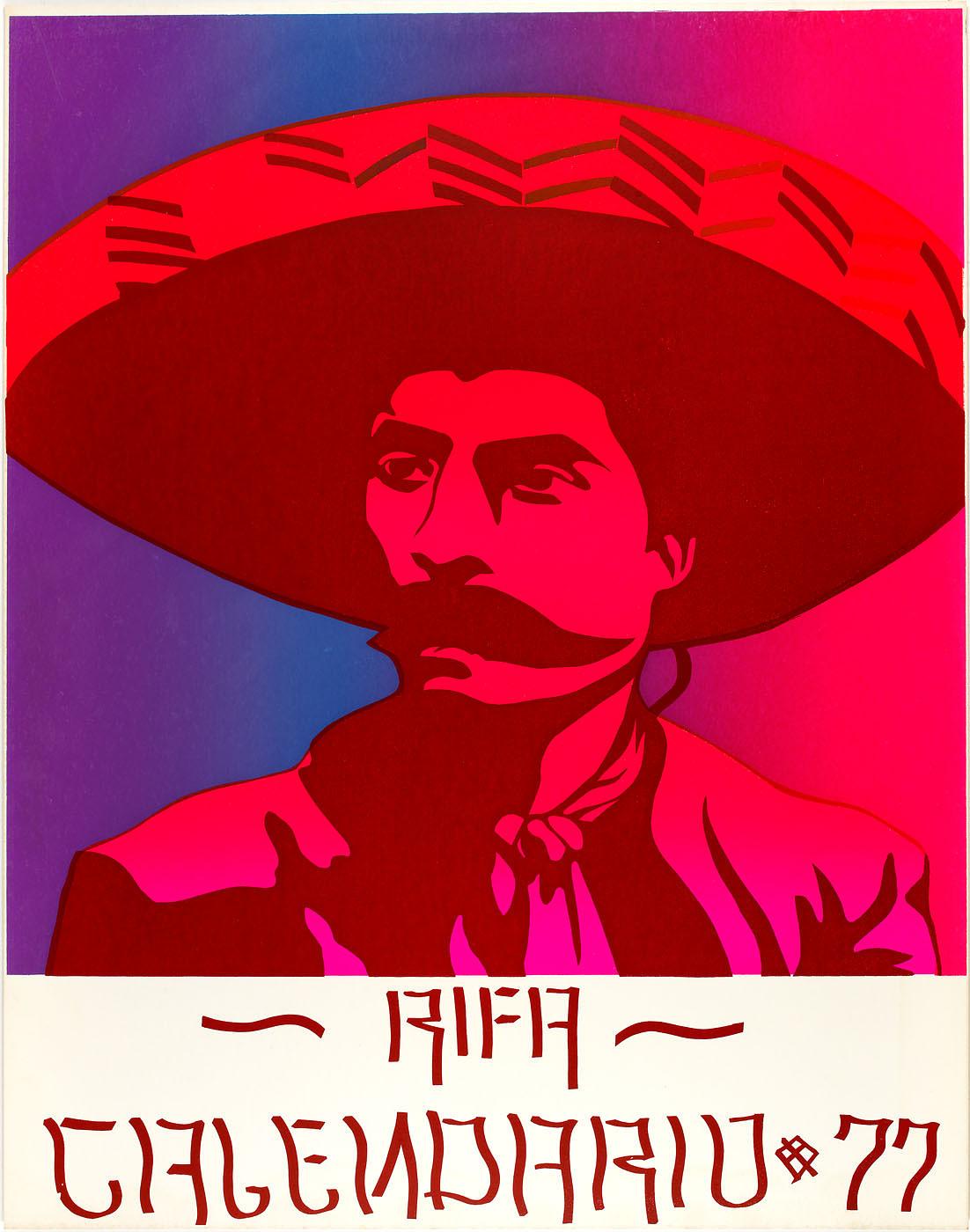

For his 1976 print RIFA, from Méchicano 1977 Calendario, Leonard Castellanos created a psychedelic-hued portrait of the iconic Mexican leader Emiliano Zapata, who fought for the land rights of working people and led an armed group of poor peasants known as “the Zapatistas” during the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920). Chicano artists saw themselves as continuing Zapata’s legacy of resistance efforts for land and Indigenous rights. Beneath the portrait, the artist includes the Chicano slang phrase, rifa, which means “we are the best.” This boastful reference is prevalent among early Chicano arts iconography.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Castellanos became influential as an artist and community organizer as the director and printmaker for the Méchicano Art Center in East Los Angeles. There, he trained artists to lead community workshops in screenprinting, supergraphics (decorative surface painting and murals), and poster making. At the Méchicano, Castellanos adopted the calendar format for prints, as was being done at other Chicano organizations and collectives such as the Royal Chicano Air Force (RCAF).

Art historian Terezita Romo describes the importance of the calendar format in her essay in the ¡Printing the Revolution! catalogue. Many Chicanos grew up with illustrated Mexican-themed calendars hanging in their homes, often giveaways from local businesses. They offered artists the ability to reach the widest audience possible by providing a familiar and functional format for graphics while also pushing artistic boundaries. By utilizing a medium that people relied upon in their daily lives, calendars became an essential fundraising tool as well as an opportunity for artists to convey messages to their community.

Romo describes Méchicano’s 1977 calendar as reflecting an “aesthetic spectrum of the sociopolitical interests and artistic styles of each participating artist, many of whom were not printmakers…Chicana/o artists revised its single image format, offset medium, and commercial objective.” Beyond their role as a product to raise money, they were a means of educating the community about Chicano culture and history.

SAAM’s landmark exhibition, ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now, explores how Chicanx artists have linked innovative printmaking practices with social justice. This blog post is part of series that takes a closer look at selected artworks with material drawn from exhibition texts and the catalogue.