The year I worked at SAAM’s Lunder Conservation Center changed my life. Things did not always go entirely as I had expected due to COVID-19, but under the circumstances, I was able to compensate with alternative research projects, and completed the major conservation treatment of an oil painting from SAAM’s collection.

Assessing the Damage

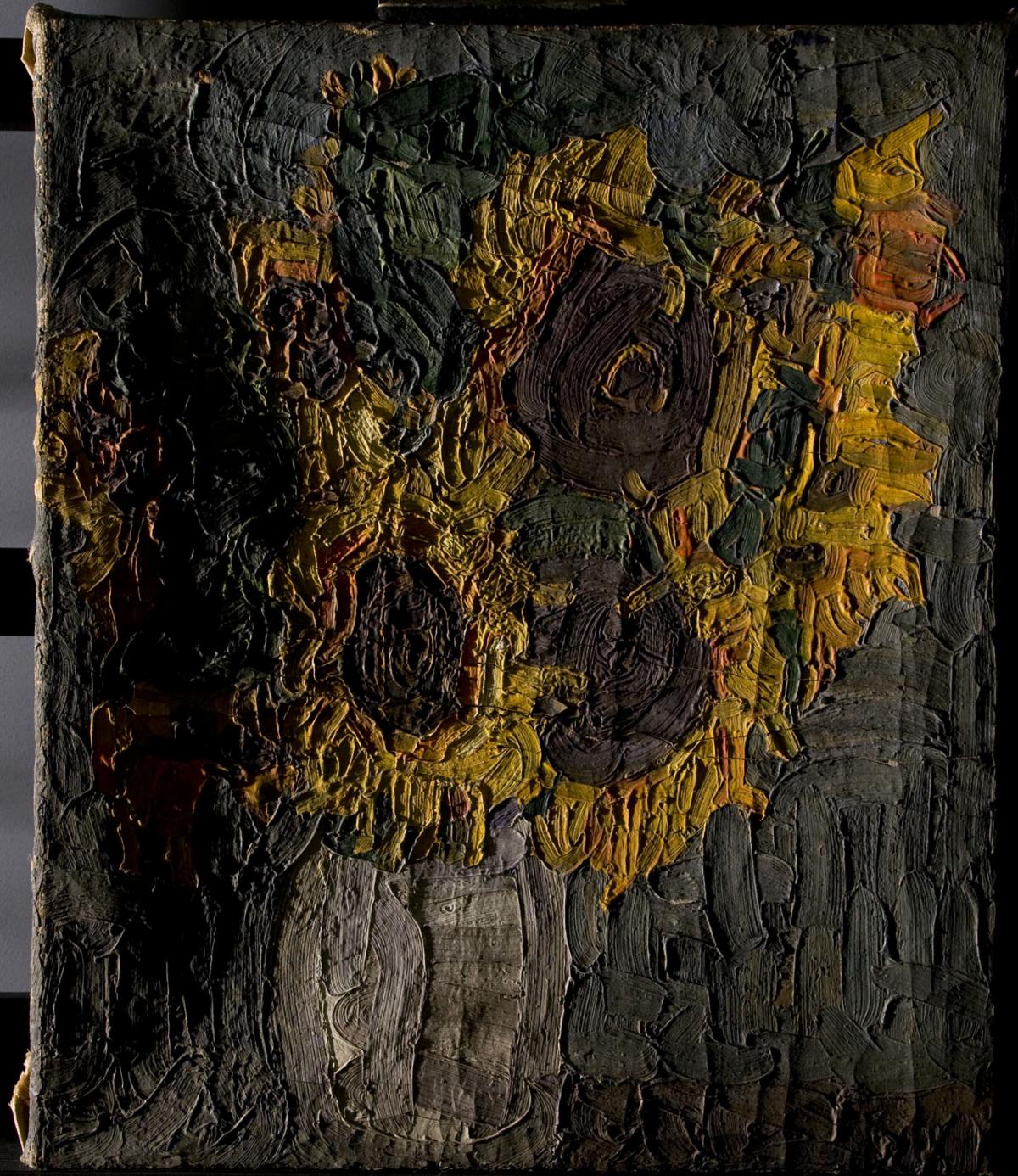

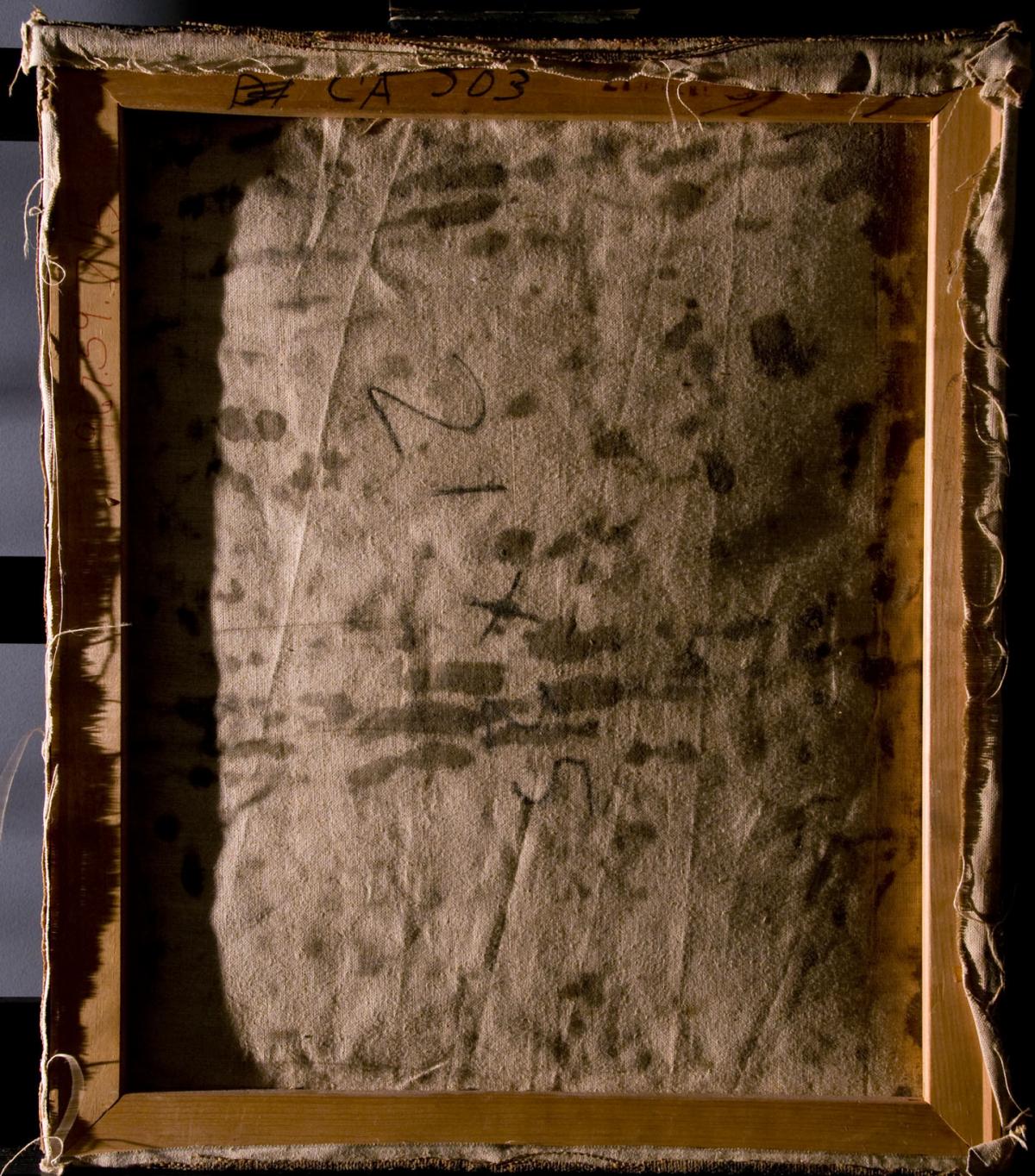

One of the most severe problems was the overall distortion of the painting. As you can see from the figure of the front of the painting above, the paint and canvas layers were deformed and sagged on the stretcher. This contributed to the paint cracks throughout. Judging from the shape of the deformation, the painting seemed to have been stored rolled up before the previous treatment and was loosely attached to the stretcher. The artist used jute fabric, a material often used for gunny bags, and we might assume that he found and reused this material to paint on. Because Johnson did not prime the canvas, it absorbed oil from the paint layer and became brittle; this embrittlement was exacerbated by the fact that jute already contains a lot of lignin, which released acids as it deteriorated, further compromising the canvas. This caused it to lose its flexibility and become static in the deformed state. Eventually, the fibers will tear under stress, even under the weight of heavy paint layers.

Seeking Structure

In an attempt to fix the problem, someone tried to save the work by attaching it to another fabric by impregnating wax-based adhesive into both fabrics. These kinds of treatment are called linings and are intended to mechanically support and reinforce compromised canvases. In this case, however, the lining was detached at several points and almost separated from the painting and provided no support for the original canvas. Another major problem was the extent of damage to the perimeter of the painting: the original tacking margins were partially cut off and part of the painting was bent around the too-small stretcher, resulting in heavy paint losses around the edges. Even areas of the composition were wrapped around to the side. as you can see above in part of the sunflower turning sideways in the middle of the right edge of the painting.

To solve these problems, we had to re-line the painting for a variety of reasons: the painting was detached from the stretcher and the surface of the painting was covered with thin Japanese tissue covered with wheat starch glue. The step, known as a facing, was performed to ensure the safety of the fragile paint layers in the subsequent treatment of reversing the old lining. The lining and the residual lining wax-based adhesive were removed from the painting using heat and organic solvents, and the painting was then gently heated to relax the rigid paint layer and alleviate the distortion. A painting is a composition of multiple substances such as paint, ground, canvas, and lining adhesive/fabric (if the painting was lined). When the surrounding environment changes, each component reacts or degrades differently, which can collapse the composition. A synthetic hot-melt lining adhesive and heavy-weight linen lining fabric were selected, because these materials are relatively resistant to fluctuating environments and are able to keep supporting the artwork as the materials age. After the successful re-lining, the painting was stretched out on an appropriately sized stretcher and no canvas distortions remained. The re-lining was necessary to provide the strength and stability for the painting for its foreseeable future. The treatment enabled me recognize the complex structure of paintings and understanding properties of each component. The lack of one component can upset the overall balance, and on the other hand, one addition can accelerate overall deterioration in exchange for the effectiveness in an aspect.

A Time to Bloom

The painting, which before treatment was too fragile to be displayed vertically without risk to the original paint and canvas layers, has been painstakingly restored. After careful cleaning, correcting the distortions throughout the paint and canvas layers by re-lining, filling and toning losses, the vase of sunflowers stands out in clear colors and bold use of paint. It is as if the sunflowers could once again stretch out in search of sunlight. Recovering the image kept energizing me during the treatment. For several months, or half the duration of my fellowship, the treatment was put on pause since the Smithsonian shut down to prevent spread of COVID-19.

During that period, I helped Gwen Manthey, paintings conservator at SAAM, with the bibliographic surveys about solid supports like fiberboard, which have been used as paintings’ supports or their lining substrates. I also spent the rest of the time collecting and sorting out the information on methods of reversing the linings as I searched online or touched base with several conservators and researchers in the same field, which would develop into my PhD dissertation in Tokyo University of the Arts, Japan. After I gained access to the museum in mid-August, I could touch the painting two or three times a week and focus on and achieve the completion of the treatment thanks to my supervisors’ arrangement.

I am grateful to everyone at Lunder who gave me opportunities. I strongly hope that as the pandemic comes to an end, many visitors will be able to enjoy these lively sunflowers.

Saki Kunikata was a 2019-2020 Lunder Conservation Fellow