This comic is part of a series Drawn to Art: Ten Tales of Inspiring Women Artists that illuminates the stories of ten women artists in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Inspired by graphic novels, these short takes on artists’ lives were each drawn by a woman student-illustrator from the Ringling College of Art and Design.

Corita Kent joined a religious order after high school and became fascinated with screen printing. She would go on to be described as “the pop art nun who combined the sensibility of Andy Warhol with social justice,” and helped to bring a little more color to the world.

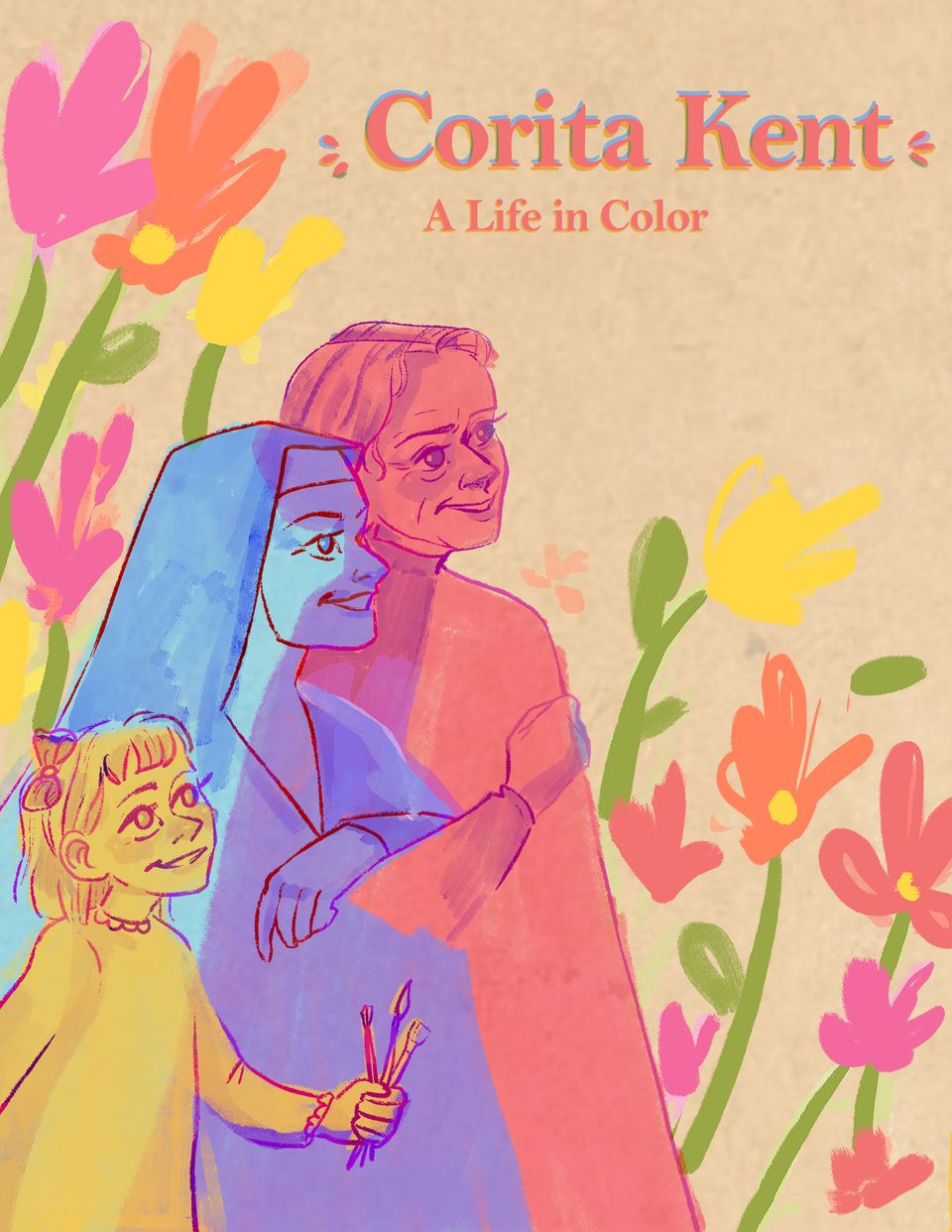

Comic book cover is a colorful illustration of a young girl, woman, and old woman standing together under the words, “Corita Kent: A Life in Color.” The young girl is entirely depicted in yellow. Her hair is in a bob, and a barrette holds it away from her face, and her dress is edged in lace at the collar and cuffs of the long sleeves. She is holding paintbrushes in her left hand. Next to her, a woman wearing a nun’s habit is depicted in blue in purple. The older woman stands next to her, and is all in red. Her hair is pulled away from her face. They are all smiling and looking into the distance. Around the three figures, yellow, orange, and pink flowers are illustrated. They represent the three stages of Corita Kent’s life.

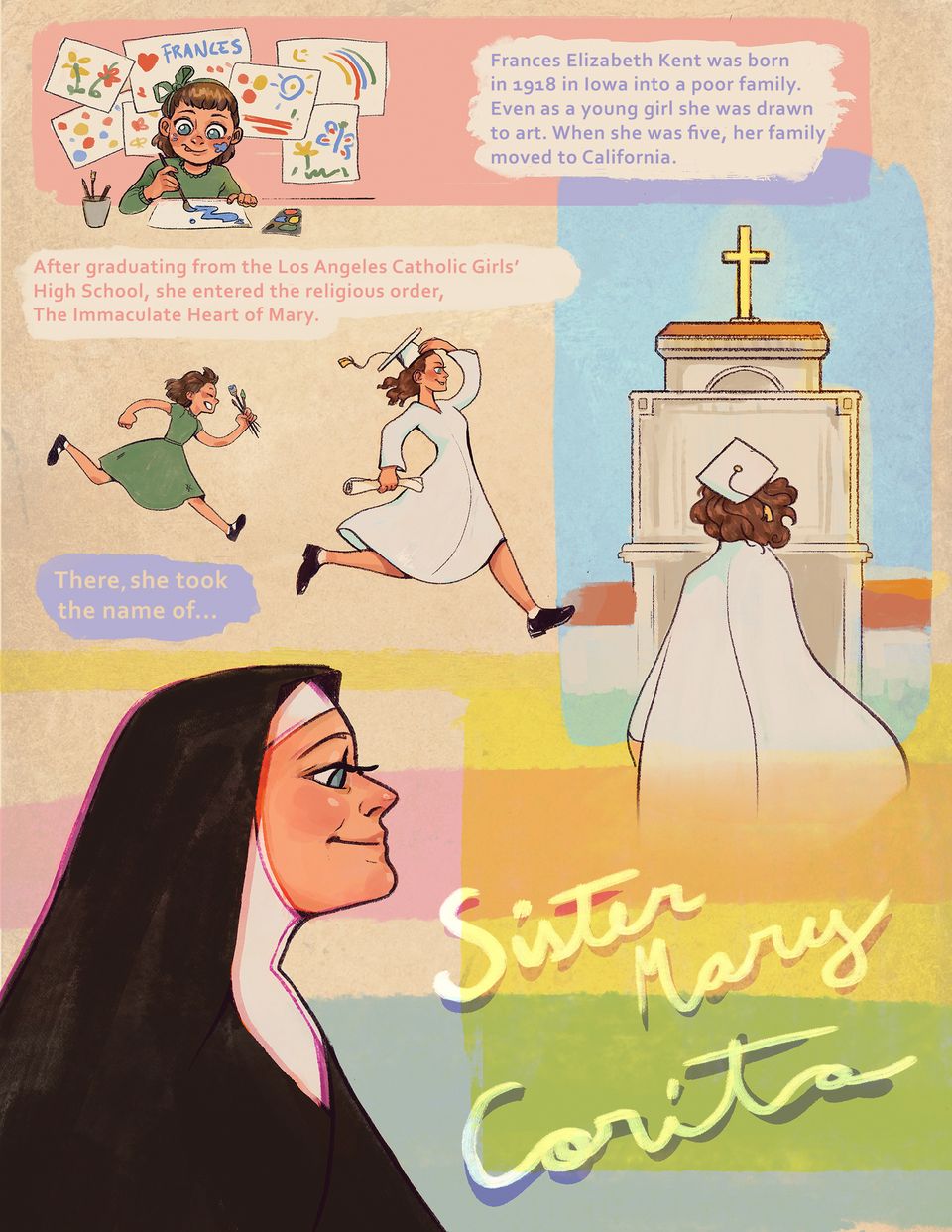

A young girl wearing a dress with a ruffled collar and long sleeves with ruffled cuffs sits at a table, painting with watercolors. She is the artist Corita Kent. She wears her hair in a short brown bob with bangs, a green bow tied at the top of her head. Her face is splattered with paint. Her expression is one of intense concentration with her tongue sticking out one side of her mouth. Behind her, across the top of the page, a wash of pale pink, as if a layer of watercolor paint brushed across the paper. Text reads, “Frances Elizabeth Kent was born in 1918 in Iowa into a poor family. Even as a young girl, she was drawn to art. When she was five, her family moved to California.” Mary Elizabeth, wearing a green dress, patent-leather shoes, and white ankle socks, runs across the center of the page. She is clutching three paintbrushes in her left hand, and her face is gleeful. She’s trailing behind a teenaged Mary Elizabeth, who strides ahead, longer brown hair streaming behind her. She is wearing a white graduation cap and gown and black brogues with white ankle socks, her left hand holding the cap on her head, her right clutching a scroll of paper, a high school diploma. Text reads: “After graduating from the Los Angeles Catholic Girls’ High School, she entered the religious order, The Immaculate Heart of Mary. There, she took the name of... Sister Mary Corita.” The right side of the page is washed in a strip of light blue, framing a kneeling Mary Elizabeth, her curled brown hair waving, still wearing her cap and gown and kneeling in front of a tall white altar and gold cross. The bottom of the page is washed in multicolored swaths of rainbow colors, framing the profile of Sister Mary Corita wearing the black and white head covering of a Catholic sister. She looks to the right, in profile, a soft smile on her face, in front of her is written in large loopy text, her chosen name: Sister Mary Corita.

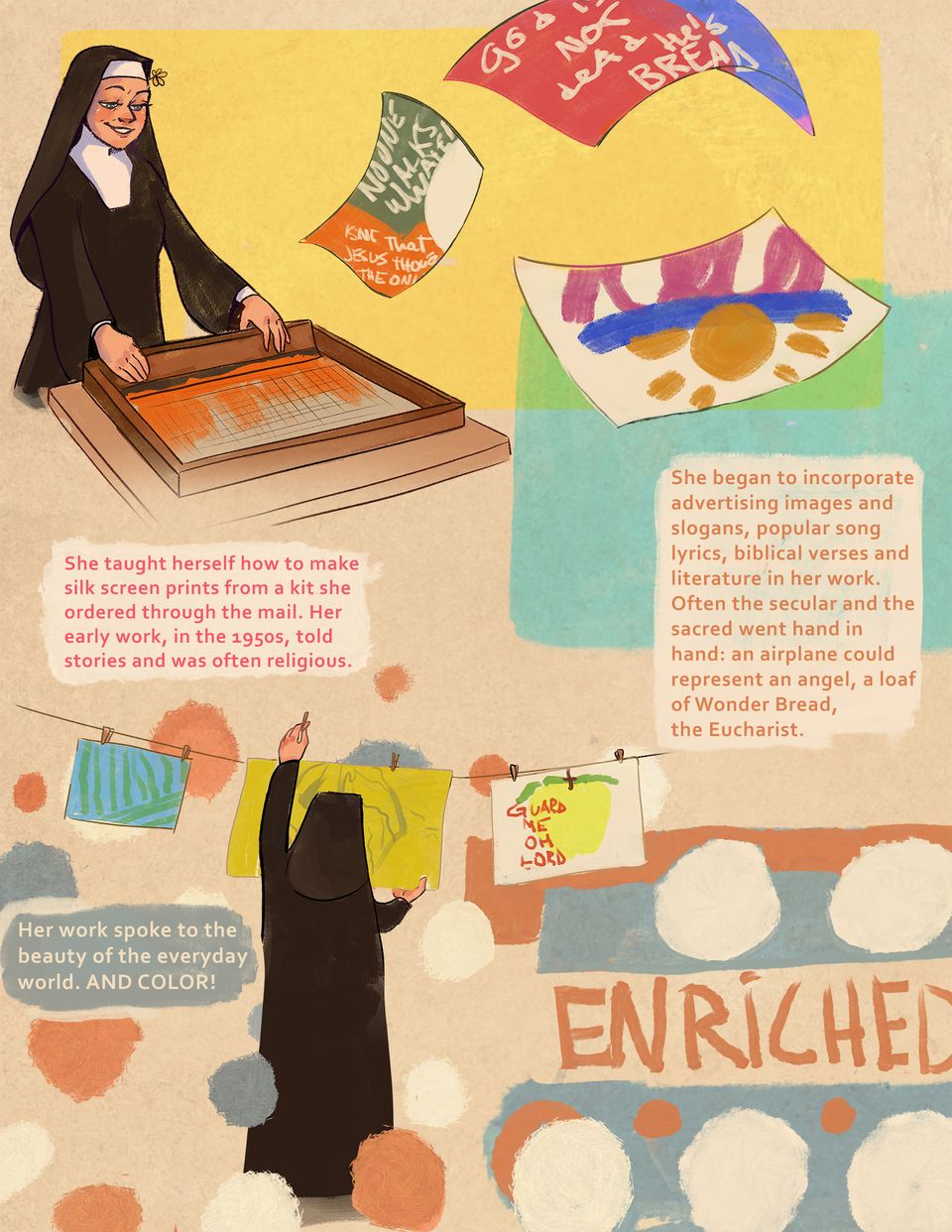

Against a wash of yellow color, Sister Corita stands at a table in front of a silk screen frame. She smiles softly, her cheeks rosy against the black and white of her habit and veil. A cheerful daisy hints at an independent and beauty-loving soul. She is pulling the squeegee across the silkscreen, spreading orange pigment onto the paper below. Finished prints float off into the air to the right, across the top of the page. The first, bold blocks of orange, green, and white, includes incomplete phrases from Corita Kent artworks, “NO ONE WALKS WATERS. ISNT THAT JESUS THOUGH THE ONLY” and the next, against red and blue, reads, “GOD IS NOT DEAD HE’S BREAD.” The last shows a bright yellow sun and blue and pink squiggles. Text reads, “She taught herself how to make silk screen prints from a kit she ordered through the mail. Her early work, in the 1950s, told stories and was often religious. She began to incorporate advertising images and slogans, popular song lyrics, biblical verses and literature in her work. Often the secular and the sacred went hand in hand: an airplane could represent an angel, a loaf of Wonder Bread, the Eucharist.” Across the bottom, the scene shows a clothesline stretches across the width of the page. Amid pale red and blue and white dots, like paint splotches, Corita stands with her back to the viewer, reaching up to hang prints on the line with clothespins. To her left is a green-and-blue print. She is affixing the second clothespin to a yellow print and to her right, a print of a yellow fruit with green leaves reads, “GUARD ME OH LORD.” Text reads, “Her work spoke to the beauty of the everyday world. AND COLOR!” In the bottom right corner of the page, the word “ENRICHED” is printed in pale red in the style of the Wonder Bread logo. The dots floating around Corita are in the same colors, bringing to mind the polka dots on the Wonder Bread bag.

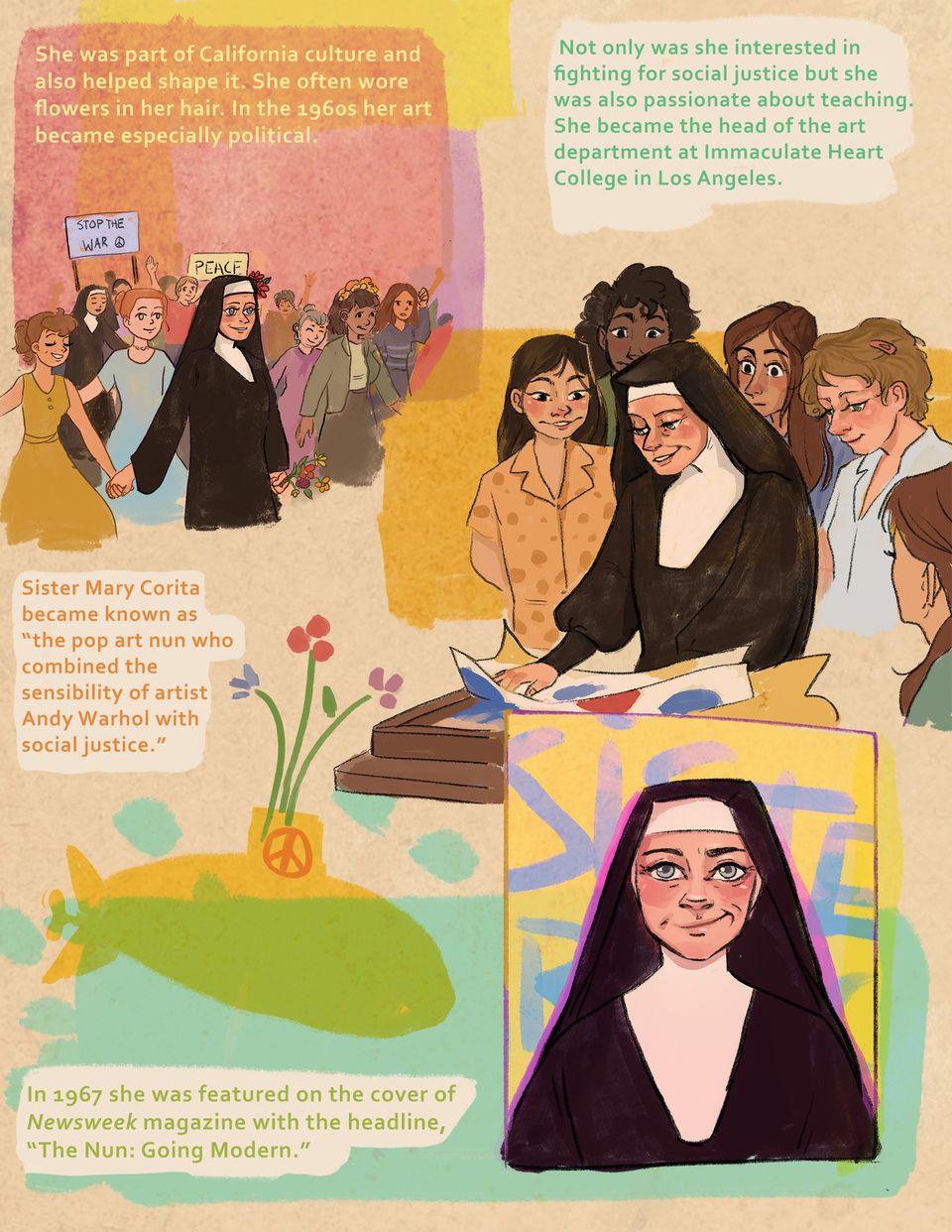

Across a wash of pink and yellow and purple on the top left of the page, text reads, “She was part of California culture and also helped shape it. She often wore flowers in her hair. In the 1960s, her art became especially political.” Below, Sister Corita stands, wearing her nun’s habit and veil, flowers tucked behind her ear. In her left hand, she holds a bunch of wildflowers, and in her right, she holds a young woman’s hand. She is standing among a group of women of all colors, some old, some young, some nuns, some holding protest signs that read “STOP THE WAR” and “PEACE.” At the top right of the page, text reads, “Not only was she interested in fighting for social justice, but she was also passionate about teaching. She became the head of the art department at Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles.” Below, against a wash of yellow, Sister Corita, wearing her black and white habit and veil, stands in front of a table covered in bright paper. She is surrounded by four young women, all gaze at the artwork in front of them. They are her students, and they are clustered around her to learn from their teacher. The young Asian woman to her right has long dark brown hair framing her face and dark brown eyes. She has an expression of admiration on her face, her arms tucked behind her back, almost in anticipation. To the right, a young Black woman with softly curling dark brown hair gazes with interested eyes. A serious-looking young woman with brown skin and rosy cheeks face framed in long straight brown hair. The woman to the right of her has short wavy blonde hair pulled back from her pink-cheeked face, a soft smile of concentration. A young woman is seen in profile. Her brown hair pulled back from her face in a long ponytail. Text reads, “Sister Mary Corita became known as ‘the pop art nun who combined the sensibility of artist Andy Warhol with social justice.’” In the last panel that stretches across the bottom of the page, a yellow submarine with wildflowers coming out of the top and a peace sign painted on it floats in a blue sea on the left side of the page. On the right, the nun again in her black and white habit and veil, is shown smiling on the cover of a magazine. Text reads, “In 1967 she was featured on the cover of Newsweek magazine with the headline, ‘The Nun: Going Modern.’”

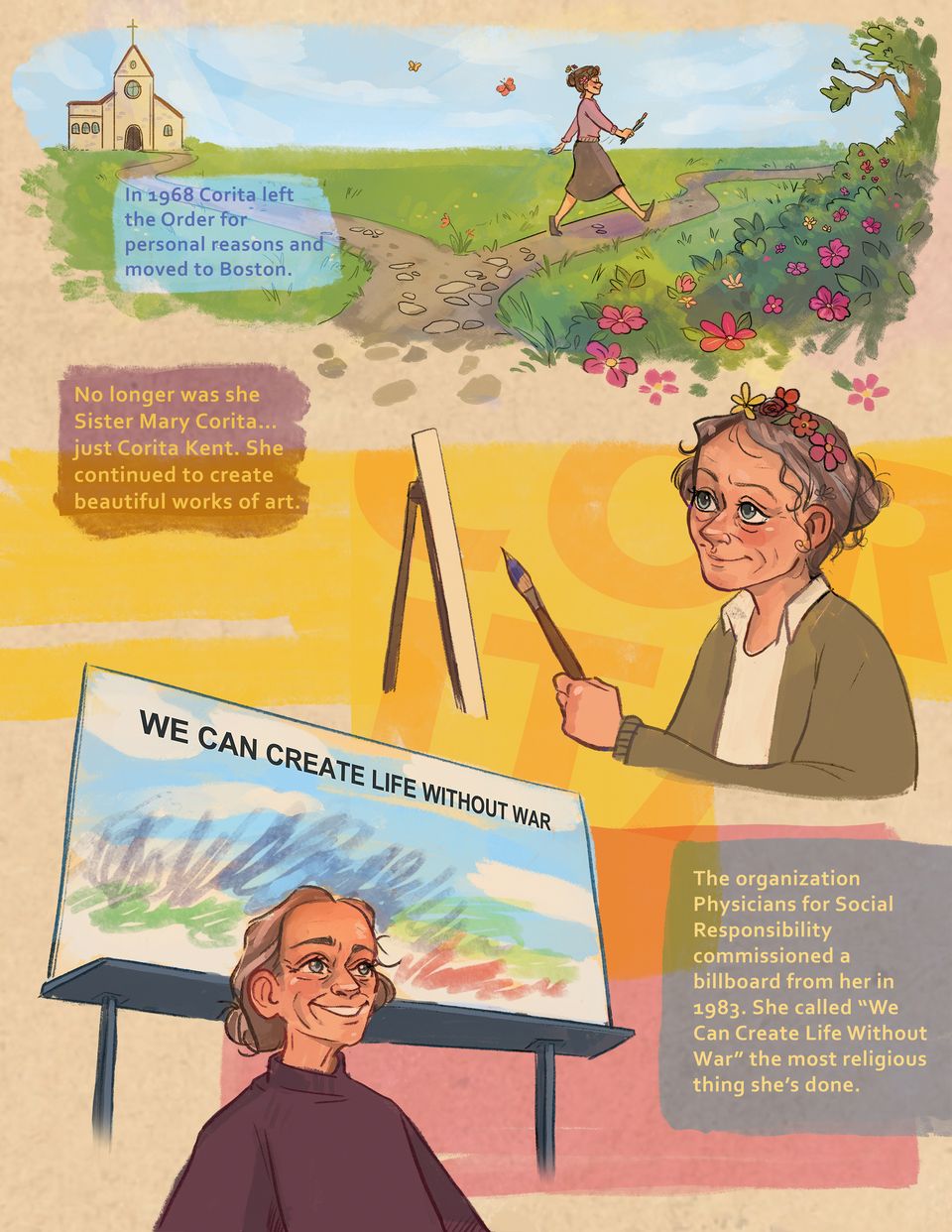

Across the top of the page is an idyllic country scene, almost as if out of an animated children’s movie. To the left, a small white church with a gold cross sits against a blue sky, green grass studded with pink wildflowers stretch off to the right. Orange and yellow butterflies fly through the blue sky as if trailing behind Corita, who strides down a country dirt path, clutching paintbrushes. No longer is she wearing her long black and white habit and veil. Instead, she wears a brown sweater and long brown skirt, sensible brown shoes on her feet, graying hair pulled away from her face and into a bun decorated with flowers. Text reads: “In 1968 Corita left the Order for personal reasons and moved to Boston.” In the center of the page, below the country scene, a wash of yellow with darker yellow letters frames Corita, who looks a little older, her expression calm and interested. She is in front of an easel, and a brush is poised as if to start painting. Her hair, streaked with grey, has flowers in it. Text reads: “No longer was she Sister Mary Corita... Just Corita Kent. She continued to create beautiful works of art.” On the bottom third of the page, a large billboard looms, proclaiming, “WE CAN CREATE LIFE WITHOUT WAR.” Corita stands below it, proudly beaming. She is noticeably older, hinted by her gray hair and lines on her face. Text reads, “The organization Physicians for Social Responsibility commissioned a billboard from her in 1983. She called “We Can Create Life Without War” the most religious thing she’s done.”

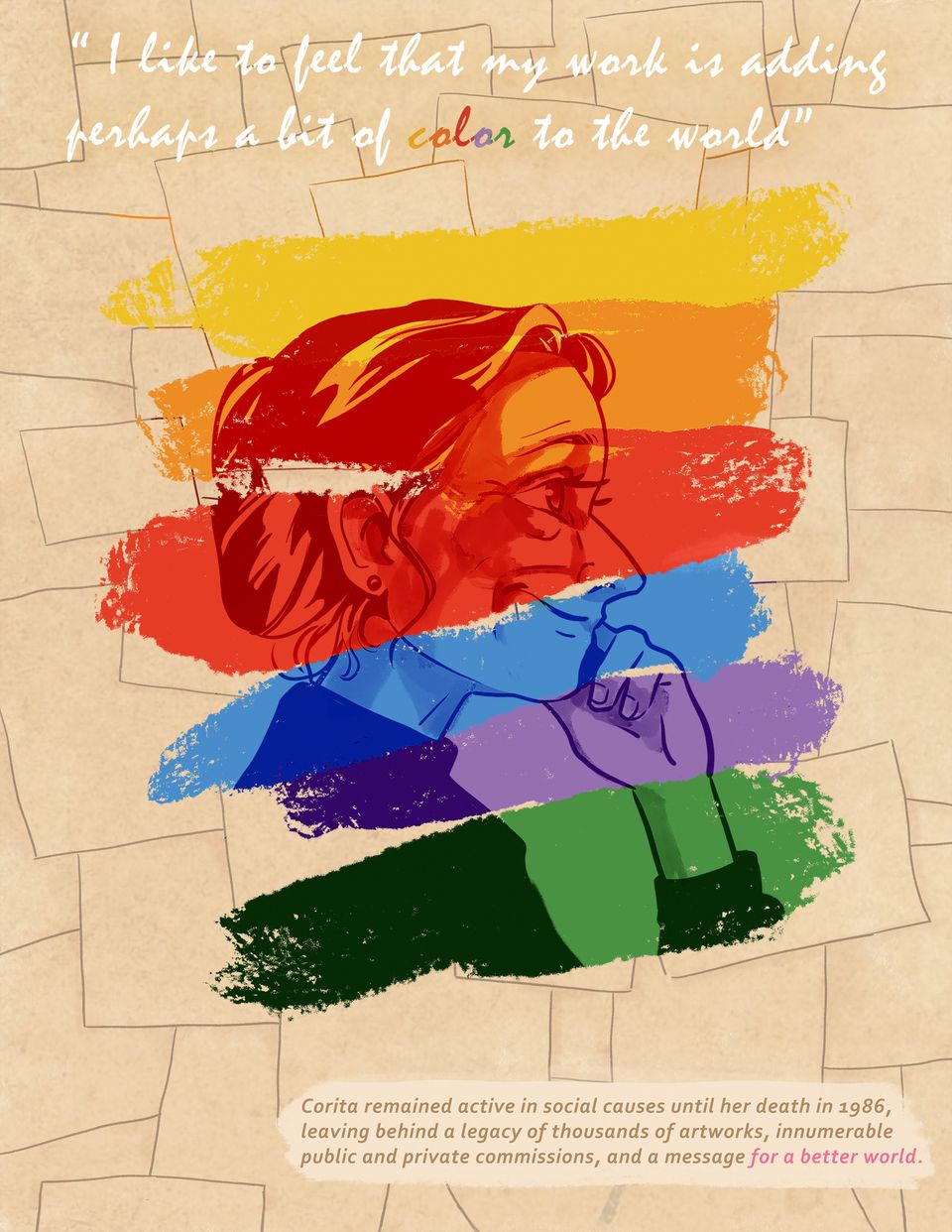

White script across the top of the page reads, “I like to feel that my work is adding perhaps a bit of color to the world.” The word “color” is not white, but each letter is a different color of the rainbow: yellow, orange, red, purple, green. The page is decorated with squares as if overlapping pieces of paper. The colors of the rainbow are depicted in wide swaths as if painted by a brush. They highlight Corita’s head in profile. She is gazing off into the future, with her hand on her chin and her gaze in contemplation and a soft smile on her face. Text reads, “Corita remained active in social causes until her death in 1986, leaving behind a legacy of thousands of artworks, innumerable public and private commissions, and a message for a better world.” All the text is beige, but “for a better world” is pink.

Swatches of colors of the rainbow, as if painted by a brush, cross the center of the page. Text reads, “Illustrated by Mica Borovinksy”