Jeff Gates: Can you give us a brief overview of your research?

J.V. Decemvirale: My research looks at Black and Latinx art spaces and activism in Los Angeles from 1968 to 1984. I focus on the interventions artists made in institutional art spaces and the early histories of two alternative art spaces: Self Help Graphics and Art and the Museum of African American Art. During my time at SAAM, I worked at theorizing a place for Self Help Graphics and Art within an emerging history of what is called social practice or socially-engaged art, and presented a final talk on my findings. In regards to the Museum of African American Art, I worked through numerous artist papers and institutional records pertaining to the history of Black arts activism in Los Angeles.

My project really began in 2011, when I visited more than fifty of the exhibitions that made up the first iteration of the J. Paul Getty’s Pacific Standard Time. I had just gotten to the Getty as a graduate intern and returned to my native city after being a way for a while, and the spectacular overview of LA’s cultural landscape gave me a lot to think about. What quickly became evident was that there were very few exhibitions about Black and Latinx artists. I dove into the exhibition catalogues and started to independently research who set up Black and Latinx artist networks in the late 1960s and 1970s, who was doing the activism, what were their motivations, and who was establishing these community art centers. I began conversing with artists from that generation and saw that many had decided the studio and solitary art practice they were taught in art school wasn’t enough. The more I researched, the more I realized how segregated and distant their stories were from the mainstreams of art history I had been taught.

JG: What have you found in the archives?

JVD: The Charles White Papers in the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art are a treasure trove, particularly for my research. White not only kept everything, but because he was so well-known and loved for both his politics and artworks, arts activists all over the country sent him their flyers, letters, etc. If you mounted a Black art show or created a Black arts association, you sent your materials to White.

White’s papers are probably the best archive on the history of Black arts activism in Southern California, as LA’s own archival holdings for this period are woefully incomplete. White’s papers contain a wealth of material on the Black Arts Council, one of Los Angeles’ most important black arts advocacy groups, founded and chaired by two Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) preparators, Cecil Fergerson and Claude Booker. The council began to demand Black exhibitions, programming, and staff from LACMA. While negotiations with museum leadership dragged on, the council could not wait and established itself as a peripatetic curatorial agency, curating exhibitions and giving lectures on Black art history in churches, libraries, and schools in mostly Black neighborhoods.

JG: What about the Mexican American community in Los Angeles?

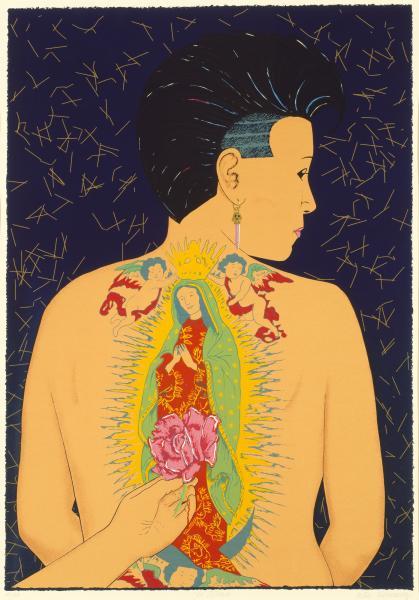

JVD: I was really intrigued by Self Help Graphics & Art, the oldest Chicanx art center still in existence in East Los Angeles. Self Help was unique because of their artistic philosophy based in facilitating participatory and performative art projects for their Chicanx neighbors. The center was established in 1972 by a Franciscan nun and artist, Sister Karen Boccalero and two gay, Mexican artists, Carlos Bueno and Antonio Ibañez. Originally envisioned as more of an atelier art center, where anyone could come in and make work in a studio situation, they, along with other artist collectives and art spaces like Goez Art Studio and Asco, brought performance and artistic frameworks out into the street.

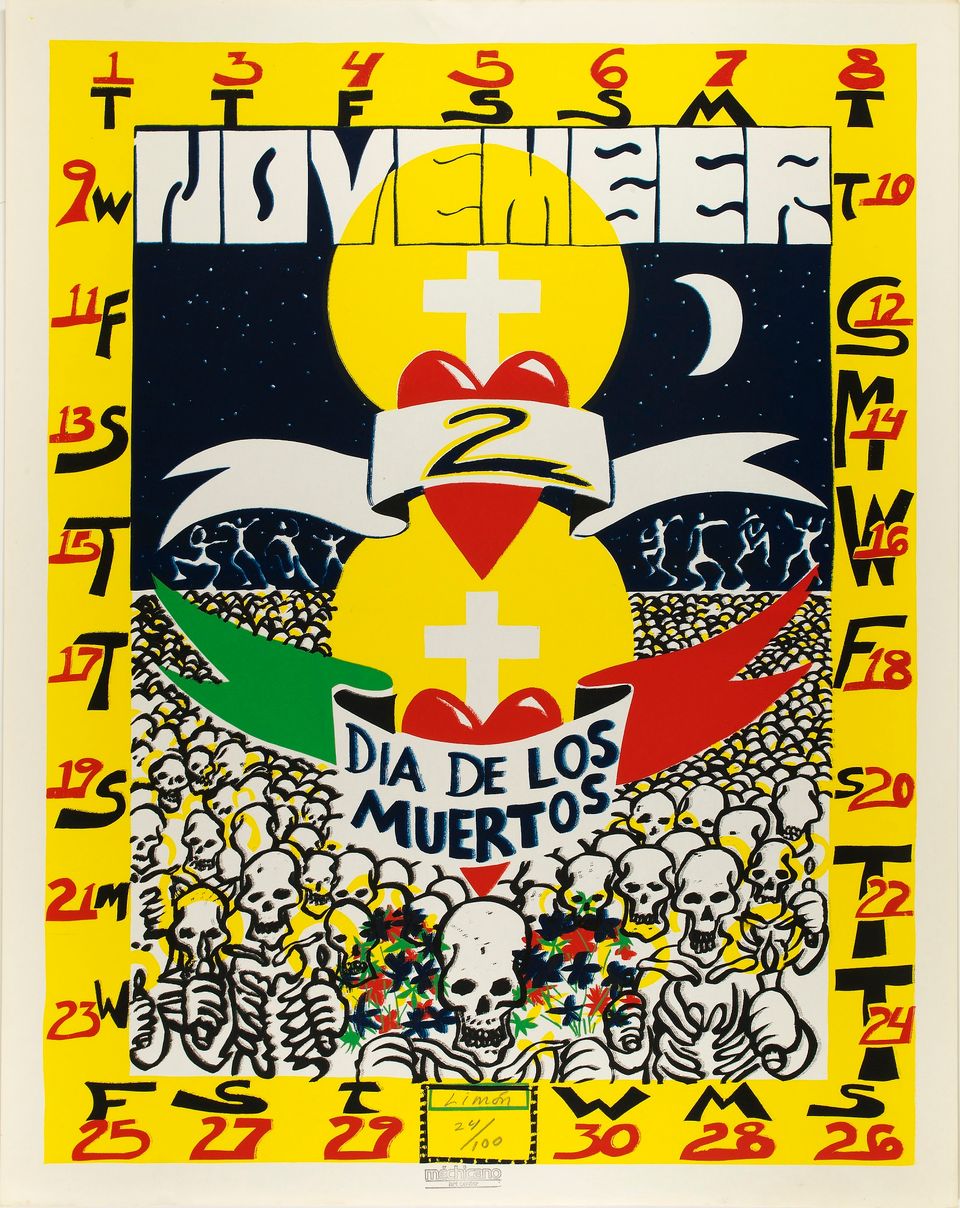

In 1973, Self Help revived and improvised on an ancient indigenous Catholic Mexican ritual celebrating the dead, known as Día de los Muertos. The original Mexican celebration was a somber affair taking place in cemeteries at night. Self Help’s version consisted of a parade in which local artists and neighbors dressed up and carried homemade artworks. The parade would conclude at a cemetery honoring those killed by gang violence.

Where Día de los Muertos called forth and manifested the Chicanx community in the streets, Self-Help’s Barrio Mobile Art Studio brought art spaces to their Chicanx constituency wherever they were. Antonio, Carlos, and Sister Karen converted the inside of a retired UPS delivery van into a darkroom and, with four artists at a time, the mobile art space traveled to schools, community colleges, juvenile halls and probation camps, senior centers, and housing projects offering Chicanx and Mexican art history lessons, as well as a wide range of projects around Mexican-related themes.

Practices like these show the lengths artists went to, in both the Black and Latinx communities, in order to test art’s capacity to be meaningful and pertinent in everyday conditions. Not a model for every artist or every arts institution, their histories deserve to be recognized precisely because they reveal to us the dominant values of our current art world, as well as posit what an alternative art world might look like.

JVD: Jeff, you were one of the original artists with the Barrio Mobile Art Studio. What do you remember about your time there?

JG: I began working with Antonio, Carlos, and Sister Karen right after getting my master's degree in fine arts from UCLA in 1975. I was one of the photography teachers who traversed East LA in that van. It was the first community-based art project I was involved in and, in many ways, set the stage for my future work as an artist. I was the only Anglo in the group. I’m not sure that would happen these days. But, I grew up in a Latinx part of the San Fernando Valley. My high school was multicultural before the word was coined. My mother grew up in East LA just before World War II. Back then, Latinos, Jews, Blacks, and Asians were integral parts of the community. Living now in Washington, DC, my wife and I were lucky to find such a neighborhood in which to raise our children. In many respects, I think our society is more segregated now, both physically and in spirit. Back then, I felt both comfortable and welcomed at Self Help and in the communities we worked in.

JVD: The BMAS was an important and experimental laboratory for other artists as well, like Carlos Almaraz, Linda Vallejo and Michael Amescua. A younger Chicanx artist, Dewey Tafoya, has reinstituted the project and has been making some politically-engaged screen prints.

JG: So, what’s next for you?

JVD: Well, now that I have concluded the research phase of my dissertation, I will be moving to mid-state New York for a self-imposed writing retreat to complete it. Earlier this month, I gave a paper entitled “Lessons in Disobedience: Samella Lewis and the Public American Art Museum” at “My Art Speaks for Both My Peoples,” a symposium about Elizabeth Catlett at the University of Delaware. That paper looked at the attempts by Catlett and Lewis at desegregating the public American art museums. On October 28, I will be at Notre Dame University to share some of my research on Self Help Graphics co-founder Carlos Bueno at the “Self Help Graphics at Fifty—Art History Colloquium” that is bringing together authors of an upcoming anthology celebrating the organization’s fiftieth anniversary.

J.V. Decemvirale is a doctoral student at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He was a SAAM predoctoral fellow in Latinx art from 2018 to 2019, and his fellowship was supported by the Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center. Jeff Gates is an artist and one of the founders of Eye Level, the first blog at the Smithsonian. He was its managing editor for thirteen years before his retirement. In the 1970s, he was an artist and teacher with the Barrio Mobile Art Studio in East Los Angeles.

Celebrate Día de los Muertos family day at SAAM this Saturday from 11:30am–3pm in the Kogod Courtyard.