Bones from the last ice age might be standard for a natural history conservator, but it’s not the norm here at an art museum. As an objects conservator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, I preserve, repair, and study all types of objects made of ceramic, glass, stone, plastic, metal, wood…and now, subfossilized mastodon bone.

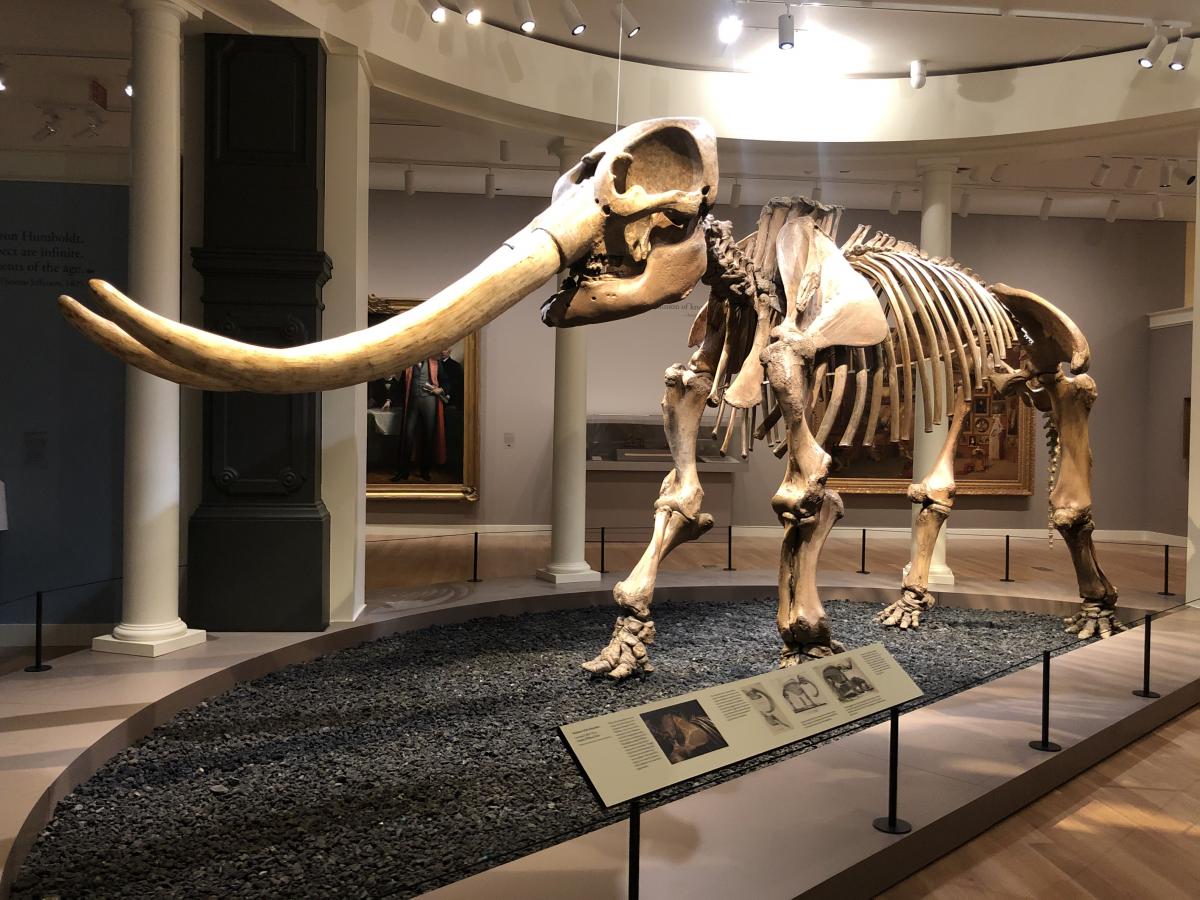

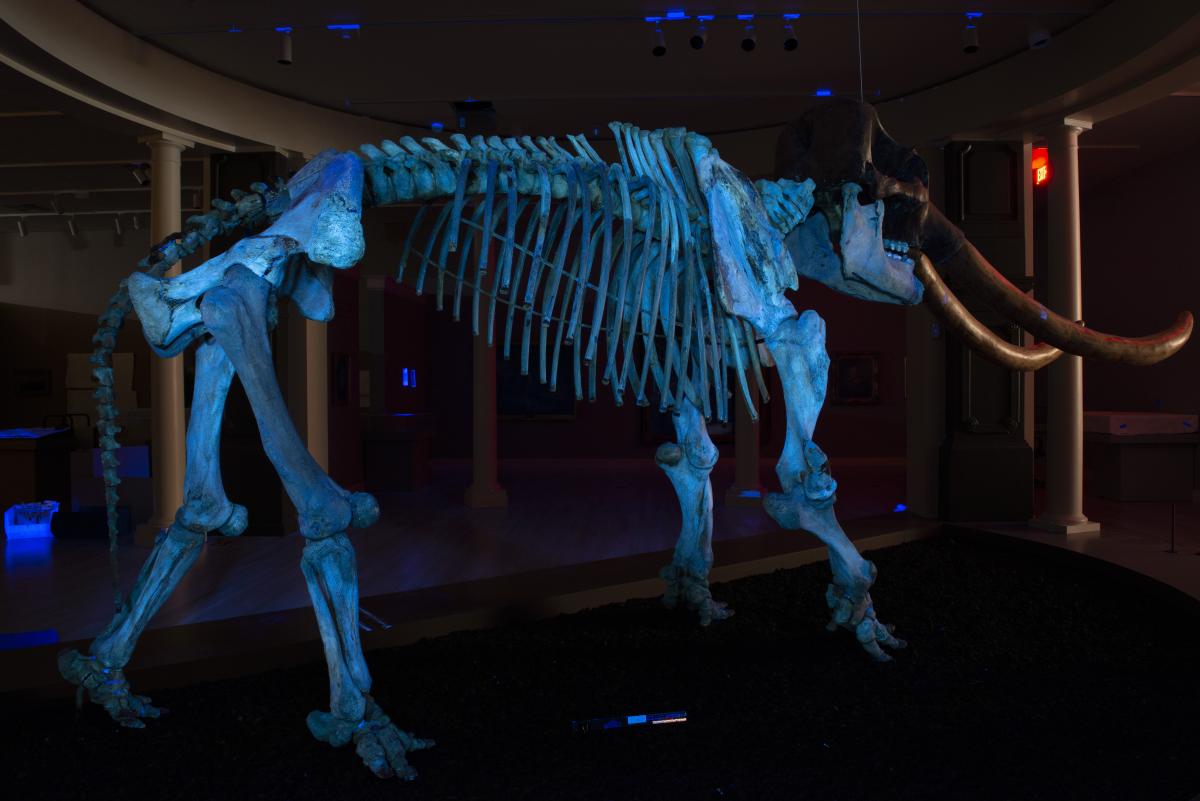

As part of the international team that brought what is affectionately known as the "Peale Mastodon"—the first nearly complete mastodon skeleton collected in the world—safely from Germany to our museum for the Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture exhibition, I was fascinated with the artistry surrounding this massive beast. I found myself asking the same questions I pose when approaching a sculpture, and the further I dove in, the more mysteries I discovered.

Where was it found and how was it displayed?

This mastodon fossil was the largest known terrestrial being when its bones were discovered on a farm in Newburgh, New York, in 1798. News of the discovery reached Philadelphia and the American painter and naturalist Charles Willson Peale—a friend and contemporary of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington—quickly secured the opportunity to excavate the rest of the bones in August 1801. Accounts tell us some parts disintegrated when they pulled them from the watery pit: the tusks fell apart and the lower jaw and several ribs were never found. But the skeleton was nearly complete.

The Peale family immediately began reconstructing the bones in Philadelphia for display in Peale's museum, in the same way I might have to reconstruct a broken statue using a support system. Peale drilled long holes through each piece of bone and used a hidden iron armature to assemble the skeleton. While we don’t drill into the bones anymore, Peale’s method was strong and elegant, and the armature is still supporting the mastodon today.

What are the materials?

Peale still had an incomplete skeleton and had to make decisions about the missing parts. He chose to have the missing bones carved in wood, in a style that made the replacement parts distinguishable from the original bones.

This realization stopped me in my tracks. This is a modern conservation concept, very atypical for the 1800s. In the eighteenth and ninteenth centuries, sculptors were often asked to restore and remake missing parts of sculptures so the damages weren’t noticeable. Today, we will still re-make missing parts of sculpture, but we use materials that are different and distinguishable from the original... just like Peale did over 200 years ago with this mastodon.

Peale’s son Rembrandt took charge of the replica wood bones, enlisting the help of Philadelphia sculptor William Rush and Moses Williams, a former enslaved person working at Peale’s museum. Bilateral symmetry and examples of bones from previous excavations allowed them to carve the shapes as scientifically accurate as possible at the time.

From ten feet away, the mastodon looks complete. However, from one foot away, the replica parts stand out like wooden sculptures. They suggest, but do not imitate bone. They’re beautiful. C- and V-shaped chisel marks dot the edges of the pelvis, right femur, and lower jaw to match the rough texture of real bone, but without hiding the woodcarver’s chisel. I’ve run a strong magnet along the wooden edges but nothing magnetic was detected. If nails were used, they’re buried quite deep suggesting the use of wooden pegs instead. SAAM’s Frames Conservator Martin Kotler used a piece of cherry wood and two carving chisels to replicate the marks seen on these wooden bones.

A Brief Return to America and More Mysteries

The mastodon left America in 1847 and has been in the collection of the Hessisches Landesmuseusm Darmstadt in Germany since 1854. In preparation to loan the mastodon back to America for the first time in 172 years, the Landesmuseum began cleaning the bones and wood. As their preparators cleaned the skeleton and removed a modern paint layer, they revealed another mystery underneath—old painted numbers and letters on the feet and ribcage! These must have been used to assemble and dissemble the skeleton during travel but what part of the mastodon’s mysterious history are these from?

Another interesting detail emerged after cleaning—a faux painted layer on the wooden replica ribs. This sturdy paint layer is probably oil paint and looks like imitation bone, perhaps painted to unify the wooden ribs with the mastodon bone. Charles Willson Peale was first and foremost a painter, could these be his brushstrokes from 1801?

My role as a sculpture conservator is often to understand an artwork’s materials and history, how these have changed over time, and what they tell us about the object. This mastodon once represented the pinnacle of scientific exploration and the Founding Fathers’ ambitions to prove the United States could compete with the history and wonder of Europe. Two centuries later, the skeleton as a sculpture can teach us even more about the era when it was discovered... and there are still mysteries to solve.

Watch the time-lapse video of the mastodon being installed at SAAM.

Can't get enough of the mastodon? Neither can we. Learn everything you wanted to know about mastodons with Paleontologist Advait Mahesh Jukar in our blog post "Hips Don't Lie: The American Incognitum."

To learn more about Humboldt, his influence on art and culture in the United States, and mastodons, watch SAAM Senior Curator Eleanor Harvey’s tour of the exhibition Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture, which has not yet opened to the public as part of the Smithsonian’s efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19. Our sister museum (also temporarily closed), the National Museum of Natural History is a great place for further discovery of mastodons, elephants, woolly mammoths, and yes, even beloved dinosaurs.