Follow the threads of Consuelo Jimenez Underwood’s fiber artworks and soon a message will become clear: this artist weaves together her heritage and personal experience to create personal reflections that encompass the lived experiences of communities navigating cultural identity and resilience, inviting viewers to delve into the ultimate complexity of connection and belonging. She stitches pain, history, and hope into richly nuanced personal narratives about immigration at the US-Mexico border. Her father was an undocumented fieldworker in California, and her family regularly crossed the border. Through her intricate textiles and evocative storytelling, she brings to light the struggles and triumphs of the immigrant journey.

This Hispanic Heritage Month, here are four ways to explore Underwood’s art and life.

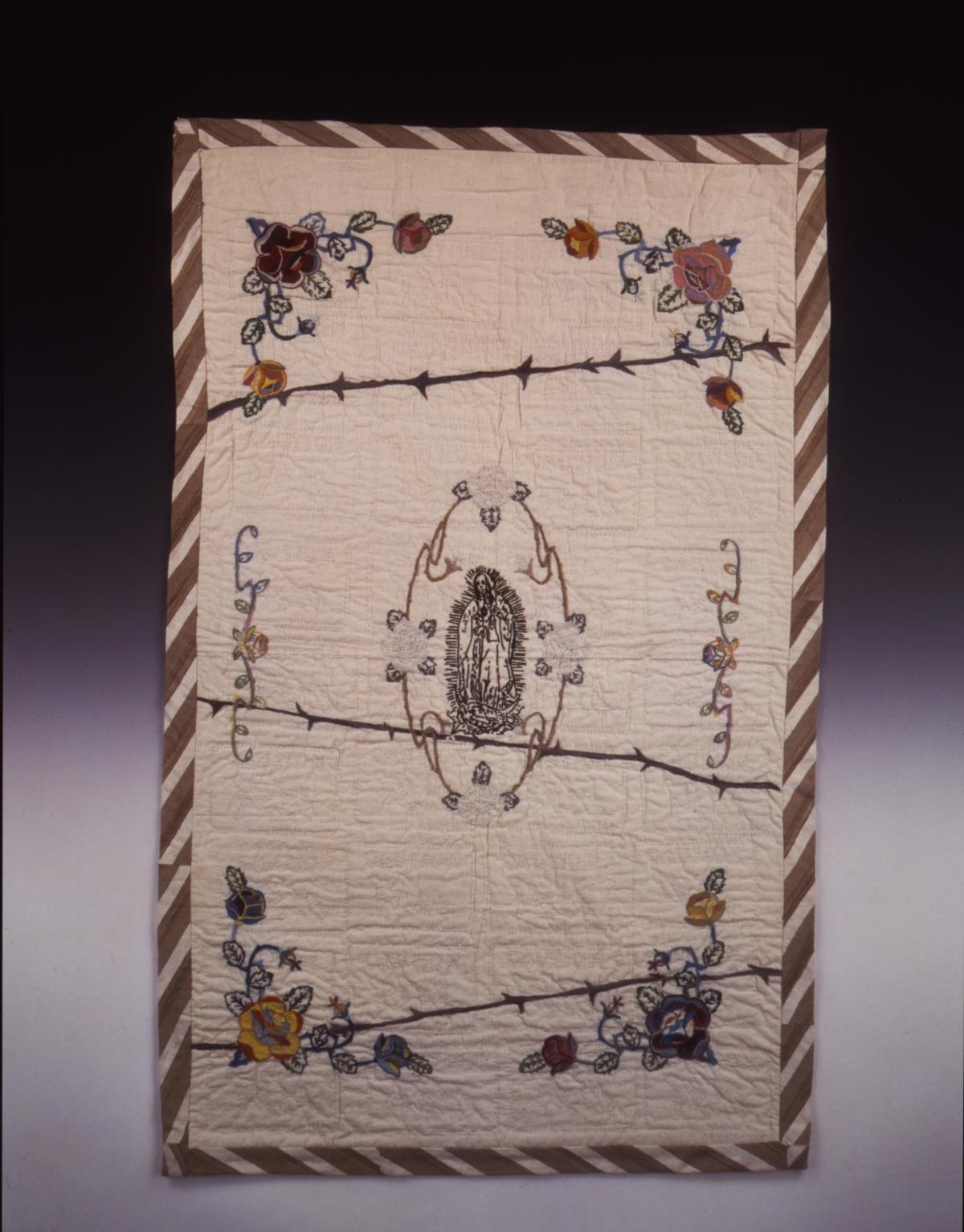

On view as part of the exhibition, Subversive, Skilled, Sublime: Fiber Art by Women at the Renwick Gallery, Underwood’s Virgen de los Caminos (1994) was initially intended as quilt for her baby granddaughter. While she began by embroidering beautiful flowers and, toward the end of the project, realized the quilt was also meant for all little girls who crossed the border. Zoom in to explore this quilt online or visit the galleries for a deeper look.

This brief episode from SAAM’s Backstitch podcast series explores Consuelo Jimenez Underwood’s case for textiles—especially weaving—as art, not folk art or craft. She recounts how the dresses her father wove for her as a child planted a seed that eventually grew to inspire her artistic practice. Underwood explains that her father came from an indigenous background, the Huichol, in western Mexico, in which men made textiles. She explains, “And the baddest—the best wise men, or curanderos, are the ones that have the most intricate, detailed embroideries on their costume, on their dress."

These short- form audio explorations take a deeper look into the lives and creative practices of ten trailblazing artists represented in the exhibition Subversive, Skilled, Sublime. Ranging from eight to thirteen minutes each, it is easy to devour each episode one after another.

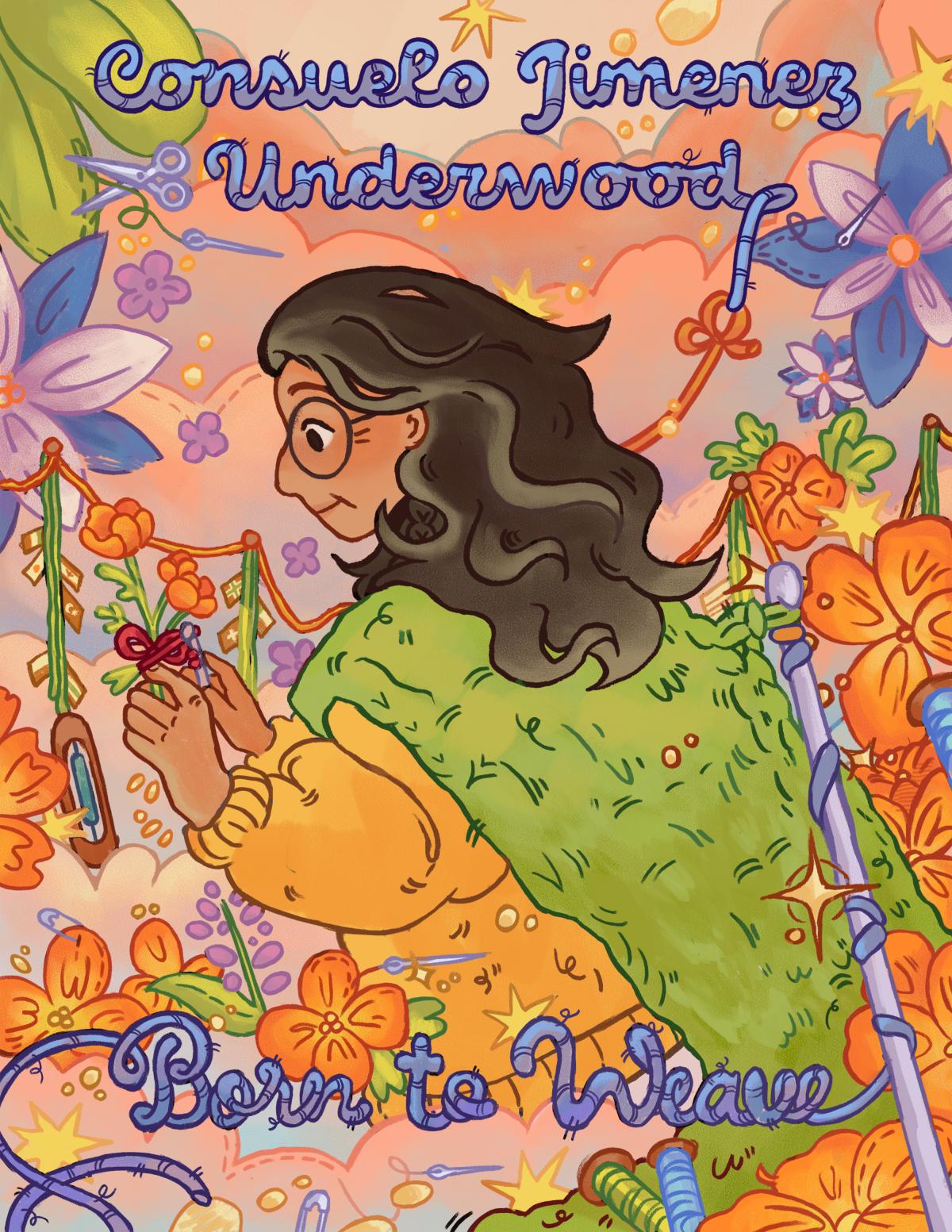

The colorful illustrations of Catherine Vo, a student-illustrator from the Ringling College of Art and Design, conjures magic in her telling of Underwood’s story, “Born to Weave.” In this story the streets are paved not with gold, but with yarn—an interesting word whose multiple meanings include both textiles and storytelling. Twenty-nine more beautifully illustrated comics about the lives of inspiring women artists await as part of the Drawn to Art series.

Finally, don’t miss this engaging “Meet the Artist” video, which offers a visual and conversational exploration of Underwood’s process.