SAAM’s landmark exhibition, ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now, explores how Chicanx artists have linked innovative printmaking practices with social justice. In the second of a two-part conversation join E. Carmen Ramos, exhibition curator and acting chief curator at SAAM, and Claudia Zapata, curatorial assistant for Latinx art, as they discuss the origins and importance of the exhibition. The first part of the conversation is here: Chicano Graphic Arts and the Making of the Landmark Exhibition "¡Printing the Revolution!"

Claudia, can you elaborate on our use of the term “graphics” throughout the exhibition?

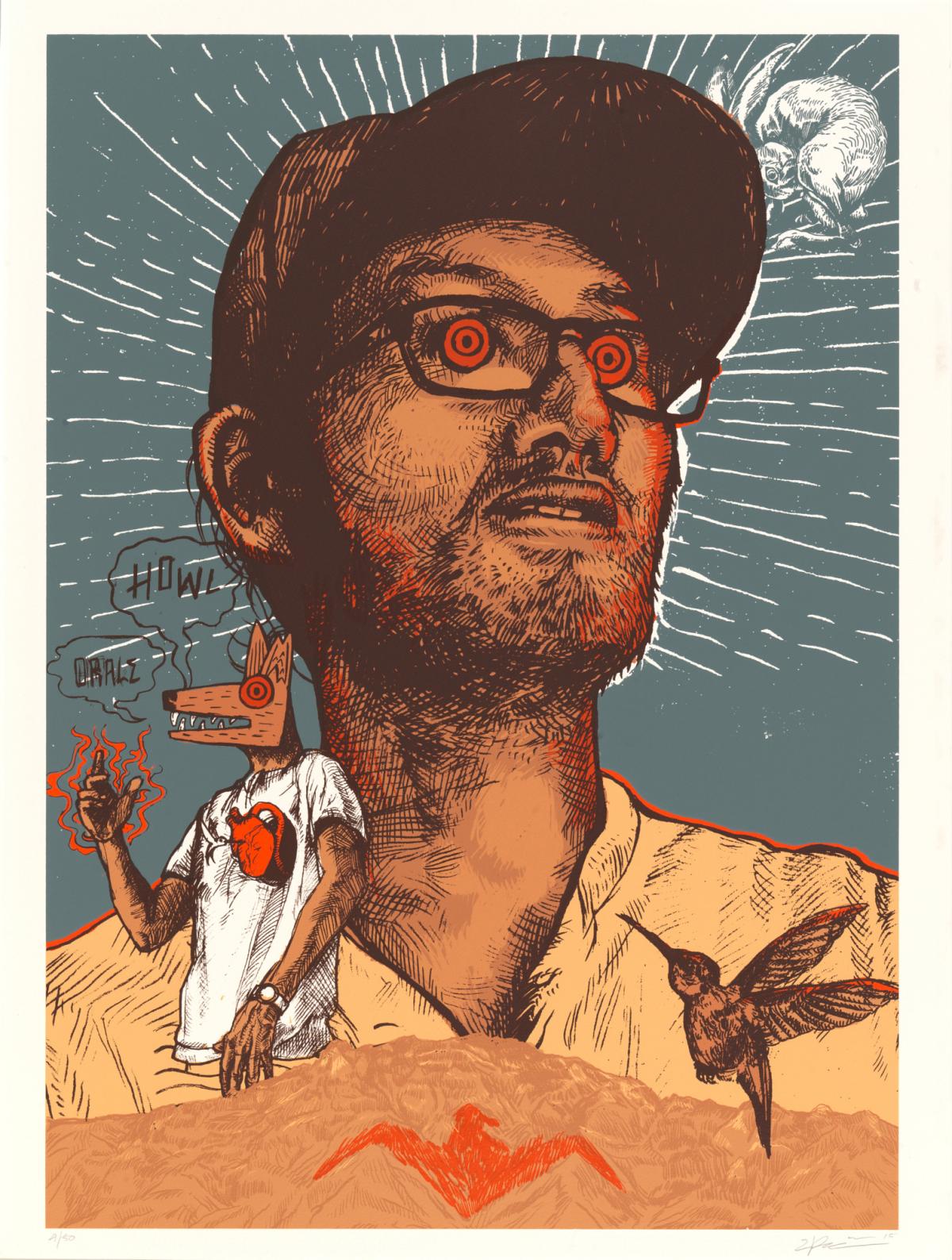

The most interesting aspect of Chicanx graphics is its malleability as a concept. In the realm of Chicanx art, graphics usually cites printmaking, especially works created using the screenprinting process. A large portion of works in ¡Printing the Revolution! are screenprints, but we do recognize artists’ experimentation in three-dimensional creations, public interventions, zines, and other digital graphics. So, we’re expanding the definition and look of a Chicanx graphic art show to highlight the diversity of contemporary artists’ creations. There are certain definable characteristics associated with an official fine art print, for example: editioning the print, a studio chop (if made at a printing center), a signature, and year inscription. Yet, several works in the exhibition do not fall within these parameters. Some were made quickly for immediate use in protests, like Emanuel Martinez’s Tierra o Muerte, which is a screenprint on a manila folder that was used to support the Reies López Tijerina land rights cause. We have also acquired digital works in JPG, PDF, and TIFF file formats. Artists working in the digital realm use their personal websites and social media networks to disperse their social justice images. Often born-digital works never exist on paper but are primarily exchanged via the internet to immediately advocate and take part in online dialogues. Featured works by Xico González and Zeke Peña have AR (augmented reality) components. Using mobile apps, viewers can see overlaid animations and video, with the print acting as the designated marker. The act of viewing and the frame which defines this experience is ever changing with these new artistic methods, and ¡Printing the Revolution! takes the next step in acknowledging these digital contributions to Chicanx art history.

Carmen, 1965 is an important date for the study of Chicanx art. We cite this date in our title but also extend our frame of reference to today. What is the significance of this chronological framework?

We cannot overemphasize the importance of the 1960s as a turning point period for people of Mexican descent in the United States. The activism of César Chávez and Dolores Huerta, who founded the United Farm Workers union to combat the horrendous working conditions of California farmworkers, took on a very public dimension in 1965. Their activism galvanized people of Mexican descent in unprecedented ways. The start of the Chicano civil rights movement, or El Movimiento, marked a completely new way of being a person of Mexican descent in the United States. To call yourself Chicano — a formerly derogatory term for Mexican Americans — became a cultural and political badge of honor that expressly rejected the goal of melting-pot assimilation. It signaled a defiant challenge to the racial hierarchies of US society. This ethos shaped culture broadly defined, and the explosion of graphic arts is just one place where it was keenly felt.

Citing the date 1965 also meant to give our audience an anchor into what our exhibition is about. As a curator in Washington, DC, for now ten years, I am very aware that there are large populations that know little about Chicanx and Latinx art and culture. This is one of those instances where you can palpably see how our society is not structured to value non-white people. If it was, the general public would be familiar with elementary aspects of our history. We’re constantly looking for ways to give our visitors an entry point, and we believed that the date 1965 would signal that the works they are about to encounter have a connection to the tumultuous and transformational decade of the 1960s.

This is the second medium-specific show that I have organized at SAAM, and I didn’t set out to do that when I came here. I’m not a graphic arts specialist. But Chicano graphic arts during the civil rights era is such a foundational aspect of the history of Chicanx art, I felt it necessary to dig deeper into its legacy and show how graphics arts remain important, thriving, and dynamic today.

What does it mean to be presenting this exhibition during the COVID–19 pandemic and the public battle against systemic racism?

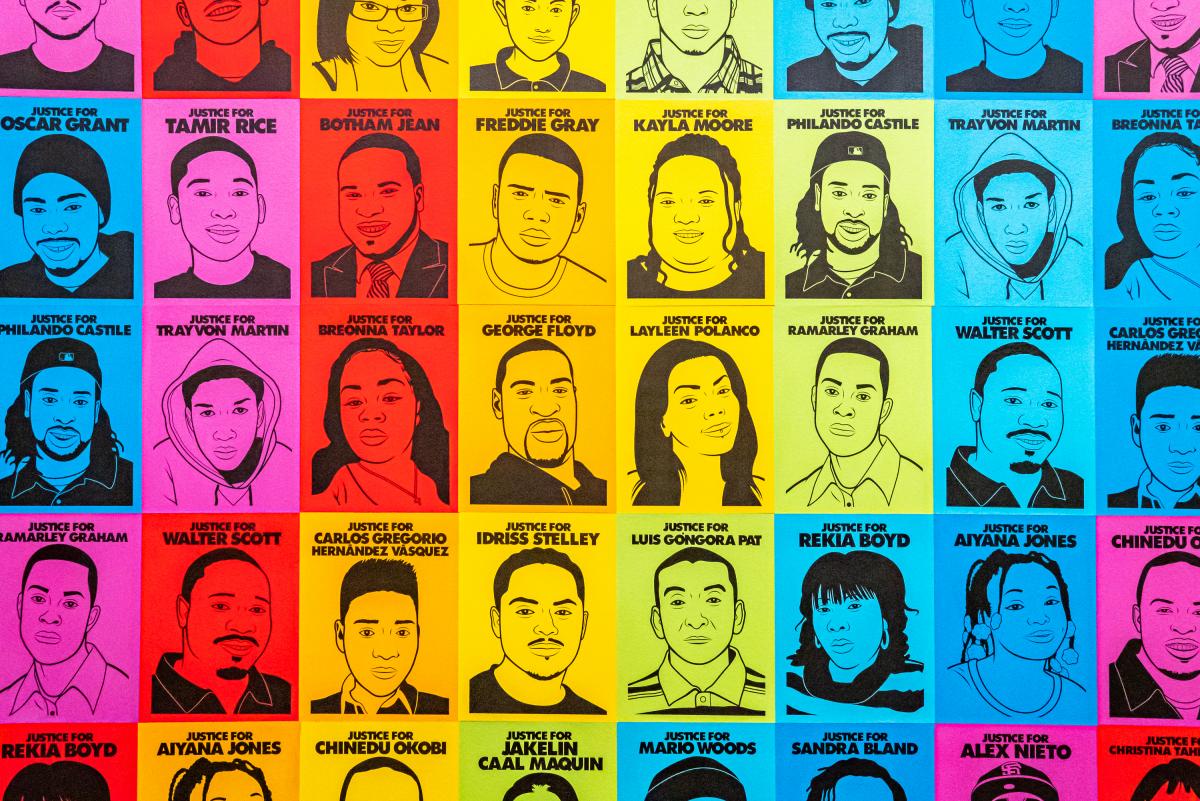

Carmen: We are living through unprecedented times of social, economic, and political crisis. This period will be remembered as being as transformative as 9/11. ¡Printing the Revolution! could not be better timed. Our double pandemic of a health and a social justice crisis has exacerbated the inequalities in our society around many of the issues the artists in the show have explored. An underlying thread of this exhibition is that we are still striving to create a more perfect union. ¡Printing the Revolution! is not an institutional response to current events; it was in the works for several years and stems from our commitment to educate audiences about Latinx art, and to value, preserve, and interpret these works. The artworks in this exhibition show us that the issues being debated in the museum field today have been at the center of BIPOC artists’ practice. From the beginning, Chicano artists and institutions prioritized reaching working-class and BIPOC audiences decades before community engagement was a museum goal and strategy. Artists used their art to challenge historical narratives that gloss over injustice and disregard the experiences of people of color. For example, a section of our exhibition shows how Chicanx artists and their cross-cultural collaborators used portraiture to highlight changemakers who fought against injustice around the world. They used a genre commonly associated with privilege and individuality to instead call attention to sacrifice and communal empowerment. The artists in this exhibition share strategies that audiences and cultural institutions can learn from.

Read part one of the conversation, Chicano Graphic Arts and the Making of the Landmark Exhibition ¡Printing the Revolution!, on SAAM’s blog. Additional images, videos, and commentary about artworks included in the exhibition are in our online gallery.