Born 1953 in Muncie, IN

Lives and works in San Francisco, CA

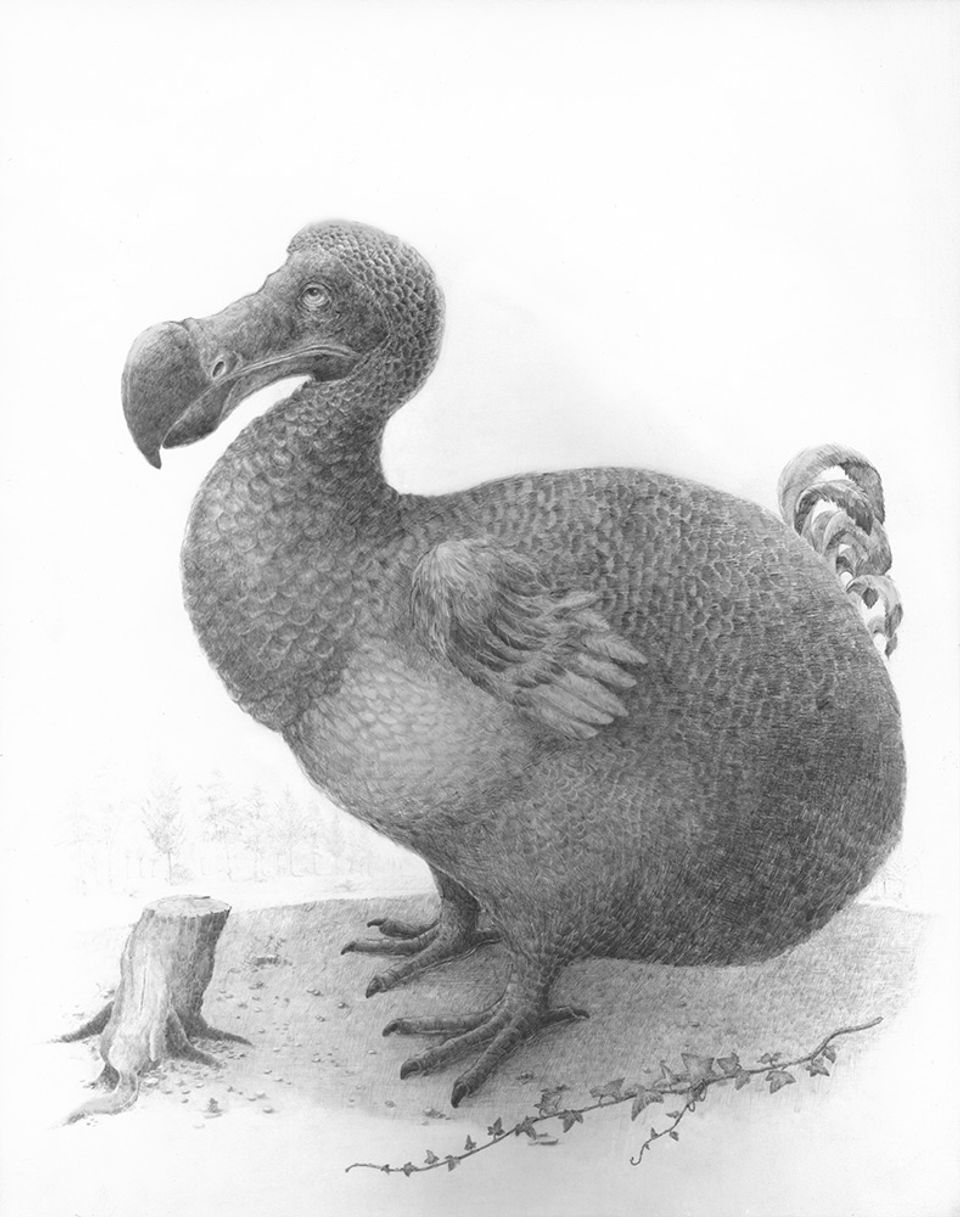

David Beck’s meticulously crafted paintings, drawings, and sculptures evoke both curiosity and wonder. Each intimately scaled object references a range of sources, from medieval miniatures to American folk art and eighteenth-century mechanical toys. Beck has been depicting the dodo for nearly forty years, beginning with sketches based on an exhibit at the Museum of Natural History in New York. Beck’s diminutive sculptures evoke the surprise and discovery of childhood, but these playful curiosities belie a serious message about vulnerability, loss, and longing.