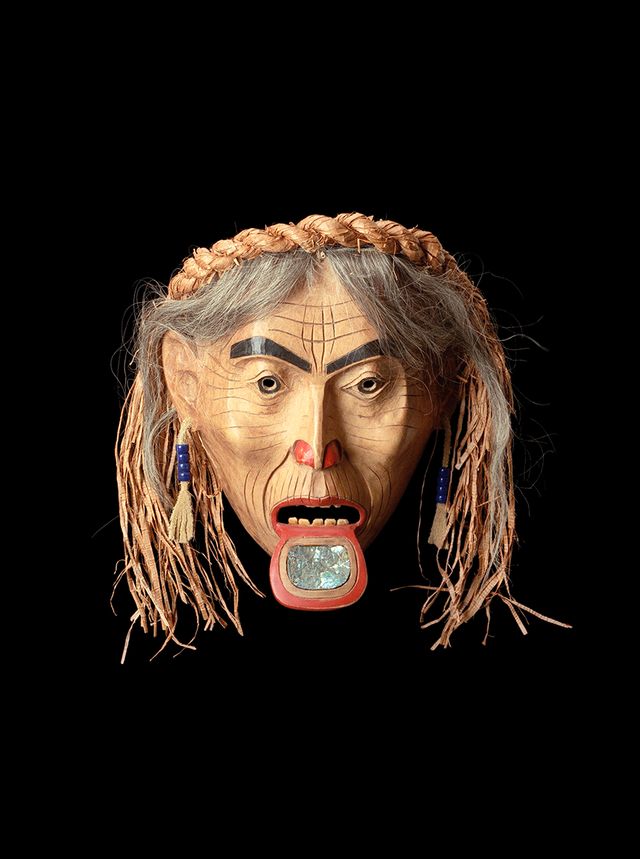

The Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists exhibition is multilingual with descriptive text presented in both the artist’s Native American or First Nations languages, as well as English, aiming to present the works in the context of each artist’s own culture and voice.

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists

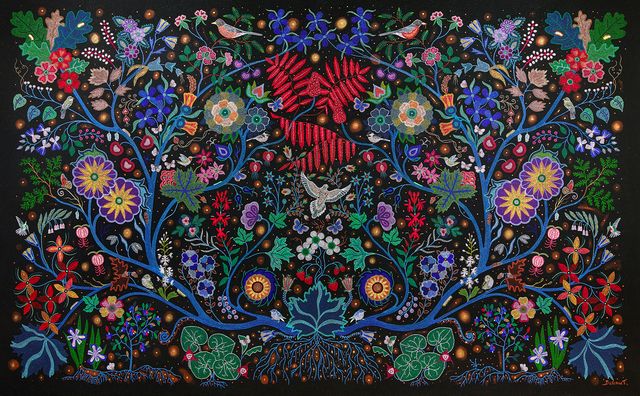

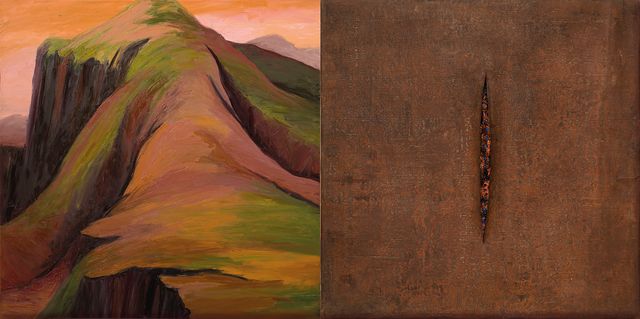

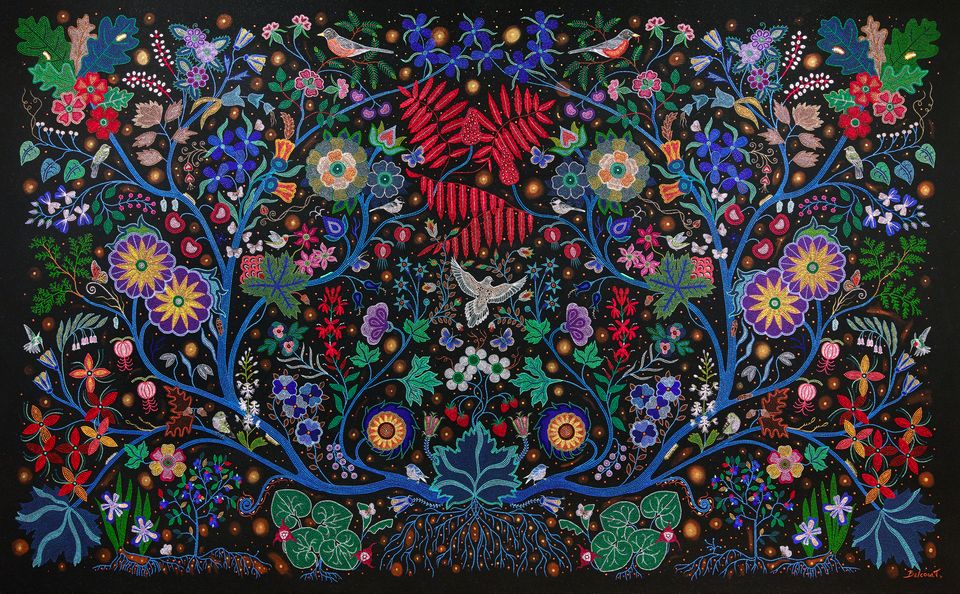

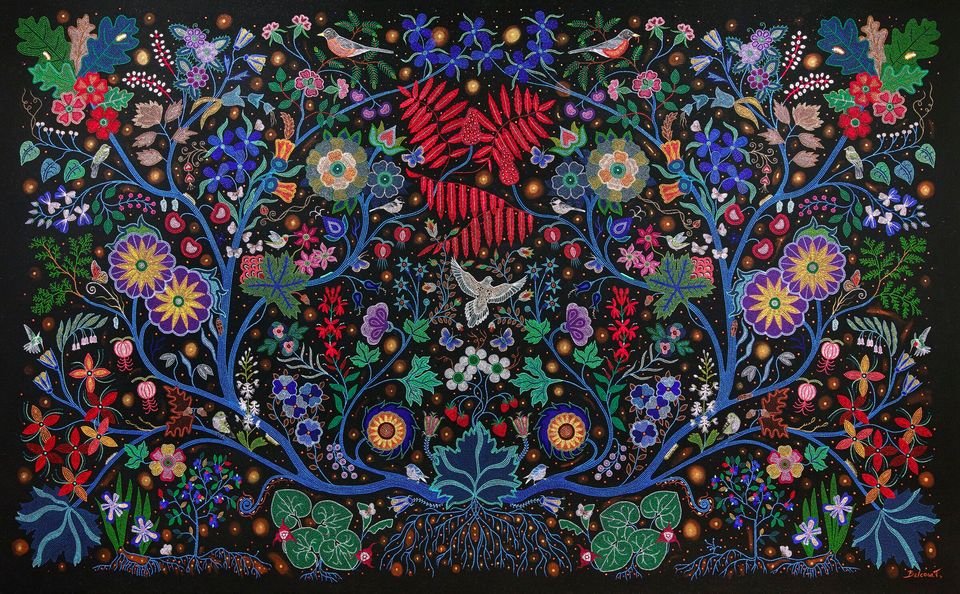

Christi Belcourt (Métis),The Wisdom of the Universe, 2014, acrylic on canvas; Art Gallery Ontario, Toronto; Purchased with funds donated by Greg Latremoille © Christi Belcourt

“At long, long last, after centuries of erasure, Hearts of Our People celebrates the fiercely loving genius of Indigenous women. Sumptuous, gorgeous, eternal, strange, this art is alive. Be prepared for an encounter with power and joy!”

—Louise Erdrich, author

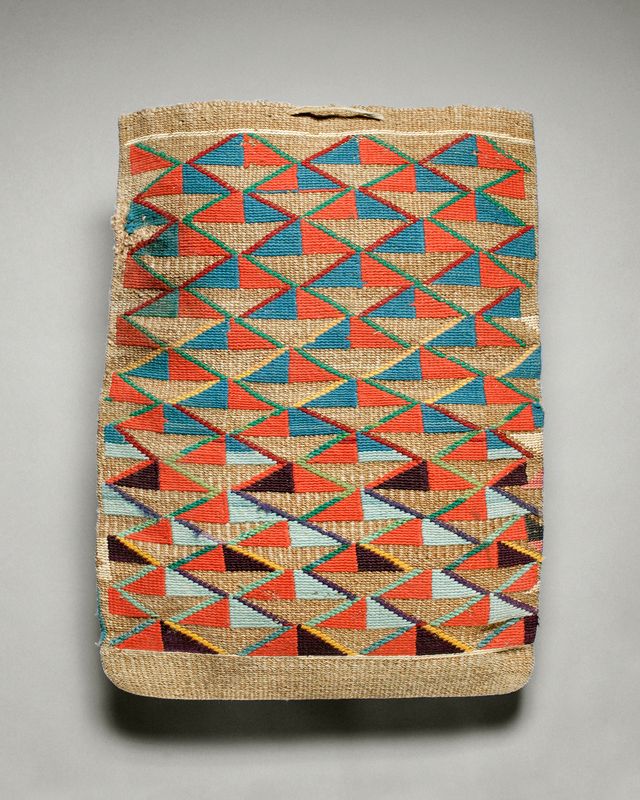

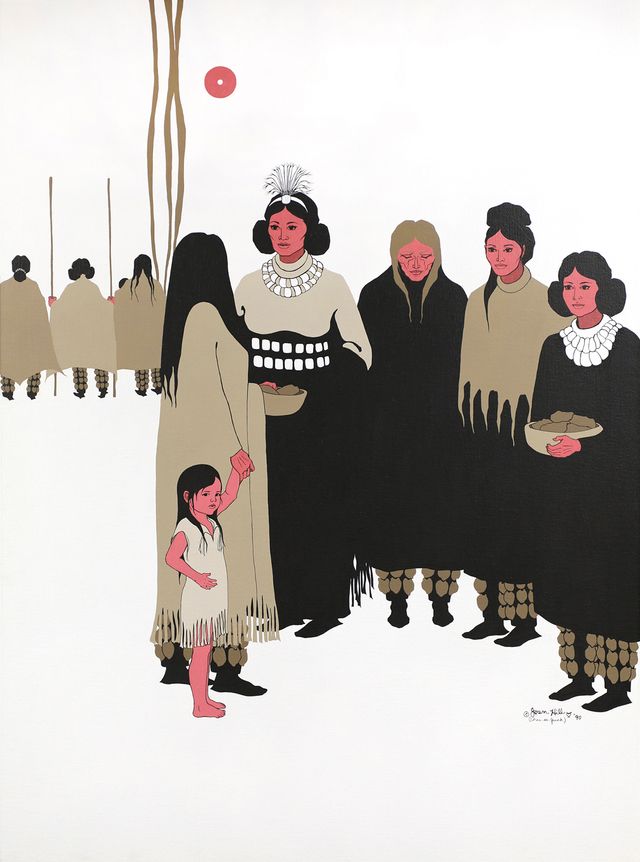

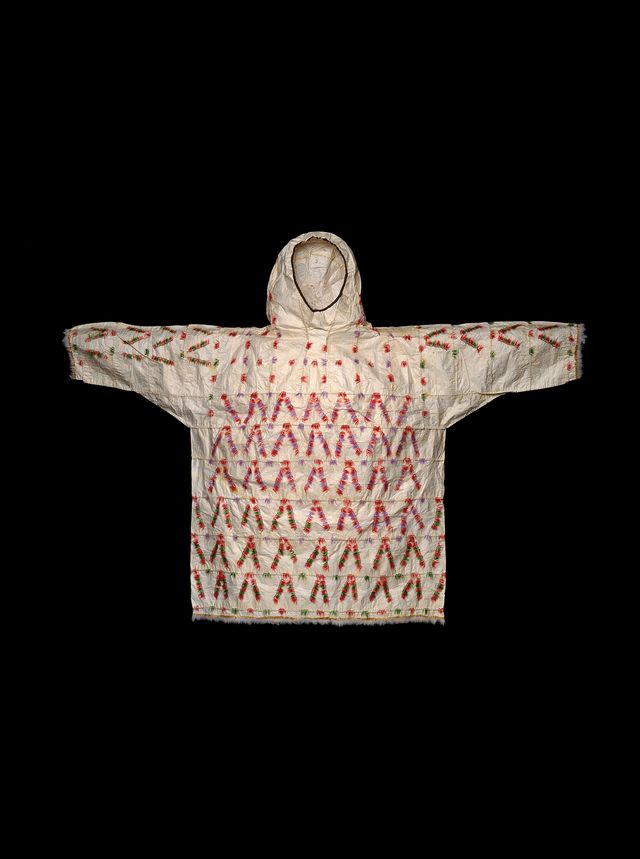

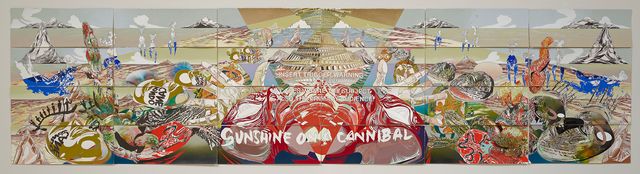

Women have long been the creative force behind Native American art, yet their individual contributions have been largely unrecognized, instead treated as anonymous representations of entire cultures. Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists explores the artistic achievements of Native women and establishes their rightful place in the art world.

Description

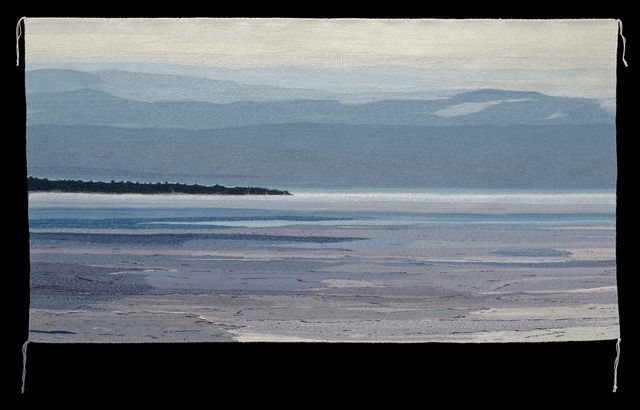

This landmark exhibition is the first major thematic show to explore the artistic achievements of Native women. Its presentation at SAAM’s Renwick Gallery includes 82 artworks dating from antiquity to the present, made in a variety of media from textiles and beadwork, to sculpture, time-based media and photography. At the core of this exhibition is a firm belief in the power of the collaborative process. A group of exceptional Native women artists, curators, and Native art historians have come together to generate new interpretations and scholarship of this art and their makers, offering multiple points of view and perspectives to enhance and deepen understanding of the ingenuity and innovation that have always been foundational to the art of Native women.

The exhibition is organized by Jill Ahlberg Yohe, associate curator of Native American Art at the Minneapolis Institute of Art and Teri Greeves, an independent curator and member of the Kiowa Nation. An advisory panel of Native women artists and Native and non-Native scholars provided insights from a range of nations.

The presentation at the Renwick is the third stop on a four venue national tour. The exhibition is accompanied by a beautifully illustrated catalogue, which includes essays, personal reflections, and poems by twenty members of the Exhibition Advisory Board and other leading scholars and artists in the field. It is available for purchase ($39.95) in the Renwick Gallery online store.

Note: Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists was scheduled to be on view from February 21 through May 17, 2020. Its run at the Renwick Gallery was cut short when the Smithsonian closed its museums as a public health precaution to help contain the spread of COVID-19. The museum was closed from March 14 through September 17, 2020.

Visiting Information

Videos

Audio

Credit

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists is organized by the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The exhibition has been made possible in part by a major grant from the Henry Luce Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the human endeavor.

The presentation at the Renwick Gallery is organized in collaboration with the National Museum of the American Indian. Generous support has been provided by the James F. Dicke Family Endowment, Chris G. Harris, the Wolf Kahn and Emily Mason Foundation, Jacqueline B. Mars, the Provost of the Smithsonian, the Share Fund, the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative, and the WEM Foundation.

SAAM Stories

Online Gallery

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.