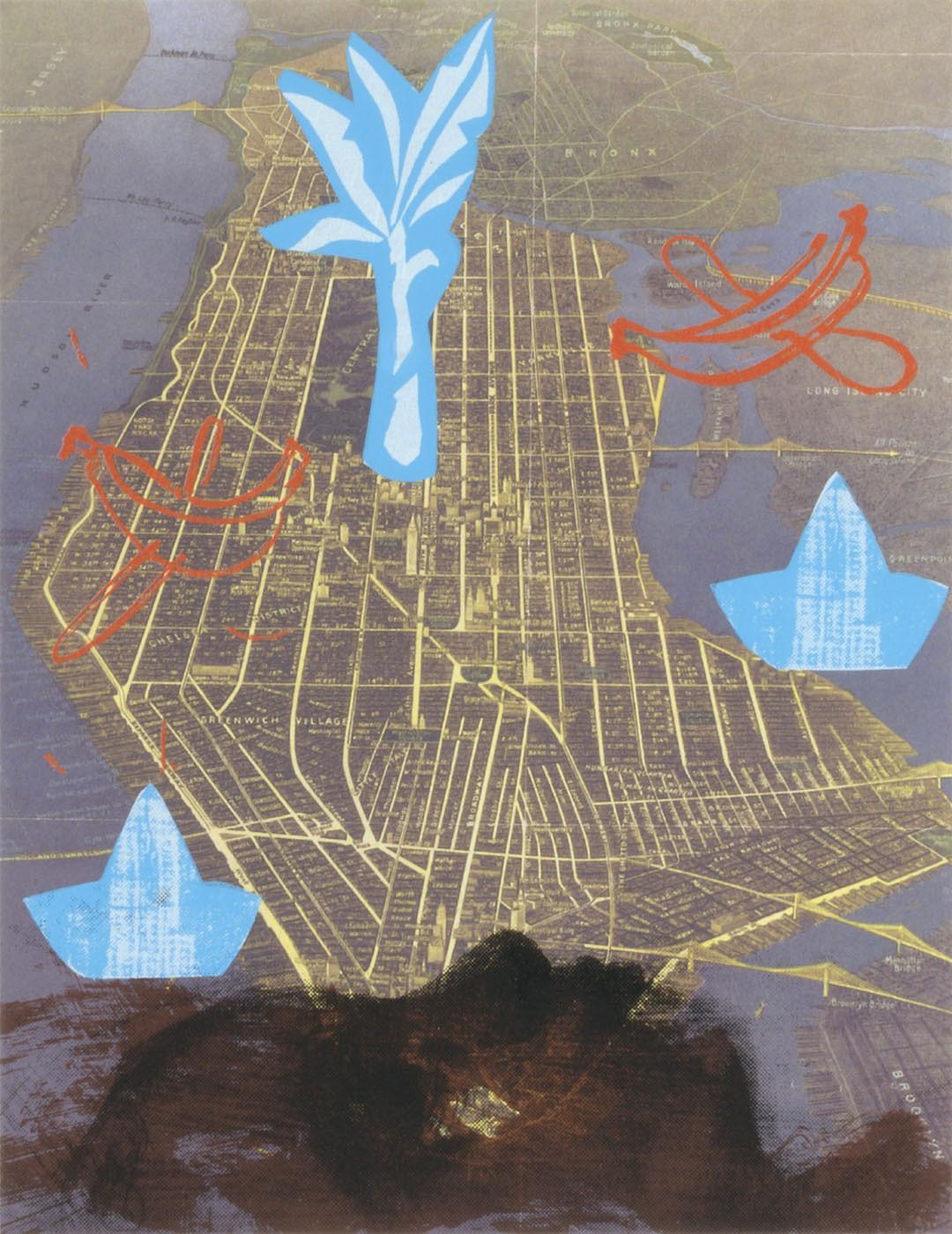

In Scherezade García’s print, Day Dreaming/Soñando despierta, a sleeping figure dreams of two clashing realities: New York City’s urban streets and memories of her homeland culture. The contrasts between the dark background and the lighter floating elements that represent boats, a palm tree, and plantains—a staple fruit in the Dominican Republic—suggest immigrants’ yearning for a life left behind.

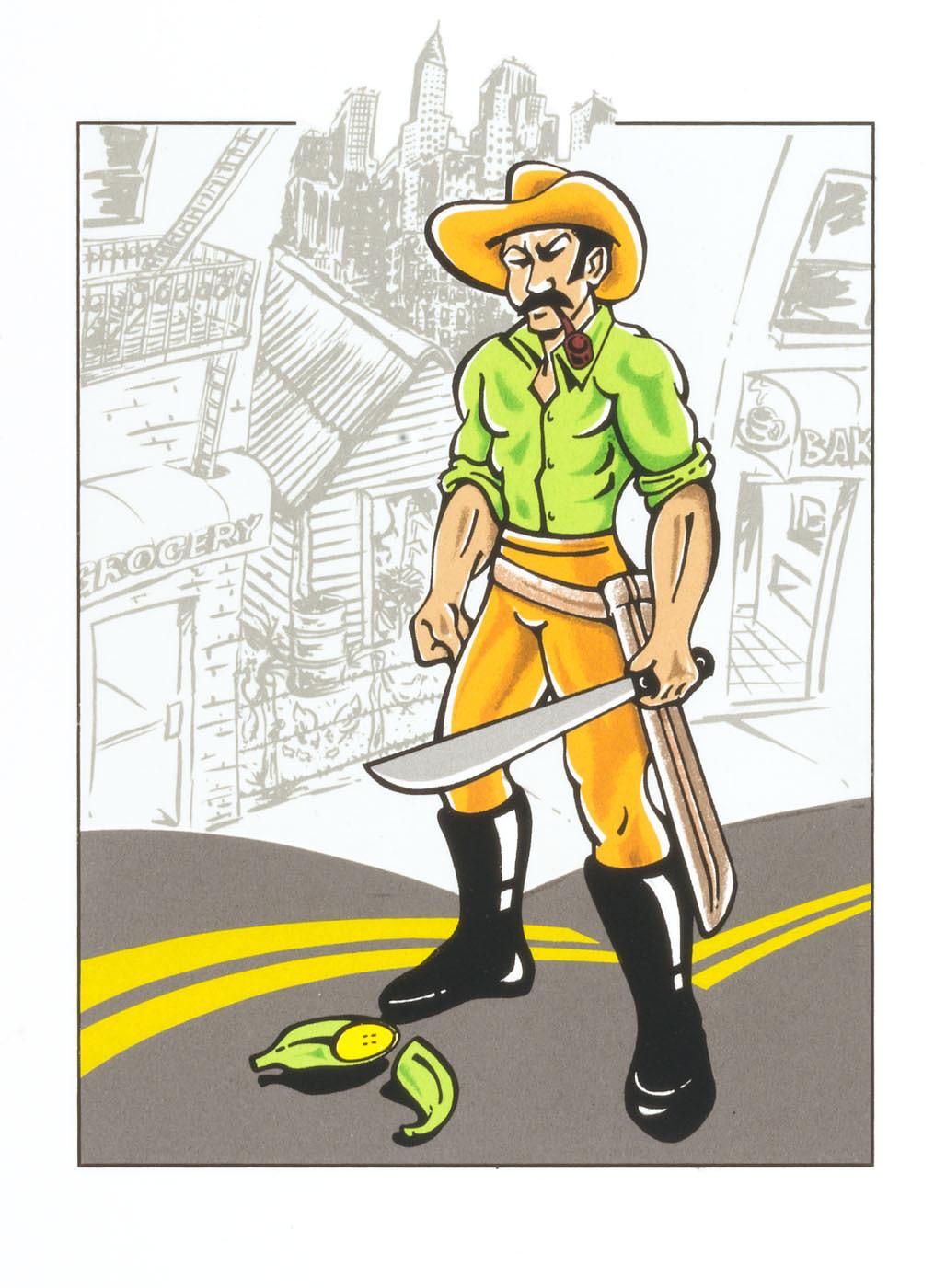

Carlos Almonte’s muscular campesino (farmworker) stands in the middle of a New York City street and affirms his homeland culture in a new context in Vale John. Behind him is a humble Caribbean-styled dwelling transplanted to an urban Latino neighborhood. He holds a machete, a ubiquitous agricultural tool in the Dominican Republic. A plantain, a staple Caribbean crop, appears at his feet.