Allison Carey, currently an Advanced Level Intern at SAAM, graduated from Dartmouth College in 2020, where she studied the intersection of American art and movements for equality. In the fall she will begin her studies at the Institute of Fine Arts at NYU, pursuing her Masters in the History of Art.

Over the past six months as an Advanced Level Intern at SAAM, I have been engaged in a deep dive into the women artists represented in the museum’s collection. This experience has introduced me to strong, fiercely independent women; women who pushed against the status quo not only through their incredible artistic output, but also through the very act of creating art. In a world where the most recognizable and successful artists are still predominantly white men, these women powerfully challenged that assumption.

As I explored the lives of these changemakers, I asked myself: after years of studying art and art history, why was I only just now learning about some of these important women? Their art opens up crucial historic narratives—narratives that not only communicate a history of art and aesthetics, but also convey important, repeatedly omitted perspectives on the American story.

The project I am working on is ultimately translating these artists' stories into short webcomics, created by rising women illustrators at the Ringling College of Art and Design. Perhaps one day, when a young person opens up a book on the history of art, walks into a gallery space, or simply searches on the internet “famous artists,” the first thing they will see is the name and work of one of these strong, women changemakers staring back at them.

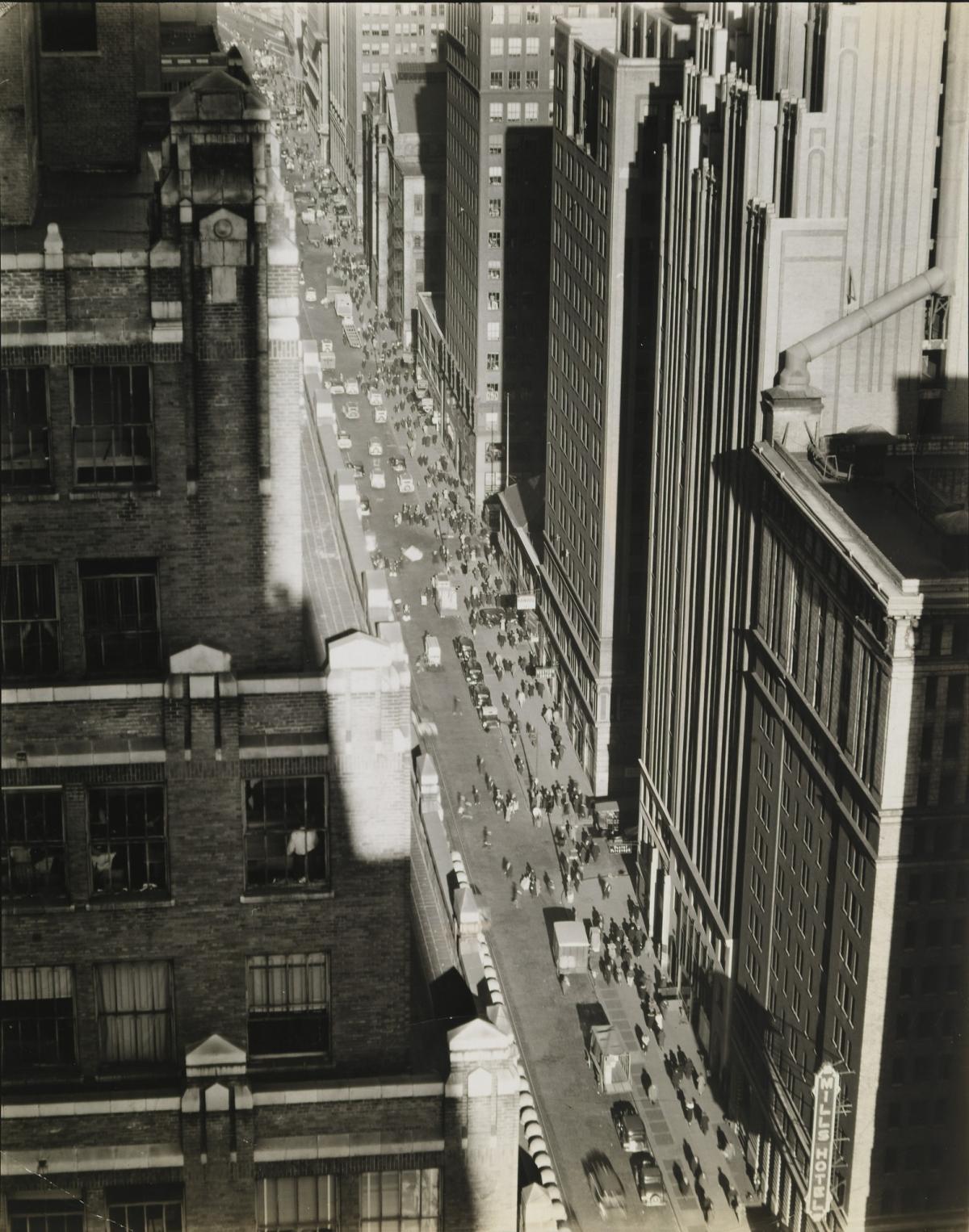

Berenice Abbott

In a time when photography was primarily understood as simply a means of documentation, Berenice Abbott claimed it could be art.

After moving to Paris in her early twenties, Abbott’s serendipitous encounter with her friend, Surrealist artist Man Ray, led to her working in his dark room where she learned to develop film and print photographs. She eventually opened her own studio where she refined her own creative approach to image making.

In her own words, Abbott believed that, “A photograph is not a painting, a poem, a symphony, a dance. It is not just a pretty picture, not an exercise in contortionist techniques and sheer print quality. It is or should be a significant document, a penetrating statement, which can be described in a very simple term—selectivity.”

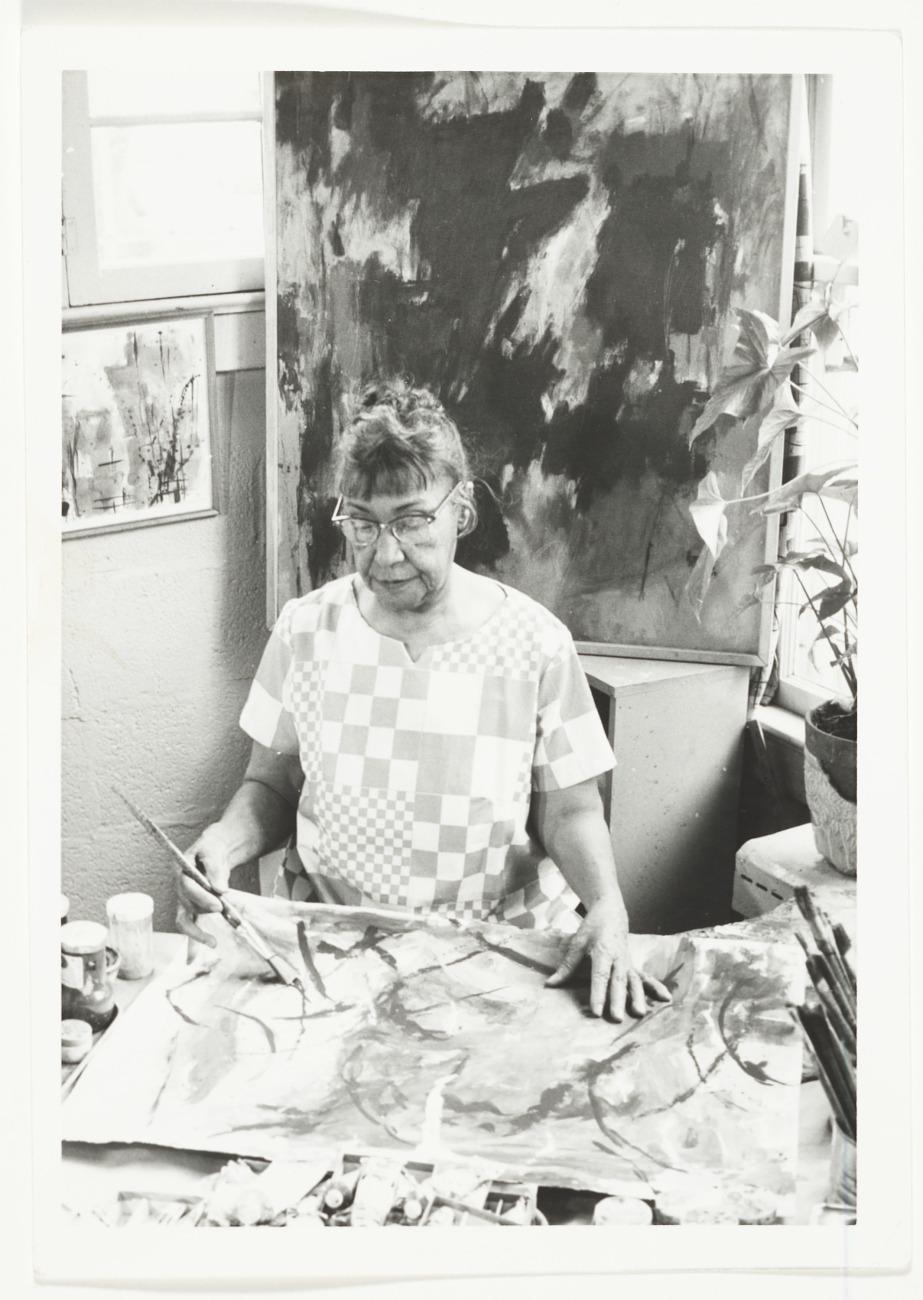

Kay Sekimachi

While most people saw textiles as functional materials for utilitarian objects, Kay Sekimachi explored the potential to create sculptural, three dimensional forms out of fibers and fabric.

Sekimachi was born in Northern California to two Japanese immigrants. Her childhood in Berkeley was not easy; her father died at a young age, her mother was poor, and she spent a few years of her youth living in an incarceration camp for Japanese citizens following the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Later in life, when Sekimachi attended California College of Arts and Crafts, a friend introduced her to the weaving room. Fascinated by the sight of the loomers at work, Sekimachi immediately decided to spend all of her savings on a loom. She would soon push the limits of what weaving could produce, creating sculptural forms out of textiles and ultimately resurrecting the medium as a form of art. Sekimachi’s incredible ingenuity behind the loom earned her the respected title of the “weaver’s weaver.”

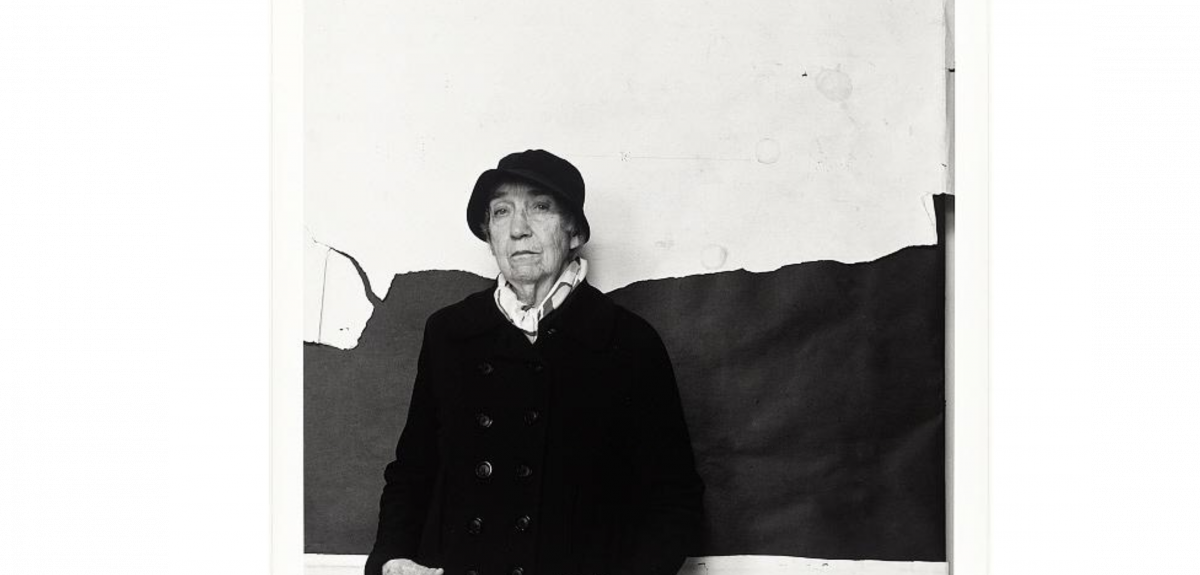

Carmen Herrera

Carmen Herrera is a groundbreaking artist whose hard-edged abstractions were unparalleled at the time of their conception in the late 1940s. However, it wasn’t until Herrera turned 93 that her work began gaining the attention it deserved. Her first major solo show in New York City occurred when Herrera was nearly 101 years old.

Herrera was born in Havana, Cuba where she studied architecture in her early years. When she immigrated to New York City in her young 20s, she shifted her focus to painting. Eventually, Herrera moved to Paris, where she was inspired to develop an entirely abstracted, minimalist style of work—nearly a decade before the rise of the minimalist movement. Herrera explains that she “began a lifetime process of purification, a process of taking away what isn’t essential.”

Hererra’s position as both a woman and an immigrant led to her often overt discrimination from the art world. Yet, nonetheless, Herrera continued producing art until, finally, she began gaining the recognition in her ninth decade of life. Today, at the age of 105, she continues to create artwork, stating “I believe that I will always be in awe of the straight line, its beauty is what keeps me painting."

Edmonia Lewis

Edmonia Lewis was the first professional African American sculptor. Yet, Lewis refused to be limited or defined by this identity. As she stated, “Some praise me because I am a colored girl, and I don’t want that kind of praise. I had rather you would point out my defects, for that will teach me something.”

Lewis was born in 1844 to a Caribbean, (particularly Haitian) father and a Native American, Chippewa mother. In her early twenties Lewis moved to Massachusetts where she met the renowned sculptor Edward Brackett, with whom she began studying sculpture.

Lewis eventually relocated to Rome where she further studied and mastered sculpture. The artistic freedom Rome offered Edmonia as a woman of color allowed her to develop an impressive neoclassical practice. She celebrated her dual African American and Native American ancestry by creating portrait busts of celebrated abolitionists and figural work dealing with narratives that reflect minority experiences. Many of these very works are now SAAM’s collection, continuing to serve as a source of inspiration to this day.

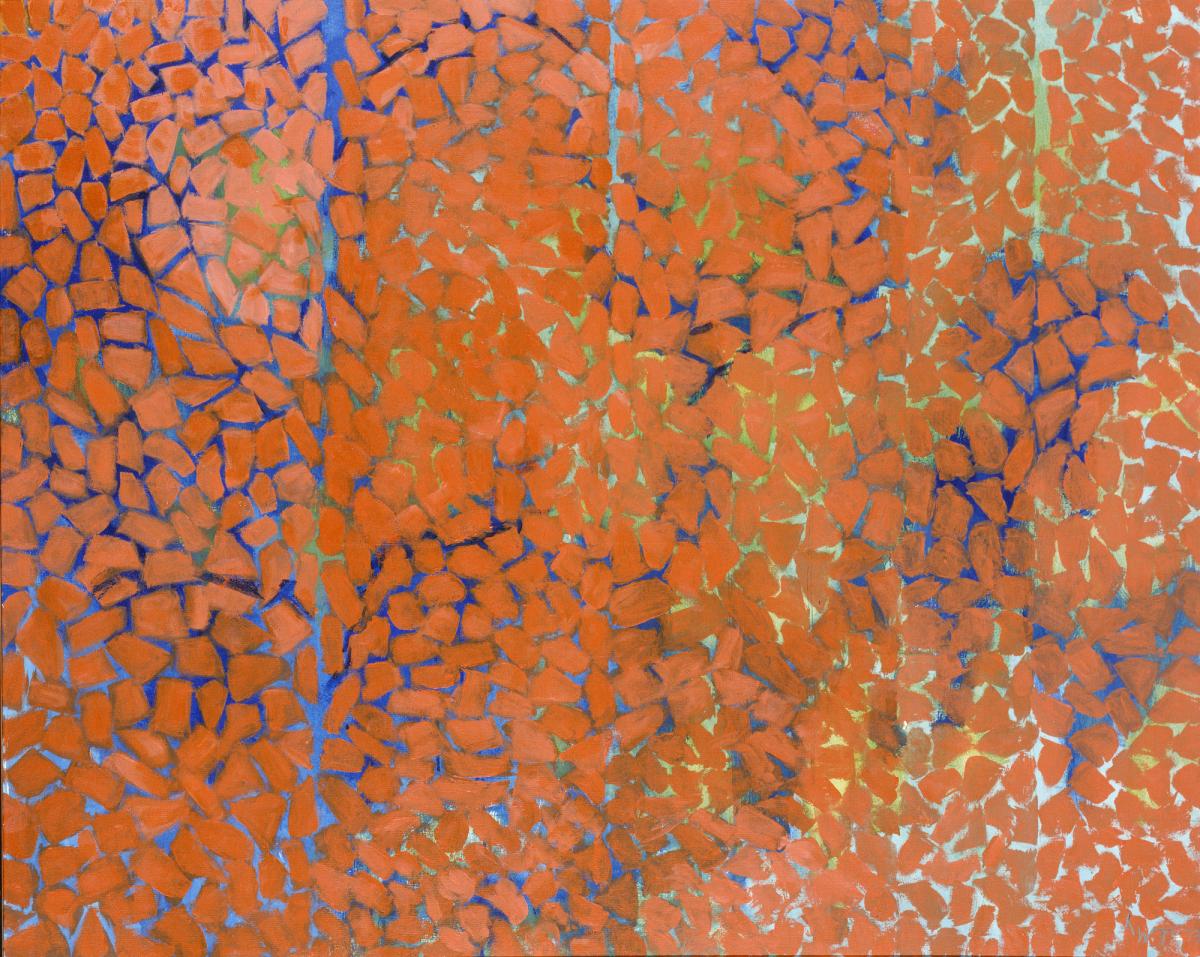

Alma Thomas

Alma Thomas was an exuberant colorist whose abstractions are grounded in the forms and colors of the natural world.

Thomas did not dedicate her career to art until the 1960s, in her seventh decade of life. Yet art was at the core of Thomas’s experience since her early years. Thomas, who moved to DC when she was 16 years old, was the first graduate from Howard University’s fine arts program– and the first Black woman to earn an arts degree. At the height of the Civil Rights movement, Thomas’s work focused purely on the wonder and sublime quality of the natural world. As she explained, “Man’s highest inspirations come from nature. A world without color would seem dead. Color is life. Light is the mother of color. Light reveals to us the spirit and the living soul of the world through colors.”