Shanti Boyle is an intern with SAAM's Office of External Affairs and Digital Strategies.

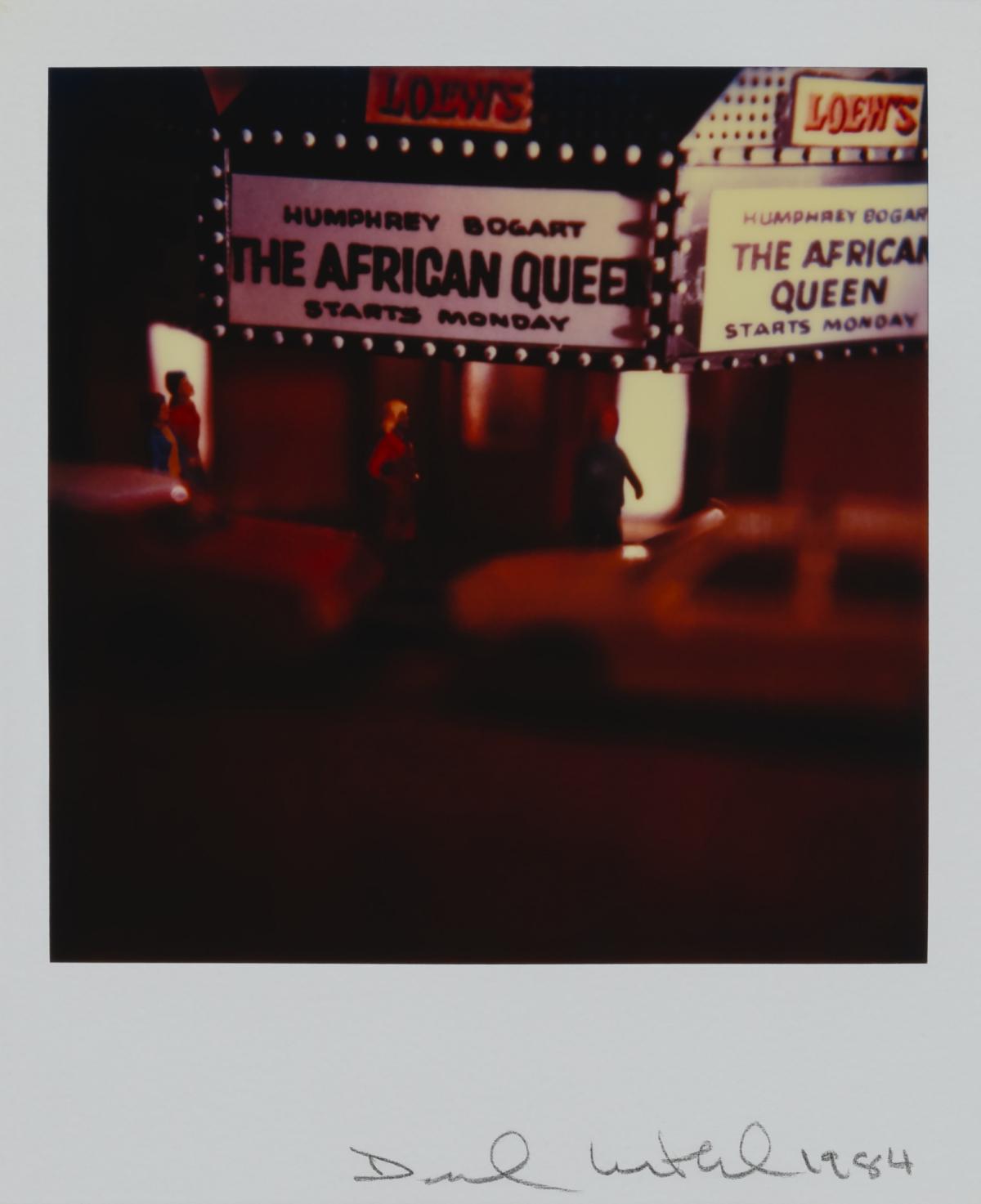

Two out of the six series of images in the current exhibition, American Myth & Memory: David Levinthal Photographs, focus on the representation of women in the media, with a third, "Modern Romance," vying for a spot. "American Beauties" and "Barbie" blatantly highlight antiquated conceptions of attractiveness, ones perpetuated and memorialized by media. On the other hand, "Modern Romance" offers a blanket statement on film noir itself by containing more general subjects, such as a stadium or a street corner.

One subject in particular begs attention: the bedroom. This already-gendered space becomes a soapbox for talking about the portrayal of women in film noir and, more broadly, media, when viewed through the lenses of Levinthal’s camera. Three of Levinthal’s photographs in particular provide the perfect platform.

If you have seen the exhibition (and if you have not, it closes on October 14), you know which set of photographs I am referring to. Displayed apart from the smaller, dark snapshots, these high-exposure images certainly expose much while simultaneously obscuring the scenes. The photographs depict a woman in a bedroom. It is unclear whether or not the images show the same bedroom. Regardless, the women privately model in various postures. In one image, a woman undresses herself. In another, she lies nude on a bed propped up on an elbow, a Venus of Urbino with a Mid-Atlantic accent. The last scene contains a woman standing in a doorway in front of another figure who mirrors her. The other figure is amorphous, though in keeping with film noir tropes, we can imagine it to be either her lover or her enemy, but almost certainly a man. These photos, aided by high exposure and less-than-perfect perspectives, give a sense of spying through Norman Bates’ peephole in Psycho. The three Marion Cranes do not give any indication that they know they are being watched.

All six of the series featured in the exhibition are accompanied by commentary from a celebrity or expert in the field represented. Ann Hornaday, chief film critic of the Washington Post, shared her thoughts about film noir. Levinthal’s emphasis on voyeurism exemplifies Hornaday’s observation of national alienation following World War II. The film noir women became surrogates of anxiety, manifestations of a grudging reality that reflected how Americans felt about their own global visibility. The unsuspecting women in Levinthal’s photographs highlight the idea that someone is always watching. Their vulnerability in these scenes, fabricated by both society and the artist, represent the national emotion at the time. Yet Levinthal turns this representation on its head by making us—the museum-goers—voyeurs culpable for the alienation of the subjects.

Levinthal’s "Modern Romance" removes the fantasy from film noir and illuminates the darkness from which the genre was born. Levinthal asks us to be skeptics of our history and to consider that what is American myth now does not determine what future America will remember as truth.

American Myth & Memory: David Levinthal Photographs remains on view through October 14, 2019.