Palmer Hayden

- Also known as

- Peyton Cole Hedgeman

- Palmer Cole Hayden

- Palmer C. Hayden

- Born

- Widewater, Virginia, United States

- Active in

- Boothbay, Maine, United States

- Paris, France

- Biography

By 1940 Palmer Hayden was known for his narrative scenes of New York's urban life and the rural South. Like a photographer taking snapshots, he depicted black subjects during unguarded moments in their daily routine. His characterizations-sometimes humorous, sometimes unflattering-are nonetheless caring and proud. Described by Hayden's compelling use of line, they possess the immediacy of popular illustrations.

Although the artist's studio is a time-honored theme, Hayden's intention in The Janitor Who Paints[SAAM, 1967.57.28] is more provocative than usual because he described it as a "protest painting" in a 1969 interview. An easel, palette, and brushes share space with a bed, nightstand, feather duster, and broom. Is Hayden's subject an amateur, painting portraits of his family and friends in his spare time at home? Or is he a professional artist, forced to support himself in a modest occupation and to combine his creative and domestic spheres in one setting? Having taken odd jobs including housecleaning to support himself, Hayden experienced the economic hardships of many black artists, and the painting has often been interpreted as both a self-portrait and a statement on adversity.

The most immediate source for the element of protest that Hayden associated with the work, however, was his friendship with Cloyd Boykin, an older African-American painter who supported himself as a janitor:"I painted it because no one called Boykin the artist. They called him the janitor." Hayden incorporated details such as the beret and the subject of mother and child to reinforce the sense of artistic identity, while the clock alludes to the workman's schedule.

Initially self-taught, Hayden sought training in New York and Paris, yet his style has frequently been described as primitive. In The Janitor Who Paints, the figures' oversized hands and intense, cartoonlike expressions, as well as the freely treated space in which shapes are outlined as relatively flat areas of color, recall the simplified forms of American folk art. Actually, these elements owe as much to the broader influences of African and modern art that Hayden encountered in Paris as to his highly personal approach to interpreting the vitality and challenges of African-American life.

Lynda Roscoe Hartigan African-American Art: 19th and 20th-Century Selections (brochure. Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art)

- Artist Biography

"I decided to paint to support my love of art, rather than have art support me." — Palmer Hayden quoted in Nora Holt, "Painter Palmer Hayden Symbolizes John Henry," New York Times, 1 Feb. 1947.

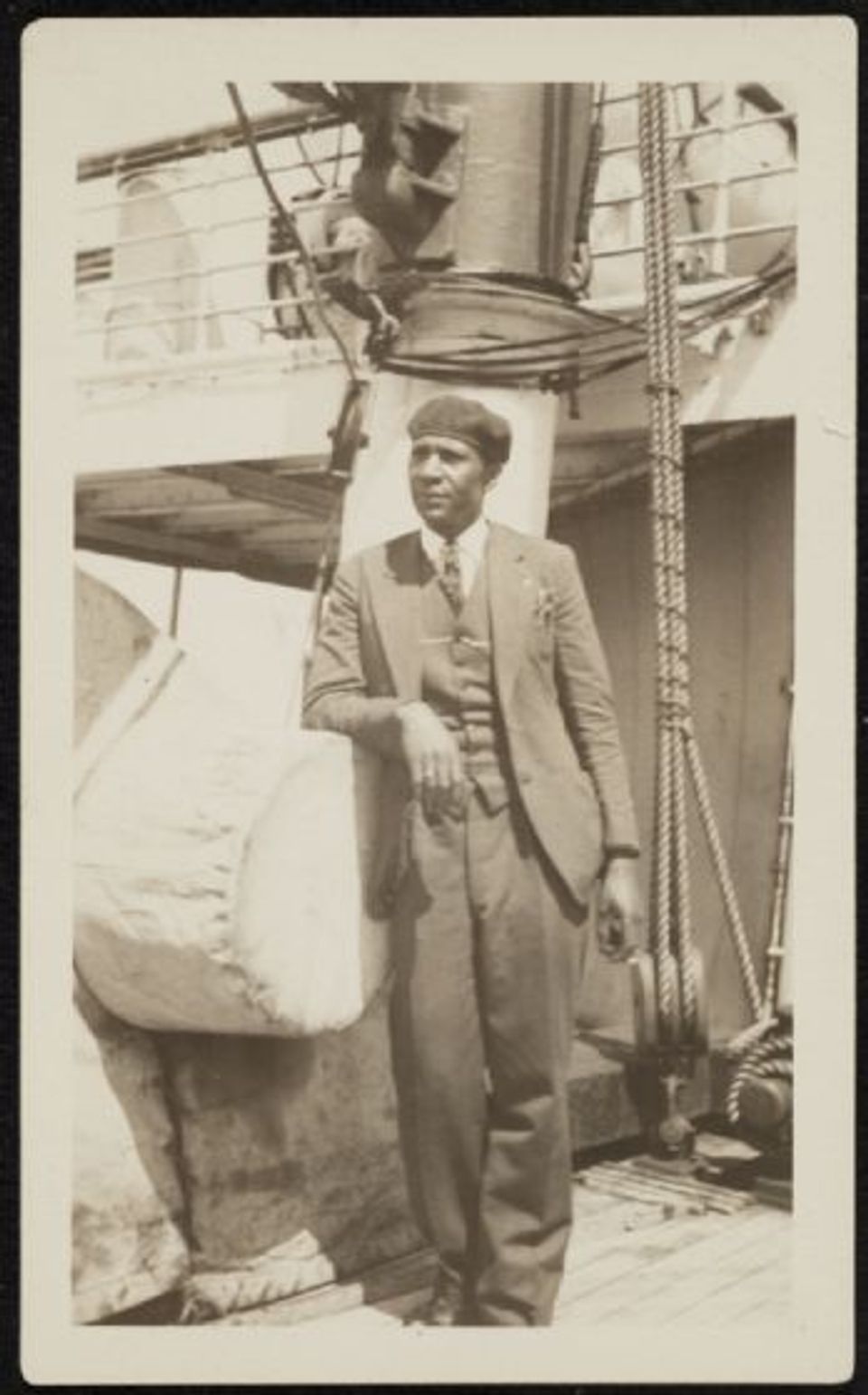

Palmer Hayden was an artist whose association with the Harlem Renaissance was more spiritual than stylistic. Born on January 15, 1890, in Widewater, Virginia, to Nancy and John Hedgeman, Hayden was christened Peyton Cole Hedgeman but later changed his name to Palmer Hayden, the name he signed on all of his works. Hayden's interest in drawing began during his childhood. His first formal contact with art did not occur, however, until his enlistment in the army during World War I, when he enrolled in a drawing correspondence course. Hayden's military duty took him to West Point and the Philippines. Following his discharge from the army, Hayden moved to New York and worked part-time while studying art with Victor Perard at the Cooper Union School of Art.

During his early years Hayden also studied painting with Asa G. Randall at the Boothbay Art Colony in Maine in 1925. Hayden was awarded a working fellowship to Boothbay, and devoted most of his time to painting boats and marine subjects. His Boothbay period paintings were exhibited in New York in 1926 at the Civic Club and won two Harmon Foundation awards—the coveted gold medal and a cash prize of $400. With this money and a personal contribution from a patron, Hayden sailed for Paris in 1927, and studied in Brittany and in Paris at the École des Beaux Arts. Within a year Hayden had distinguished himself and mounted a one-man show at the Galerie Bernheim in Paris in November 1928. He also exhibited in group shows in Paris at the Salon des Tuileries in 1930 and the American Legion Exhibition in 1931. Hayden's portrayal of African-American subject matter in many of his paintings in the latter show was unusual in Paris at that time.

Hayden was in Paris during the final years of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, but he had lived in New York during the formative years of that pivotal period. He knew Harlem Renaissance artists and shared their efforts, triumphs, and frustrations. Hayden maintained close contact with the Harmon Foundation while in the United States, and exhibited annually in the Harmon Foundation shows from 1928 to 1932 when he was in Paris.

Although Hayden received thorough academic training in New York, Maine, and Paris, his works always retained a flat naive character, which he developed independently during his youth. One of Hayden's best-known early works is Fétiche et Fleurs of 1926, which clearly linked Hayden with the African-Cubist tradition of Harlem and Paris. The small still-life composition depicts a vase of lilies, an ashtray, and a Gabonese Fang head on a table covered with a Kuba textile from Zaire. This painting was one of the earliest by an African-American artist to incorporate actual African imagery, and was awarded Mrs. John D. Rockefeller's prize for painting in the Harmon Show of 1933.

Following his return from Paris in 1932, Hayden worked on the United States Treasury Art Project and the W.P.A. Art Project from 1934 to 1940, and painted scenes of the New York waterfront and other local subjects. During the late 1930s Hayden developed a consciously naive style, which represented various aspects of African-American life. One of the first paintings that heralded Hayden's new style was Midsummer Night in Harlem, 1938, in which he effectively evoked the mood of Harlem's residents congregating outside to escape the heat inside the tenements. Despite the flat forms and stylized figures, the compositional arrangement and treatment of perspective reveal Hayden's academic training. African-American art historian James Porter apparently misunderstood Hayden's objectives when he criticized Midsummer Night in Harlem as a talent gone astray," and compared the painting to "one of those billboards that once were plastered on public buildings to advertise black face minstrels." Hayden insisted, however, that he was not striving for satirical effects in his African-American folk paintings, but that he wanted to achieve a new type of expression.

In 1944 Hayden began painting the Ballad of John Henry series that would occupy him for the next ten years. The series comprises a group of twelve paintings depicting scenes from the life of the legendary African-American folk hero who inspired the ballad named after him. An exhibition of these paintings and others dealing with African-American folklore was held at the Countee Cullen Library in Harlem in 1952. Hayden was also represented in the large exhibition, The Evolution of the Afro-American Artist, sponsored by the City University of New York, the Urban League, and the Harlem Cultural Council and presented in the fall of 1967 in the great hall of the City University. From the late 1960s until his death in 1973, Hayden continued to paint subjects based on African-American themes, but in a more cosmopolitan manner than his earlier works.

Regenia A. Perry Free within Ourselves: African-American Artists in the Collection of the National Museum of American Art (Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art in Association with Pomegranate Art Books, 1992)

Luce Artist BiographyPalmer Hayden, born Peyton Cole Hedgeman, began sketching at an early age. He moved to New York in his early twenties to pursue art and studied at several prominent schools, while working odd jobs to support himself. After six years of part-time art studies, Hayden won the first Gold Medal in Fine Arts for a marine watercolor from the Harmon Foundation, a nonprofit that supported African Americans in the arts. He went on to study in Paris, where he met African American émigrés Hale Woodruff and Henry Ossawa Tanner. While there, Hayden started to focus on images of African American life, rather than the marine scenes that first established his reputation as an artist. He returned to New York in the early 1930s and later worked for the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Although he exhibited his art regularly, art contemporaries criticized Hayden for creating what they perceived to be caricatures of African Americans. Today Hayden's body of work is recognized for its focus on the turmoil, and triumph, of the African American experience.