To fully reveal Cornell's boxes, traditional gallery lighting above the cases was supplemented with small lamps hidden behind the case labels, which illuminated the objects from below.

We asked SAAM's lighting designer, Scott Rosenfeld, to discuss his thinking as he lit the exhibition on Joseph Cornell currently on view in the third-floor galleries.

“Why should I care?” This is the question that typically pops into my head before I design the lighting for an artwork. I figure I need to know why an artwork is compelling before I can--quite literally--see it in the proper light. So I begin a project by staring at the art for a while, getting input from curators, exhibit designers, and conservators. Then, after I understand a bit about the work, I go about my business of actually hanging the lights. Our first goal is always visibility, but the answers to that initial question, “Why should I care?” are always central to how we make the artworks visible. At the end of a good day not only are the artworks appropriately lit, but the light actually assists in the communication between what the artist is offering and what our visitors receive.

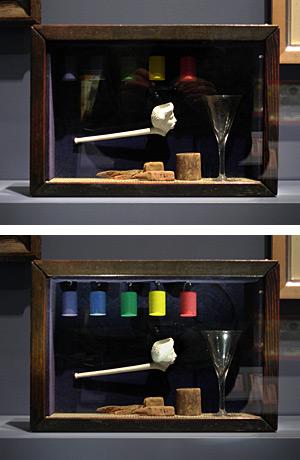

Designing the lighting for SAAM’s Joseph Cornell retrospective (QTVR, Quicktime) is a good example of this process. For one thing, lighting a Cornell box so it’s clearly seen is a challenge in itself. The materials Cornell used are light sensitive (so the light has to be dim) and his glass-covered boxes are reflective, with deep recesses chock-full of information. Our standard method of lighting (track lights from above) does a good job revealing the lower portions of the boxes. But light aimed from the ceiling can’t penetrate the tops of most boxes; the deep recesses are lost in shadow.

To solve this problem, Evi Oehler, SAAM's head of exhibit design, and I designed casework in which tiny fiber-optic fixtures were hidden under each label panel. Two-thirds of the lighting is still from those ceiling mounted tracks, but these tiny lamps (actually scaled-down versions of theatrical fixtures) allowed us to sneak light up into the top third of each box. Between the track lights above and the fiber optics below, we created a very flexible system that even allowed us to control where the shadows would land.

So with this lighting system in hand, our primary goal of visibility was accomplished, and for many boxes answers to the “Why should I care” question became apparent as Cornell’s world of story, poetry, and atmosphere came into view. In Soap Bubble Set: Object, for example, fixtures aimed from below revealed colorful cylinders, while in Medici Prince: Object the Prince’s face would have disappeared without the lights hidden below the label rail.

Curator Lynda Hartigan’s guidance was crucial in helping me decipher what Cornell was trying to communicate so the lighting choices could support the artist's intent. For example Untitled (Grand Hôtel de l’Observatoire) is a box that tells the story of Andromeda being released by Zeus into the heavens. The actual meaning of the artwork changes depending on where a shadow is cast from a chain hung in the center of the box. Before I knew the story of Andromeda my first impulse was to place the chain's shadow to the right of Andromeda so she was struggling to reach for it (wrong answer!). I then tried placing the chain's shadow in Andromeda’s hand, which also didn't work. We finally settled on placing the shadow at the tip of Andromeda’s fingers to support the idea that she is being released from bondage. In each of these cases we had to carefully line up the lights above and below so they formed a single cast shadow.

Cornell himself used light beautifully to draw us deeper into the worlds of his boxes. Untitled (Owl Habitat) is almost totally dark without the light Cornell built into the box, and in Renée Jeanmaire in "La Belle au Bois Dormant" a dancer appears from darkness when the box is internally illuminated. In Untitled (Great Horned Owl with Full Moon), Cornell provides the opportunity for us to backlight the moon through a translucent screen to create a rich atmosphere with great depth.