Tom di Maria is director emeritus of Creative Growth, an organization founded in Oakland, California in 1974 that is a leader in the field of arts and disabilities, advancing the inclusion of artists with developmental disabilities in contemporary art. Judith Scott and Dan Miller are two artists associated with Creative Growth whose work has become an essential part of SAAM's collection. This is the second part of a two-part interview. Read part one.

Howard Kaplan: For people accustomed to society’s dominant methods of communication like the spoken and written word, how does Creative Growth open people's minds to non-traditional communication methods. For example, Dan Miller "has words come out of his hands rather than his mouth," as you are quoted saying in SAAM's We Are Made of Stories exhibition catalogue?

Tom di Maria: When relating to people with disabilities, it’s important not to take an ableist approach. People sometimes ask, “Where's the artist statement?" I haven’t had an intellectual conversation with Dan Miller or Judith Scott, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a statement, or that they aren’t saying anything. I like to point out, ‘All the information is there. You just need to look for it in the art instead of on a text panel. I think we must be open to looking at what's before us, seeing differently. The artist’s statement is embedded in the creative practice and within the art. Are we open to re-learning how to receive and understand it?

Anyone that follows the field of self-taught art is intrigued by this. It's one of the great joys of celebrating an expansive view of art, asking: What is this human quality of creative expression that I'm seeing? This primal voice saying, “I'm an artist.” To me, that's not really mitigated by culture or circumstance, the academy, or intellectualization. If you accept the idea that art distinguishes us from other species—you'll grasp how intrinsic creativity is to the human experience.

We’ve talked about Judith Scott’s process; how does Dan Miller work?

Dan’s process has changed over time. He is on the autism spectrum and largely nonverbal. Sixty years ago, society didn't really know what autism was or how to discuss it, and ways of understanding that spectrum continues to evolve. But when Dan was a child, his family hoped that he would speak and encouraged him by spelling and writing words with him every night. That's how he has language and writing. Those words were going through his head—not just coming out of his mouth. And when he came to the studio, they began to flow through his hands.

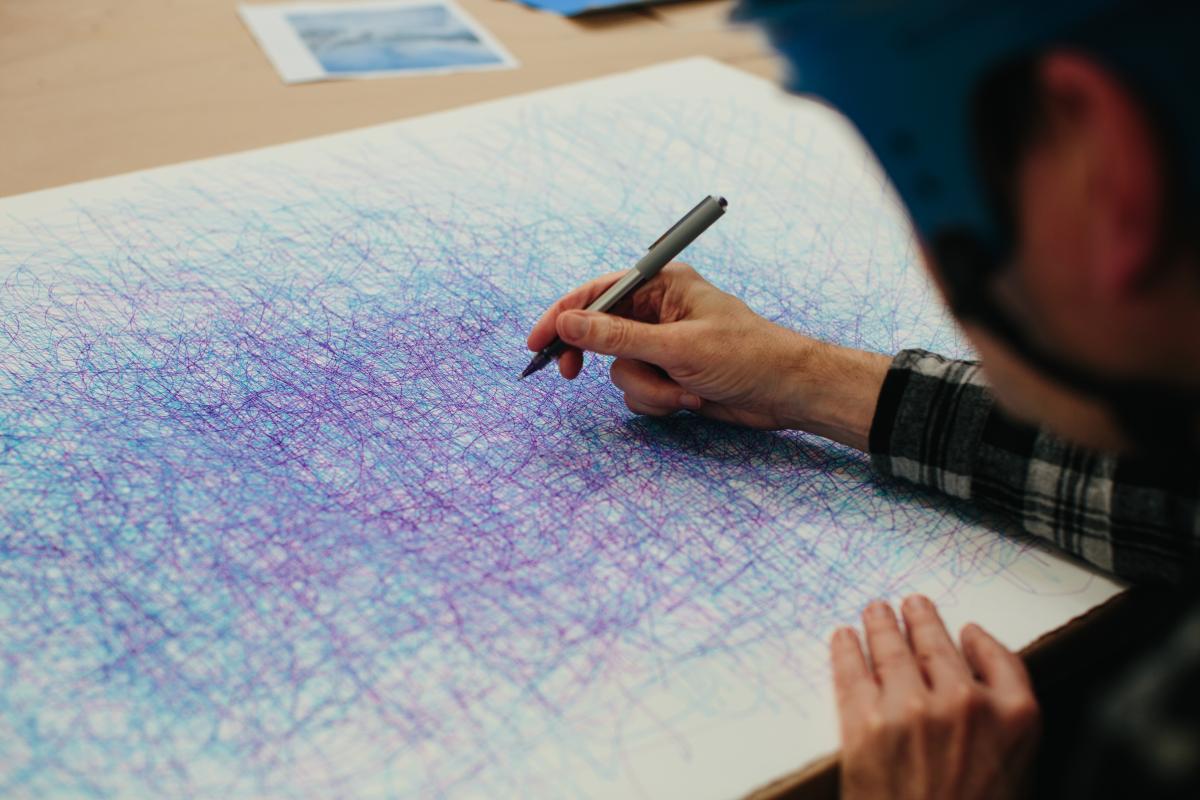

In high school, Dan would scribble on paper and someone--a counselor or his case manager— thought, well, maybe Creative Growth could be a path forward for him. In California, you have a right to public education up to age 21; Dan came when he was 21 and started to write on his drawings. His early drawings were very simple: a light bulb, a cat, a face. And then, some words surrounding a girl’s face (for example), with the name “Jennifer, Jennifer, Jennifer,” who was one of his childhood teachers. Or he’d draw food he liked, such as eggs, and the drawing says “egg.” Then, like most abstract artists, that work became more and more abstract as he progressed over what is now some 30 years of practice. He has always worked flat on a table, obsessively, drawing rapidly. For many years, the work was largely just drawing with ink, in large scribbles, dense tangles of lines, letters, numbers, and words to the point of complete obliteration and abstraction. Then Dan started to add paint. He has experimented with other media too, like ceramics and wood. Primarily, he paints and draws, with access to easels and other ways to make work–other than on a flat surface. It really wasn't 2008 or so, when we had a photographer at Creative Growth who put one of those long rolls of grey backdrop paper up on the wall and Dan walked up to it and drew on it. After that we started to hang paper in those large scrolls right on the wall, and he started to make large-scale work vertically on the wall while standing.

His work became more gestural, of course. Working on a large surface, you have a lot of space to fill and you can move your whole arms when making lines. So now, Dan goes back and forth between doing things seated at a table, and more vertically on the wall.

Are all of Miller’s works language-based or word-based? Looking at SAAM’s collection of his works, all of them are untitled but some of them have parentheses after them, like “Peach and Gray with graphite.” Can you say something about how they are titled?

Yes, Dan’s works are all text based. And if you look at, or follow Dan when he starts a piece, he'll usually say the single word that he's thinking about or writing, for example, “lightbulb, lightbulb, lightbulb;” sometimes it’s clear he is writing that word on the drawing, other times less so. Then usually he'll become interested in the graphic qualities of one of the letters, so the “l” in lightbulbs, for example, will start to be repeated obsessively, smaller and larger, on top of each other, or he'll start to make a gesture that responds to the word. He'll start drawing circles and building things up that way. In the work, probably half the time you can see some letters or text remaining and half the time, it's completely obliterated and we don't know what it was. If the staff artist who is working with him pays attention or makes notes on the words he was saying, we get a sense and we can look at it again and try to see what he was thinking about, or search for those words.

When we give a subtitle to an artwork, we might use color or primary words therein, like “lightbulb.” Today, he's writing his sister's name Cara on a new work. So, it would be helpful for us to refer to it as: "Untitled 2021 (Cara)." Those aren't his titles, but they help us refer to a work, and help viewers find a way into understanding it.

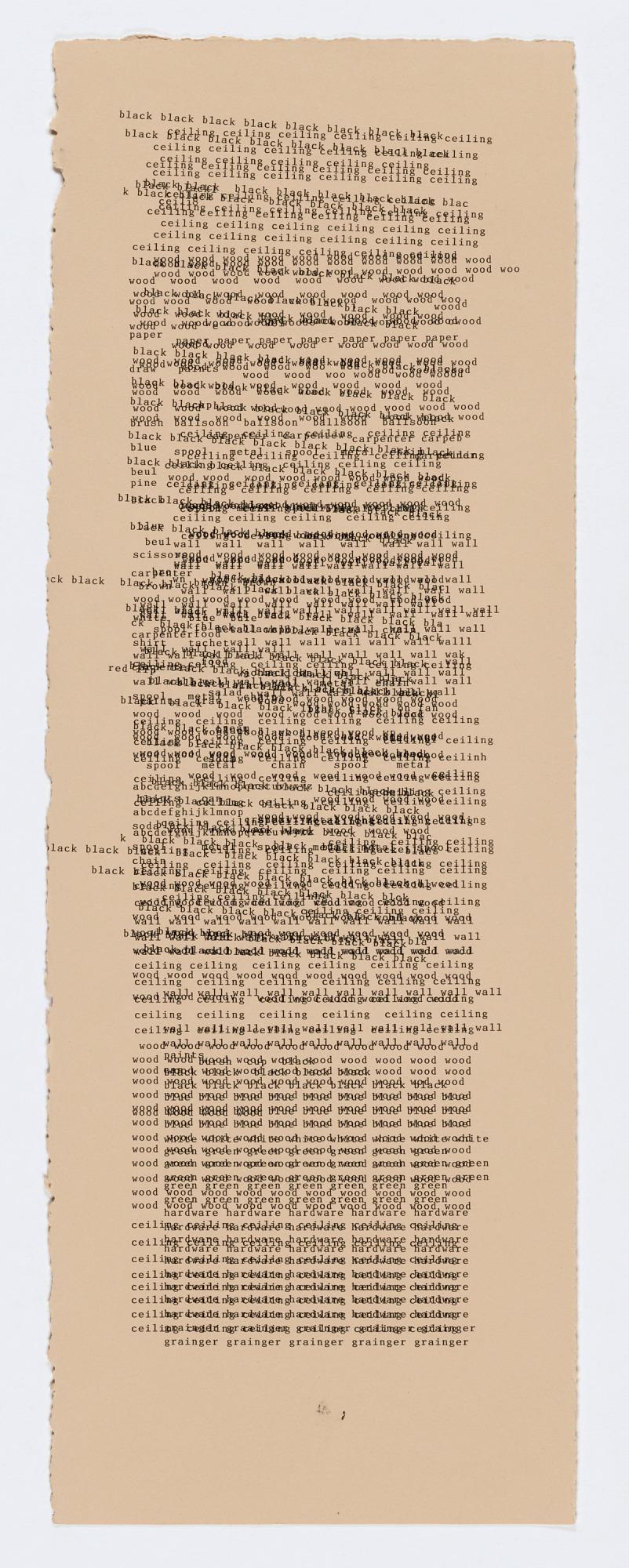

I'm looking at a few of his typewritten works at SAAM; is he adept at using a typewriter? These works are created on paper that is much longer than traditional typing paper and the arrangement of words makes them very interesting.

I think about eight years ago, we had a writing workshop with a visiting artist to encourage many of Creative Growth’s artists to either do journaling or use text; the artist brought journals, pens, magazines, and typewriters. Dan sat at a typewriter typing essentially the same words that he would draw. For a couple of weeks, he stayed at the typewriter, and I thought, “Okay, that's probably the end of his drawing practice.” And to a large extent, his practice has shifted to now include work that he seems to return to in phases. We can't control those things and we don't try to.

If you look at the typed work, it relates very interestingly to concrete poetry and Fluxus work, where he's starting to use the form of the letters and making the same decisions as an abstract artist would make around form and abstraction, order disorder, overlays, constructing and ordering the words in different ways visually. In some ways, the typing works are like Rosetta stones where we're seeing the translation from the drawings and paintings. Often, we can read them more clearly, like “Ah ha”, that's what the hieroglyphic is! It's a paintbrush that he's been writing with all those years, and we didn't know what those words quite were. Sometimes now he’ll hand-write the same word on top of the typing, so you’ll see these combination pieces with both modes together.

How do you view Dan’s legacy?

What's interesting about Dan’s work is that it is very contemporary looking. Of course, you can approach it and say, “Oh, I want that over the couch,” but the context in which it was made, who the artist is—those factors ask you to approach it in a more sophisticated way.

For me, Dan's work is extremely impactful. If you look at visual materials, there's often this tension between the content--what it's about, the form, how it looks--and for Dan, the content and the form are one and the same. So, it forms this integration of language and aesthetics, meaning and visual presentation, all so intrinsically linked that you can't have one without the other. It just feels very complete.

Do other artists at Creative Growth see Miller as a mentor?

As previously mentioned with Judith Scott, Miller also is seen as a hero and a practitioner He has created a specific powerful art practice without ableist intervention in a language and style of his own making. In this way he is an inspiration for others on the autism spectrum, but also for artists seeking their own voice.

We give tours and if a family comes with teenagers or kids on the spectrum because they're looking for opportunity, for community, or to see what it means to live with autism. They'll come to know Dan personally and look at him and show him as a role model. He demonstrates that one can be on the spectrum and have work in MoMA and in the Venice Biennale; those kinds of opportunities didn't exist before, and indeed Dan is a role model, a recognized contemporary artist and a human being in the 21st century with so much to say to all of us.