A recent Terra Foundation Predoctoral Fellow in American Art at SAAM, Clarisse Fava-Piz is completing her dissertation, ‘Sculpting Beyond Borders: Local Identity and Transnational Mobility in the Age of Rodin,’ at the University of Pittsburgh. This blog post is based on a talk Fava-Piz gave at SAAM as part of the Art Bites series.

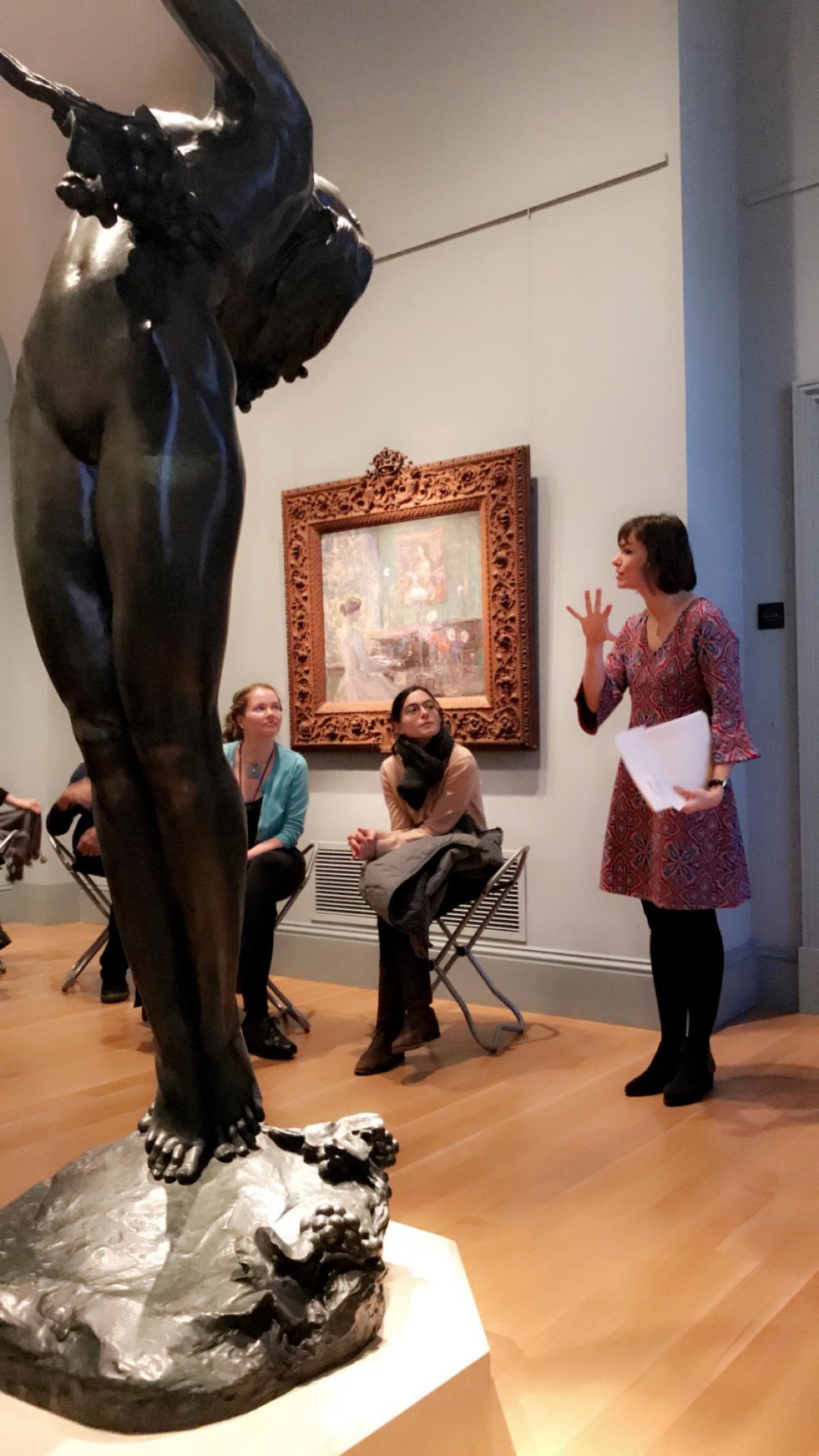

Peeking into the second-floor side galleries, visitors cannot help but notice a life-size female figure standing on the balls of her feet, projecting her body forward, her head held dramatically backwards, all the while in perfect balance, and how she activates the space around her. Her only prop is a vine that flows from her left fingernails to her right hand wrapped behind her head. Her nude body is athletic and strong, although she looks as pliant as the vine. From afar, her body draws a curve, a single line that runs from her feet, well-anchored in the ground, to the top of her head, emphasizing her elongated jaw. This sculpture captures a fleeting action that seems quite natural at first, but, is it really? What does this work tell us about the sculpted body, and its relationship with other forms of modern art, such as dance?

To answer these questions, any art historian of sculpture would suggest that you start with the pose. During my talk, our entire group of more than two-dozen people stood up, and attempted to recreate the posture with their body—who said that sculpture wasn’t fun?! We quickly learned that although she is holding a vine, the symbol of Bacchus, the Greek god of excess and euphoria, this young woman could not be intoxicated. Her posture requires a great command of the body, controlled and steady, solid as the material of the bronze itself suggests. Indeed, the American sculptor who conceived this piece, Harriet Whitney Frishmuth (1880-1980), was known for working with professional dancers, who could hold difficult poses at length.

A well-traveled artist, Frishmuth had studied sculpture in Paris under French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) in the early 1900s, at a time when sculptors were particularly inspired by new forms of choreography. Desha Delteil, the model who posed for The Vine, was a dancer with the Fokine Ballet, created in 1913, with the goal of liberating the body from the academic conventions of the traditional ballet practice where the emphasis of the movement was restricted to the lower body. Photographs by Arnold Genthe housed in the Library of Congress, show Desha Delteil holding the pose as in The Vine, although she is not using any props here.

Conceived first as a statuette in Frishmuth’s studio in New York City, The Vine became the artist's most commercially successful work, with an edition of 396 casts. It was only in 1923, for the ‘Exhibition of American Sculpture’ organized by the National Sculpture Society’s celebration of its thirtieth anniversary, that Frishmuth enlarged The Vine. That same year, the National Academy of Design awarded it the Julia A. Shaw Memorial Prize for the best work by an American woman. Five editions of the large Vine were cast; four of the five are in museum collections.

I find it particularly apropos to look at Frishmuth’s The Vine as we approach the hundredth anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 2020. Some scholars interpret Frishmuth’s The Vine, created in 1923, only a few years after women were given the right to vote, as a symbol of political and social freedom during the era of Prohibition.