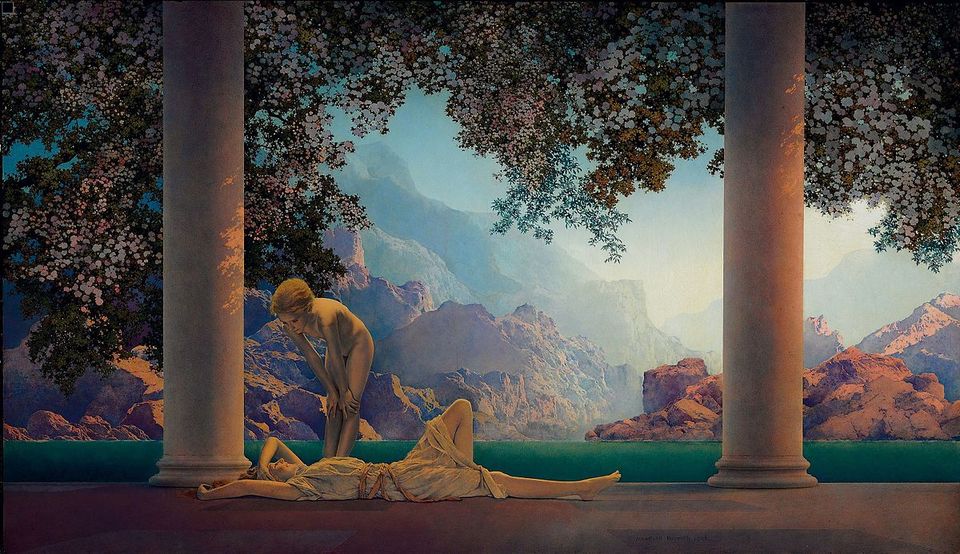

Maxfield Parrish, Daybreak. 1922

In your hurry to cut out of work early before Memorial Day, fill up the cooler, and head toward sunnier climes, you might have missed the news about the rather extraordinary sale of Maxfield Parrish’s Daybreak at Christie’s Important American Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture auction. It was a whale of a sale for a painting of any sort, but the fact that Daybreak was originally commissioned to be a template for commercial reproductions puts Parrish in an elite company of commercial artists who capture mass appeal and manage nevertheless to stake a claim in the critical and curatorial landscape. Art Daily reports:

The most popular American illustrator after World War I, Parrish was commissioned to paint Daybreak by the art publishing firm, House of Art, in August 1920. The painting was his first work commissioned solely for the purpose of reproduction as a color lithographic print to be distributed to the American public—and it became one of the most reproduced paintings in American history. At the height of its popularity, it was estimated one of every four households had a copy, making it a national sensation and cultural phenomenon.

In his own time, Parrish was not considered to be a fine or high artist; critical and curatorial interest in his work surfaced long after the fact. As you sometimes find with commercial design, a secondary fascination emerges later on independent of the product itself—consider collectors of album cover art or pulp-fiction covers. Those kinds of illustration (and others that immediately come to mind) are sold and traded as kitsch.

But rarely are commercial illustrators elevated to the highest-selling sphere of artists. A colleague of mine attributes a recent rise in critical interest in Parrish’s work—which persists, though not widely, among critics and curators—to Sylvia Yount’s exhibition of Parrish’s paintings at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art in the 1990s. In 1964, then-Guggenheim director Lawrence Alloy first revived the artist’s painting, exhibiting his work as a precursor to Pop art. (Hence Parrish’s nickname, “Grand-Pop.”)

Parrish’s Christie’s appearance puts him in the company of beloved artists like Childe Hassam, Norman Rockwell, and Andrew Wyeth, all of whose precarious standings among some art-world rainmakers persist nevertheless. Parrish himself didn’t shy away from the question of whether his own work was more than kitsch: “There are countless artists whose shoes I am not worthy to polish whose prints would not pay the printer. The question of judgment is a puzzling one.”