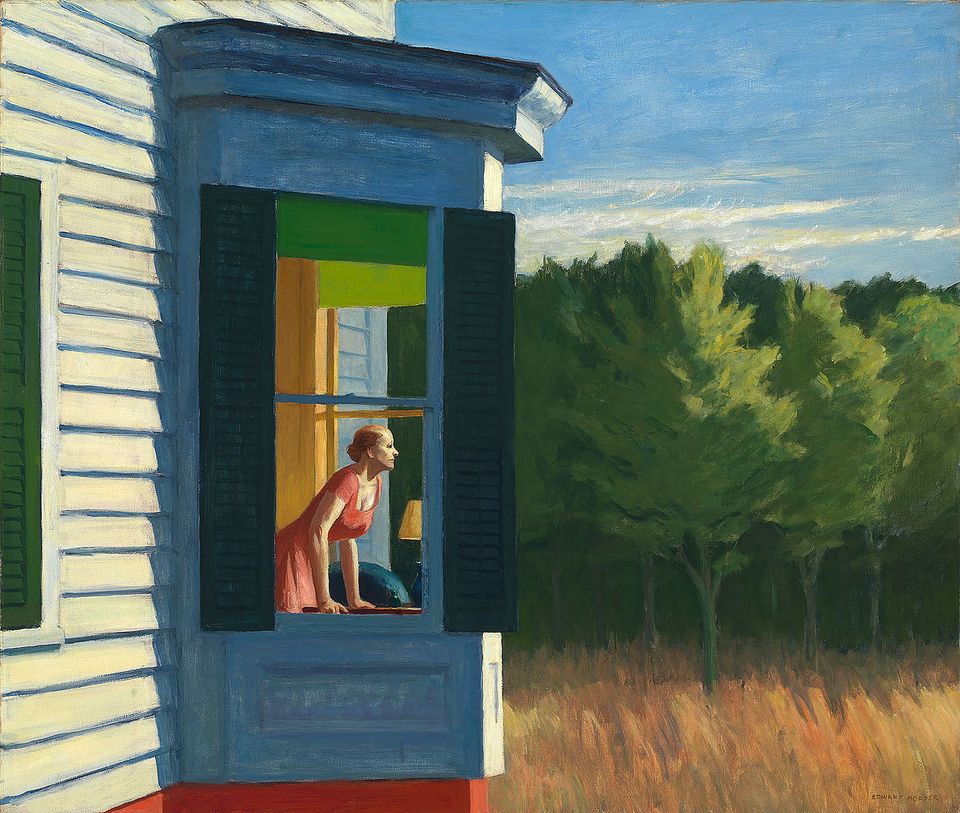

In honor of the 136th anniversary of Edward Hopper's birth, we're taking a closer look at his iconic painting, “Cape Cod Morning,” one of the highlight's of SAAM's collection.

In Cape Cod Morning, a woman looks out a bay window at something in the middle distance, something just beyond the frame. The window, cast in deep shadows, juts out from a facade bathed in brilliant light. Here, half the composition is given over to a richly hued, golden grass landscape, one tethered only by undulating clouds. A strain reverberates throughout the piece, situated everywhere and nowhere in particular. This inherent tension has come to define much of Edward Hopper’s work, but to probe it deeply, as observers are wont to do, is to miss the artist’s subtleties, his splendor.

Born July 22, 1882 in Nyack, New York, Hopper, from an early age, gravitated to solitary pursuits, among them, sketching and sailing, studying with intention the nuances of light and shadow. The artist, who would go on to produce more than 800 paintings, watercolors, and prints, remained a detached observer of the world. Writing in The Guardian, Laura Cumming echoes this: “‘one was aware,’ wrote a friend, ‘of a slight displacement in [Hopper’s] experience of his own person…as when we are strangers to ourselves, and become objects of our own contemplation.’” Implicit in this is a worldview that privileges the literal over the metaphorical. It follows, then, that imposing too lofty a narrative, or any narrative, for that matter, on Hopper’s works, is to do his carefully constructed oeuvre a disservice.

Venturing cautiously in interpreting work like Hopper’s proves particularly useful as paintings like Cape Cod Morning obscure as much as they reveal. In an essay for The New York Review of Books, Mark Strand writes that, in Hopper’s hands, “moments of the real world, the one we all experience, seem mysteriously taken out of time. The way the world glimpsed in passing from a train, say, or a car, will reveal a piece of a narrative whose completion we may or may not attempt.” What this view of the artist’s work obfuscates, though, is the meticulous construction of works like Cape Cod Morning. Indeed, Hopper himself attested to the careful execution of these works, an intention that involved as much elaboration as it did observation. In Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography, Gail Levin writes that the artist sought “the esthetic confluence of that ‘something inside me and something outside…to personalize the rainpipe.'”

Of the woman in Cape Cod Morning, too, reality is so abstracted as to present not a woman gazing out the window, but a figure gracefully removed from the world. Indeed, Strand asserts that “the women in Hopper’s rooms do not have a future or a past. They have come into existence with the rooms we see them in.” To assign too personal a meaning to any of these figures, then, is to belie their staged, cinematic like, construction.

Perhaps, as evidenced in Cape Cod Morning, as it is in a great many Hopper works, the ambiguity of these paintings is their very strength. In his 2012 Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Clarice Smith Distinguished Lecture in American Art, Kevin Salatino asserted that “when [Hopper] is cryptic, he is cryptic in the most interesting way.” To be sure, the artist’s masterful ability to render the momentary, or seemingly momentary, is a talent that is unmistakably his. The task, then, is to dispense with ad hoc narratives and to appreciate in Cape Cod Morning the subtle play of light on the wall, deceptively discrete as it might be.