In honor of Pride month, we've launched an occasional series where SAAM staff take a close look at meaningful works of art in our collection.

Nancy Grossman is best known for her sculptures of human heads—carved wood which is then painted white, tightly covered in sewn black leather, and detailed with straps, string, zippers, buckles, or bolts. The noses are always exposed, while the mouths are consistently concealed.

The artist began this body of work—which also includes drawings, like 5 Strap I—in the late 1960s, when she was deeply depressed and isolated. To Grossman, the masks symbolize “self-imposed [or] societally-imposed” restrictions, as well as the “second skin” one develops as protection from the outside world. She frequently refers to the heads as self-portraits, relating them to the “bondage” she experienced in her childhood.

When I first encountered one of the heads in person, I couldn’t help but see myself in it too. I was a 24-year-old closeted gay man and I felt just as stuck as the life-size sculpture staring back at me. Early in my childhood, I built up a barrier to shield myself from a homophobic society. I learned to hide the parts of myself I had learned to hate, and buried the thoughts and desires I didn't want to confront. But what were once tools for self-preservation were now stifling me and stunting my growth.

“It takes a long time to undo what many people have done to you,” Nancy Grossman said wisely in a 1974 interview. But I knew I had to start. I had to start shedding these restrictions—unlearning and undoing—in order to flourish and move forward.

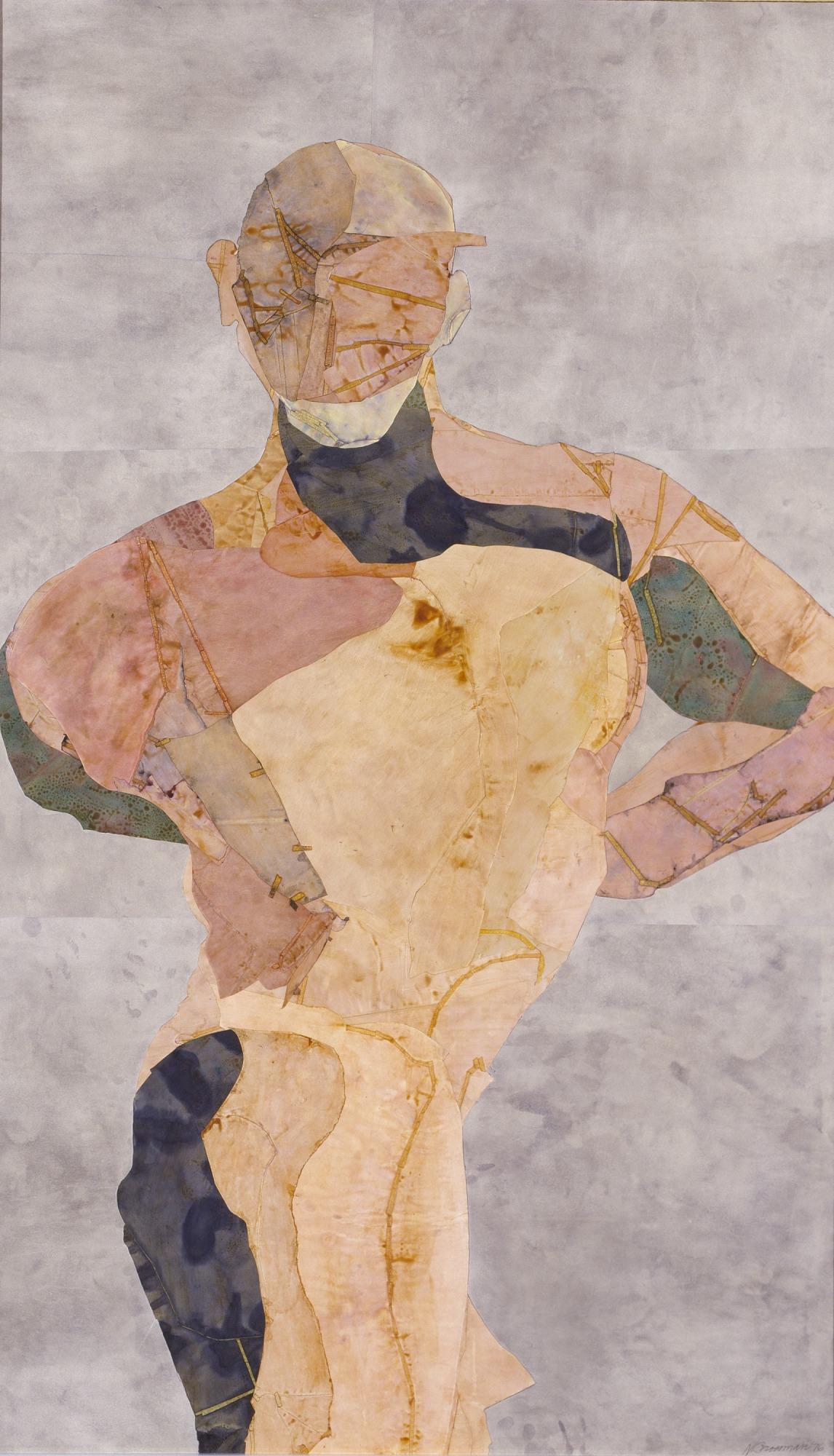

That's what I see in another of her works, the beautiful 1976 collage Twisting Column Figure—a person in the process of undoing. In fact, when I look at this piece, I see the flurry of emotions—the joy, empowerment, autonomy, and vulnerability—I felt once I started my coming-out journey. It was scary, yes. But I also felt a newfound lightness. I was done living inside my head and was finally in touch with my body, my full being, my true self.

This piece is obviously a departure from the monochromatic and static heads, but even in comparison to Grossman's other “collage paintings” from the same period, it is an outlier. Most of the other figures are confined or limited in one way or another. They have titles like Bound Figure and Tethered Figure with Rising Arms. Their arms are in slings or tied behind their backs. Even in the paintings where physical restraints aren’t present—like T. C. As A Young Man—the figures are seated and quiet, tightly coiled and folding into themselves.

Twisting Column Figure, on the other hand, is energetic and flamboyant, moving freely and spreading confidently across the composition. With hands firmly planted on hips, the body quickly turns out and thrusts forward to face the viewer, possibly stretching after a period of bondage or dormancy. The subject is boldly commanding the space but is also supremely vulnerable. Aside from the thinly veiled face, the figure’s fragile skin—patches of colorful dyed paper delicately joined by masking tape—is raw to the elements. There is no armor or flattening façade to guard it.

It takes great courage to begin the daunting task of unbinding, untethering, and slowly becoming one’s authentic self, unburdened by societal conditioning and personal insecurities. Twisting Column Figure represents the strength, freedom, resilience, and possibilities that come once we commit to the process.

Nathaniel Phillips is a graphic designer at SAAM.