In "Dance With Duality," her essay for Joseph Cornell: Shadowplay Eterniday, Linda Roscoe Hartigan writes:

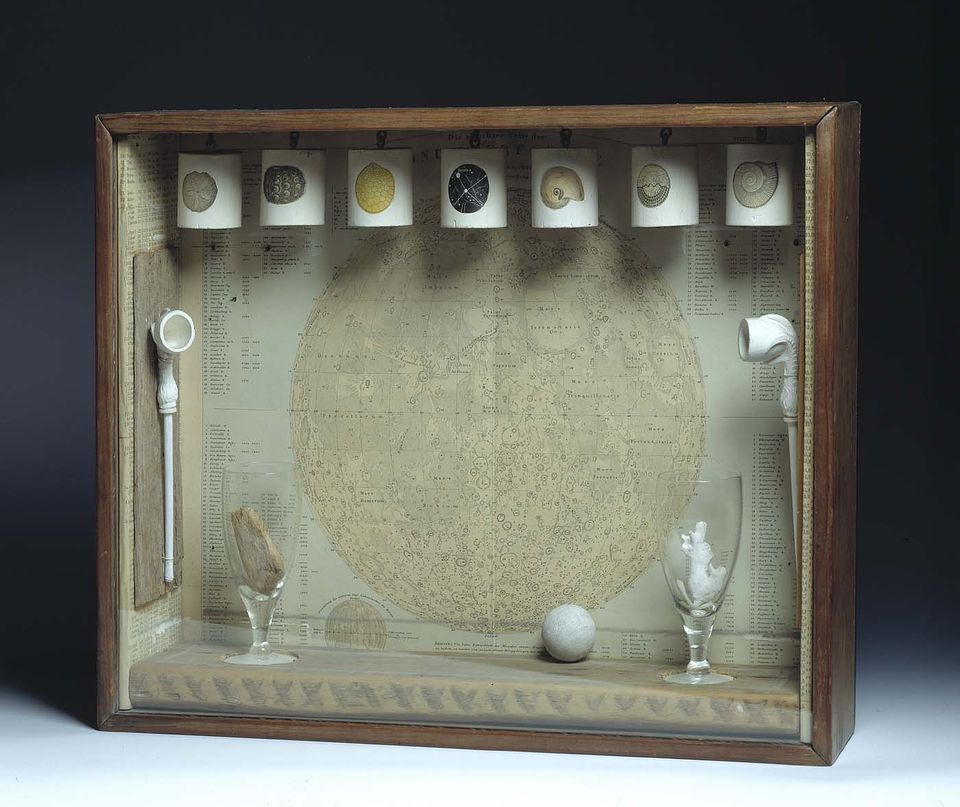

Excess is not usually associated with an artist whose lifestyle has been characterized as ascetic and whose art is contained on an intimate scale. Yet Cornell indeed engaged in marvelous excess. Just imagine the contents of his tiny house at the time of his death: easily three thousand books and magazines, a comparable number of record albums and vintage films, enough diaries and letters to now fill more than thirty reels of microfilm, and tens of thousands of examples of ephemera—from postage stamps to clay pipes, from theatrical handbills to birds' nests. Cornell surrounded himself with volumes of stuff, telling proof that he had absorbed the horror vacuii—or fear of empty spaces—associated with the design sensibility of the Victorian era in which his family lived.

She goes on to speculate about the degree to which his upbringing and personal fortunes affected the artist, going so far as to wonder whether Cornell was obsessive-compulsive in s clinical sense. (It would hardly be a negative judgment if Hartigan believed that to be the case: She calls his acquisitiveness "evidence of a peripatetic intelligence and capacity for inclusiveness.")

Cornell the man is an amalgamation of Laura and Tom Wingfield, the misérables from Tennessee Williams's The Glass Menagerie. Like Laura, Cornell was afflicted by a nearly debilitating bashfulness, and turned his attention to precious objects; like Tom, Cornell was charged with the care of a sick sibling (his brother, Robert, had cerebral palsy).

As you read further in Hartigan's essay, she zeros in on accumulation as an artistic strategy, making an acute observation:

How did Cornell make sense out of accumulation? The desire to evaluate, differentiate, arrange, and cross reference is a fundamental aspect of human intelligence, and, in Cornell's case, also an offshoot of his appreciation of science as a means of understanding and ordering existence. Like a scientist equipped with specimens and field notes, he was strongly oriented toward cataloguing—classifying descriptively—and taxonomy—classifying according to relationships.

This isn't merely a neat aspect of his work or personality — it was necessary for dealing with his vast collection of found things, if not for assembling it in the first place. His scientific bent puts him in a league with naturalists like Audubon, the artist who exemplifies the empirical instinct in American art in Adam Gopnik's estimation. It's a simple thing to understand that Cornell collected a lot of stuff for his works, but you can't help but want to see Cornell's vast materials archive when you see them (a great many of which are now on display at American Art).

Related Link: A SAAM slide show of works from Joseph Cornell: Navigating the Imagination.