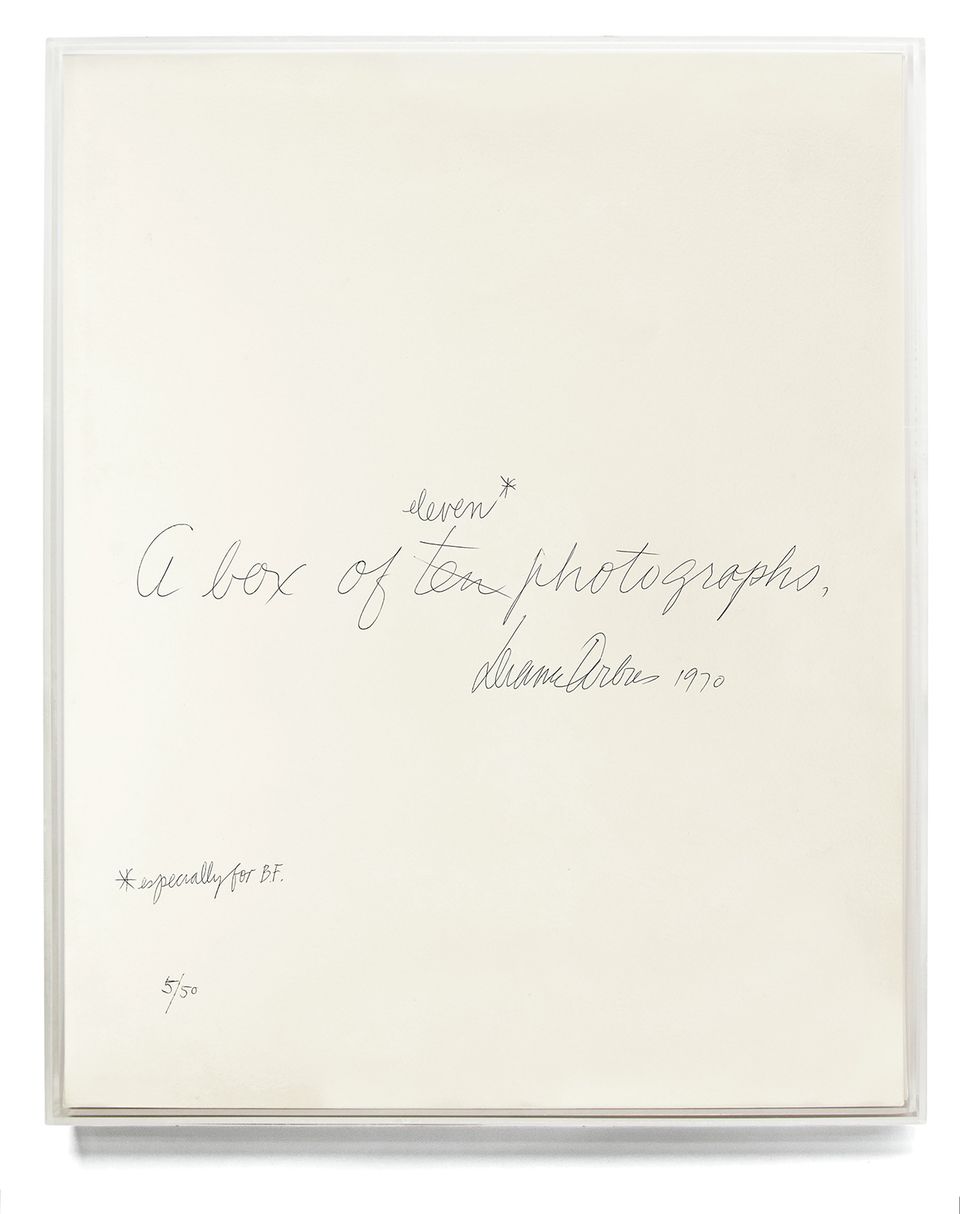

Diane Arbus: A box of ten photographs

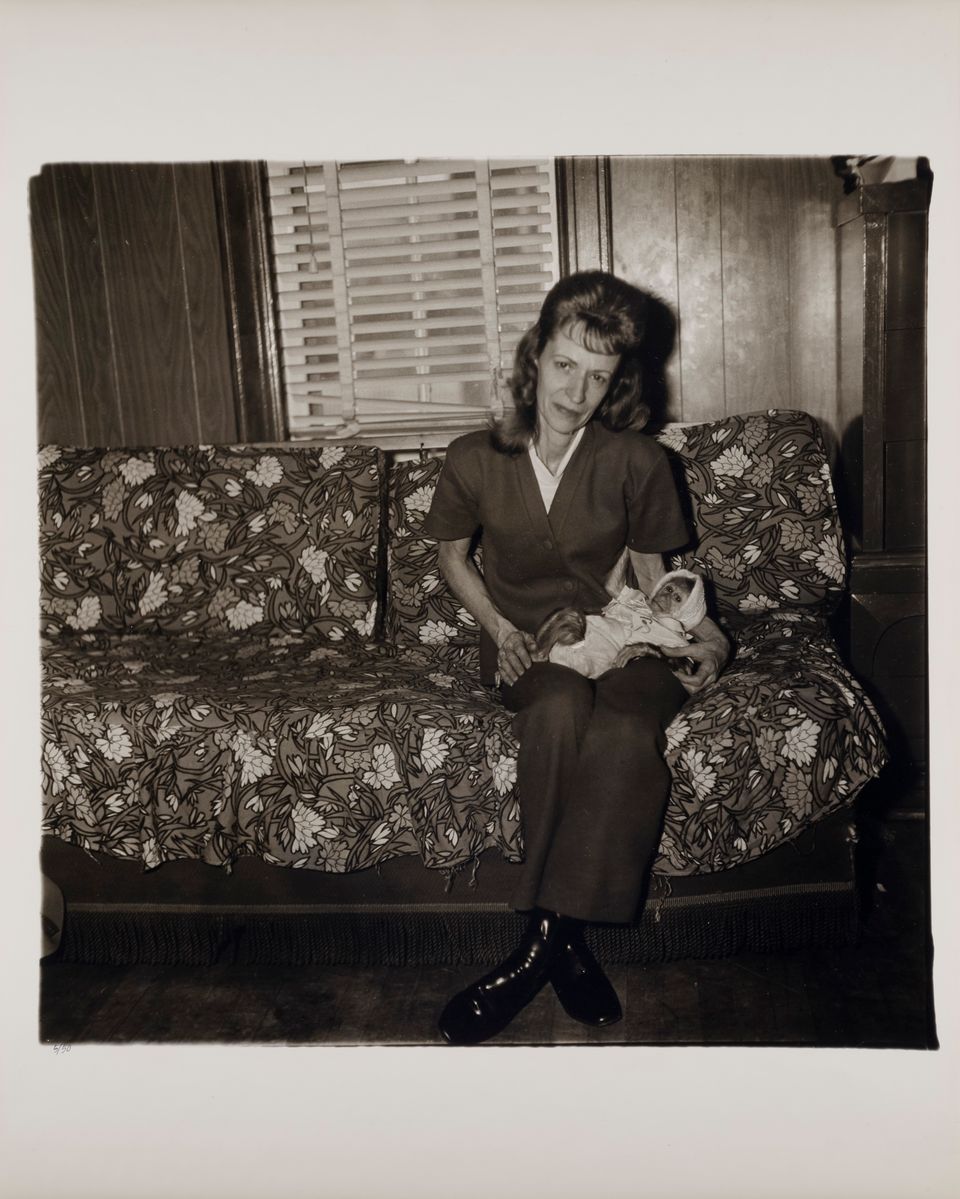

Diane Arbus, Mrs. Gladys 'Mitzi' Ulrich with the baby, Sam, a stump-tailed macaque monkey, North Bergen N.J. 1971, gelatin silver print, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase. © 1971 The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC

“They are the proof that something was there and no longer is. Like a stain. And the stillness of them is boggling. You can turn away but when you come back they’ll still be there looking at you.”

—Diane Arbus, 1971

In late 1969, Diane Arbus began to work on a portfolio. At the time of her death in 1971, she had completed the printing for eight known sets of A box of ten photographs, of a planned edition of fifty, only four of which she sold during her lifetime. Two were purchased by photographer Richard Avedon; another by artist Jasper Johns. A fourth was purchased by Bea Feitler, art director at Harper’s Bazaar, for whom Arbus added an eleventh photograph.

Description

This exhibition traces the history of A box of ten photographs between 1969 and 1973, using the set that Arbus assembled for Feitler, which was acquired by SAAM in 1986. The story is a crucial one because it was the portfolio that established the foundation for Arbus’s posthumous career, ushering in photography’s acceptance to the realm of “serious” art. After his encounter with Arbus and the portfolio, Philip Leider, then editor in chief of Artforum and a photography skeptic, admitted, “With Diane Arbus, one could find oneself interested in photography or not, but one could no longer. . . deny its status as art. . . . What changed everything was the portfolio itself.”

In May 1971, Arbus was the first photographer to be featured in Artforum, which also showcased her work on its cover. In June 1972, the portfolio was sent to Venice, where Arbus was the first photographer included in a Biennale, at that time the premiere international showcase for contemporary artists. SAAM organized the American contribution to the Biennale that year, thereby playing an important early role in Arbus’s legacy.

John Jacob, the McEvoy Family Curator for Photography at SAAM, organized the exhibition. The catalogue, copublished with the Aperture Foundation, features an in-depth essay by Jacob that presents new and compelling scholarship and adds significant detail to the period between her death and the 1972 posthumous retrospective at MoMA.

Visiting Information

Publications

Videos

Credit

Diane Arbus: A box of ten photographs is organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Generous support has been provided by the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Nion McEvoy and Leslie Berriman, RayKo Photo, the Bernie Stadiem Endowment Fund, the Trellis Fund, and Robin Wright and Ian Reeves.

SAAM Stories