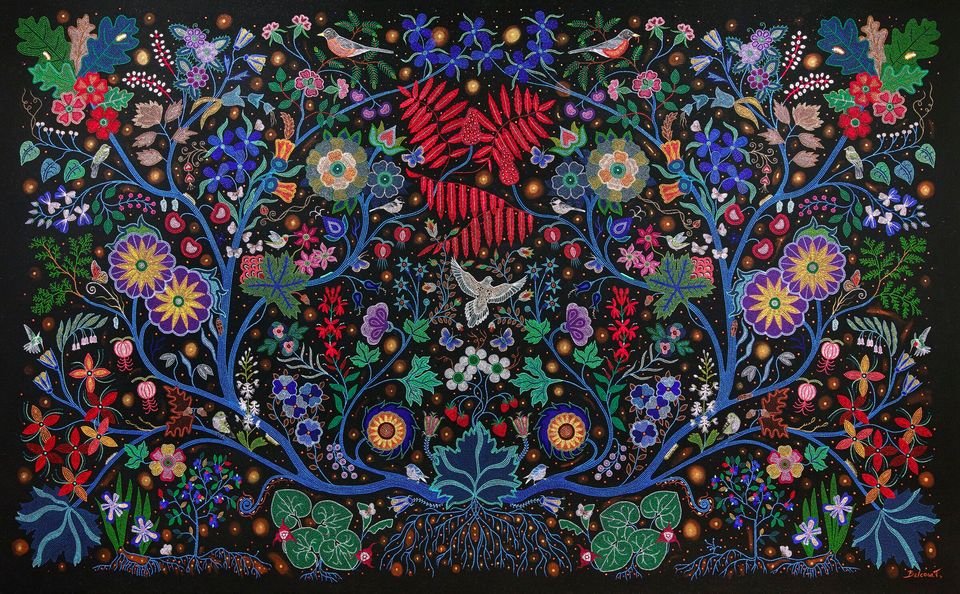

Christi Belcourt (Michif), The Wisdom of the Universe, 2014, acrylic on canvas, Collection Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; Purchased with funds donated by Greg Latremoille, 2014, 2014/6. © Christi Belcourt

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, opens at the Smithsonian American Art Museum's Renwick Gallery on February 21, 2020. The Renwick is the third stop on a national tour for this groundbreaking, eye opening exhibition. It is the first major thematic show to explore the artistic achievements of Native women. The presentation at the Renwick includes more than 80 artworks dating from antiquity to the present, made in a variety of media from textiles and beadwork, to sculpture, time-based media and photography. At the core of this exhibition is a firm belief in the power of the collaborative process. In 2015, exhibition curators Jill Ahlberg Yohe and Teri Greeves (Kiowa Nation) formed the Native Exhibition Advisory Board—a panel of 21 Native artists and Native and non-Native scholars from across North America—to provide insights from a wide range of nations at every step in the curatorial process.This story was originally published May 31, 2019 on the blog of the Minneapolis Institute of Art. It has been edited for clarity.

I am the co-curator of the exhibition, along with Jill Ahlberg Yohe, associate curator of Native American Art at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. I am an enrolled Kiowa currently living in Santa Fe, New Mexico. My family allotments are in the Hog Creek area around Anadarko, Oklahoma. My grandmother is/was Suzy Ataumbi Big Eagle and we are descendants of Two Hatchet. My mother is/was Jeri Ah-be-hill, and she raised my sister (Keri Ataumbi) and I among the Eastern Shoshone in Fort Washakie, Wyoming, on the Wind River Reservation. My mother had a trading post on that reservation for over 20 years and once she divorced my dad, a non-Indian, we moved to Santa Fe and she started over, selling Native American art from up north to a tourist audience visiting the Southwest.

When Jill approached me about the exhibition, around five years ago, the very first thing I requested was a large advisory board. I am aware that I have no rights to talk about other tribes’ things—I barely have any rights to speak of Kiowa things, as I am not an elder. And I know that the white-man world does not see things the way Native people do, so it was very important to me that we assemble as many women advisors from around North America as we could.

Jill agreed, and worked hard to get nearly two dozen Native women to sign on (their names and affiliations are below), along with a few non-Native advisors. While certainly not representative of all Native Nations, they are respected artists and academics from their communities. We asked for their help throughout the entire exhibition process—not just once during a meeting at the museum—and they very generously shared their knowledge. They helped us develop our themes at that first big meeting, and once Jill and I made it into a tighter outline, we emailed it back to all of them for their input. We asked them for the most important women artists or pieces of works that they knew about—the works they felt should be included—and we included them.

Dakota Hoska, research assistant at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, created massive Dropbox folders with images of everything we saw on the road while looking at possible works to include, and we sent links to these images to our advisors, so they could offer their input on them. Once we developed a checklist—a summary of all the objects we wanted to include—we sent this to the advisors as well, and they helped us understand where we had over-represented or under-represented some works, peoples, time periods, and mediums.

We also called upon these women to write essays in the catalogue for the exhibition, so that multiple Native voices could be heard from different Native perspectives. Finally, we invited all of our advisors to come to Minneapolis for the opening, and to speak on panel discussions about the exhibition. Hearts of Our People would not exist without all of these women’s voices.

In this exhibition, we wanted to honor all of the Native women—past, present, and future—who have created our worlds. It is a tall task, and I’m sure there are things we could have done better or differently. We also did not walk into this exhibition with the idea that it was going to be a definitive or complete “study” of Native women’s art. That would be impossible. But we are hoping that it will start conversations, and by having a larger presence in the fine arts world at its four venues including the Renwick Gallery, the influence of all of our Native women on the traditional canons of the art world will not be ignored anymore. With that said, as a traditionally minded person, I know that our women do not need the validation of the “Western art world” to continue to create those worlds for which we, as Native people, were born for. It is my prayer, however, to get the rest of the world to understand the power of creation that we know and feel from our grandmothers, mothers, aunties, and sisters.

Thank you to the Native Exhibition Advisory Board formed in 2015 to consult on the creation of “Hearts of Our People.” They include:

heather ahtone, Choctaw/Chickasaw, senior curator, American Indian Cultural Center and Museum, Oklahoma City; DY Begay, Navajo artist, Santa Fe; Janet Berlo, professor of Art History and Visual and Cultural Studies, University of Rochester; Susan Billy, Pomo artist, Ukiah, California; Katie Bunn-Marcuse, director and managing editor, Bill Holm Center for the Study of Northwest Coast Art, Burke Museum, Seattle; Christina Burke, curator, Native American and Non-Western Art, Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa; Kelly Church, Anishinaabe artist and educator, Michigan; Nadia Jackinsky, Alutiiq art historian, Anchorage; Heid Erdrich, Ojibwe writer and curator, Minneapolis; Anita Fields, Osage artist, Tulsa; Adriana Greci Green, curator, Indigenous Arts of the Americas, The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia; Carla Hemlock, Mohawk artist, Kahnewake; America Meredith, Cherokee, publishing editor of First American Art Magazine, Oklahoma City; Nora Naranjo Morse, Santa Clara artist; Cherish Parrish, Anishinaabe artist and educator, University of Michigan; Ruth Phillips, Canada Research Professor and Professor of Art History, Carleton University; Jolene K. Rickard, Tuscarora, artist and Associate Professor, The Department of the History of Art and Visual Studies, Cornell University; Lisa Telford, Haida artist, Seattle; Graci Horne, Dakhóta, independent curator, Minneapolis; and Dyani White Hawk, Lakȟóta artist and curator, Minneapolis.

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists is on view in Washington, DC from February 21 through May 17, 2020.