Artwork Details

- Title

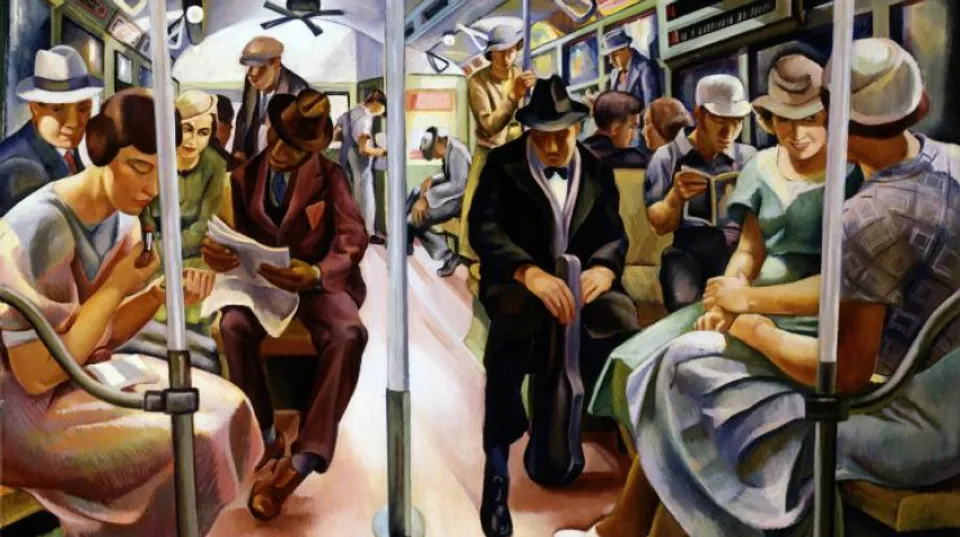

- Subway

- Artist

- Date

- 1934

- Location

- Dimensions

- 39 x 48 1⁄4 in. (99.1 x 122.6 cm.)

- Credit Line

- Transfer from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service

- Mediums

- Mediums Description

- oil on canvas

- Classifications

- Subjects

- Figure group

- Figure group

- Recreation — leisure — reading

- State of being — other — sleep

- Recreation — leisure — conversation

- New Deal — Public Works of Art Project — New York City

- Recreation — leisure — grooming

- Architecture — vehicle — subway

- Object Number

- 1965.18.43

- Research Notes

Artwork Description

Furedi takes a friendly interest in her fellow subway riders, portraying them sympathetically. She focuses particularly on a musician who has fallen asleep in his formal working clothes, holding his violin case. The artist would have identified with such a New York musician because her father, Samuel Furedi, was a professional cellist.

1934: A New Deal for Artists exhibition label

The New Deal ushered in a heady time for artists in America in the 1930s. Through President Franklin Roosevelt's programs, the federal government paid artists to paint and sculpt, urging them to look to the nation's land and people for their subjects. For the next decade — until World War II brought support to a halt — the country's artists captured the beauty of the countryside, the industry of America's working people, and the sense of community shared in towns large and small in spite of the Great Depression. Many of these paintings were created in 1934 for a pilot program designed to put artists to works; others were done under the auspices of the WPA that followed. The thousands of paintings, sculptures, and murals placed in schools, post offices, and other public buildings stand as a testimony to the resilience of Americans during one of the most difficult periods of our history.

Smithsonian American Art Museum: Commemorative Guide. Nashville, TN: Beckon Books, 2015.

Videos

Related Books

Related Posts