Tom di Maria is director emeritus of Creative Growth, an organization founded in Oakland, California in 1974 that is a leader in the field of arts and disabilities, advancing the inclusion of artists with developmental disabilities in contemporary art. Judith Scott and Dan Miller are two artists associated with Creative Growth whose work has become an essential part of SAAM's collection. This is the first part of a two-part interview. Read part two.

Howard Kaplan: Let’s start with Elias and Florence Katz, the founders of Creative Growth. What was the driving force and founding principles behind their organization?

Tom di Maria: Elias Katz and Florence Ludens-Katz started Creative Growth in 1972 and incorporated it in 1974. Elias was a psychologist who served as chair of the Art and Disability program at the University of California, Berkeley. He was an old-school therapist and hippie shaped by the seventies—that first generation of pop psychology, and empowerment. Elias believed in human growth and potential. His wife, Florence, was an artist who believed that artists should be paid for their work. Because Elias was connected to the psychology community, he understood that people with disabilities were going to be de-institutionalized in California. He and Florence believed that art and creativity offered a pathway for people with developmental and intellectual disabilities to communicate, to become integrated into society, and to realize their individual potential. Their model was completely different from institutionalized life. They started it in their own garage. So, I like to say Creative Growth is just like all the Great Bay area stories including Apple and Hewlett Packard; kind of a crazy idea that started in the garage.

Very early on, the Katzes articulated a whole idea of Creative Growth: it would be a center for artistic exploration led by artists—not doctors. Artists would support and nurture people with disabilities in becoming artists, as opposed to teaching them. Part of the plan would be to have the artwork shown in the Creative Growth gallery and sold to benefit the artists; the gallery would be a portal for the general public to come and meet people with disabilities.

It may seem odd to hear today, but back then, people with disabilities just never had this kind of opportunity: if the kid down the street was born with Down syndrome, they ended up in an institution. And in turn, their disability was hidden from mainstream society. Creative Growth offered a radical idea in terms of advancement, creativity, and community integration. Remember that back in the 1970s, in Berkeley and Oakland, this was the summer of love, hippie culture, free speech, early gay rights, and the Black Panther movement. It was a time of profound social change and Florence and Elias were riding the wave of a new society in breaking down barriers around who people are.

Is the local community supportive of Creative Growth?

The Oakland/Bay Area community is very supportive of our artists, and of Creative Growth as a community center and cultural hub around disability and creativity; it’s also very supportive philanthropically. In terms of the art itself, we’ve found it is best understood simply as contemporary art. Support for Creative Growth comes from beyond the Bay Area as well; we have a thriving exhibition and sales program and regularly work with museums and galleries in New York, Miami, Paris, and elsewhere.

In general, do people who come to Creative Growth have an art practice already?

The answer is usually no, and we actually prefer that they don't. The older generation of our artists in particular, haven't had the same opportunities as most of the younger adult artists—who grew up in a different world and had more integration into mainstream society. They may have some art experience, but usually not in a deeply meaningful or lasting way.

Creative Growth approaches the person coming in as a blank slate. We find that creative experiences dwell within each human being. We also find that people with developmental disabilities often face issues around communication, sometimes because they've been asked not to be communicative [or] people haven’t wanted to hear from them. They've been discarded sometimes.

People on the Autism spectrum have a lot of communication issues and may be nonverbal; people who are deaf or blind have different ways that they access language or communicate. Part of Creative Growth’s main focus is: “Let's open the doors to communication and use art to communicate.”

How does Creative Growth expand the meaning of communication through art?

Creativity is a form of communication. What happens if we ask you to communicate instead of telling you to be quiet? You don't have to be creative to stay in this community, a person can take the time it takes. It took two years before Judith Scott made her sculpture; part of the Creative Growth understanding of our people is that we don't assume we can evaluate a person immediately, nor do we expect a certain timeline for change. We understand that people are on different life paths, and it takes the time that it takes. So, we waited for Judith; if she was made to do something within the first year or two, she might not have found her own artistic path, and we might not know her for the body of work she came to produce. So that's part of our practice. It’s worth noting that we’ve never actually had a person working here who hasn't become creative; some are highly productive and achieve widespread recognition, and others you would only know about if you visited the studio—and to us that's all the same. But the creativity happens.

In terms of art therapy in an academic or clinical sense, Creative Growth is not an art therapy center, but something therapeutic often happens during the process of making art, and we certainly see the advancement and personal growth in the artists.

Judith Scott needing two years to acclimate is not unusual?

It's more extreme, but Judith had a more extreme circumstance before she arrived. She spent five or six years with her twin sister at the family home before being suddenly, dramatically, almost violently, separated, and institutionalized for 40 years. She went from being part of a family to being emotionally abandoned. The staff didn't realize she was deaf, so she never had any language acquisition, or anything that would resemble integration into socialization or intellectual stimulation.

When her sister, Joyce, finally had got her out of the institution, she had an epiphany: I have a twin sister and the practice of keeping somebody institutionalized their entire life isn't what we do anymore. Joyce went through the conservatorship process and finally brought her sister to California. The institution essentially put Judith on a plane by herself and sent her to California after forty years of isolation and neglect.

My personal theory about Judith’s first two years at Creative Growth is that if you look at language development in children, they usually start to speak by age two. If language development or some form of communication (like ASL, for example) doesn't happen at all, a human being loses the capacity to develop language.

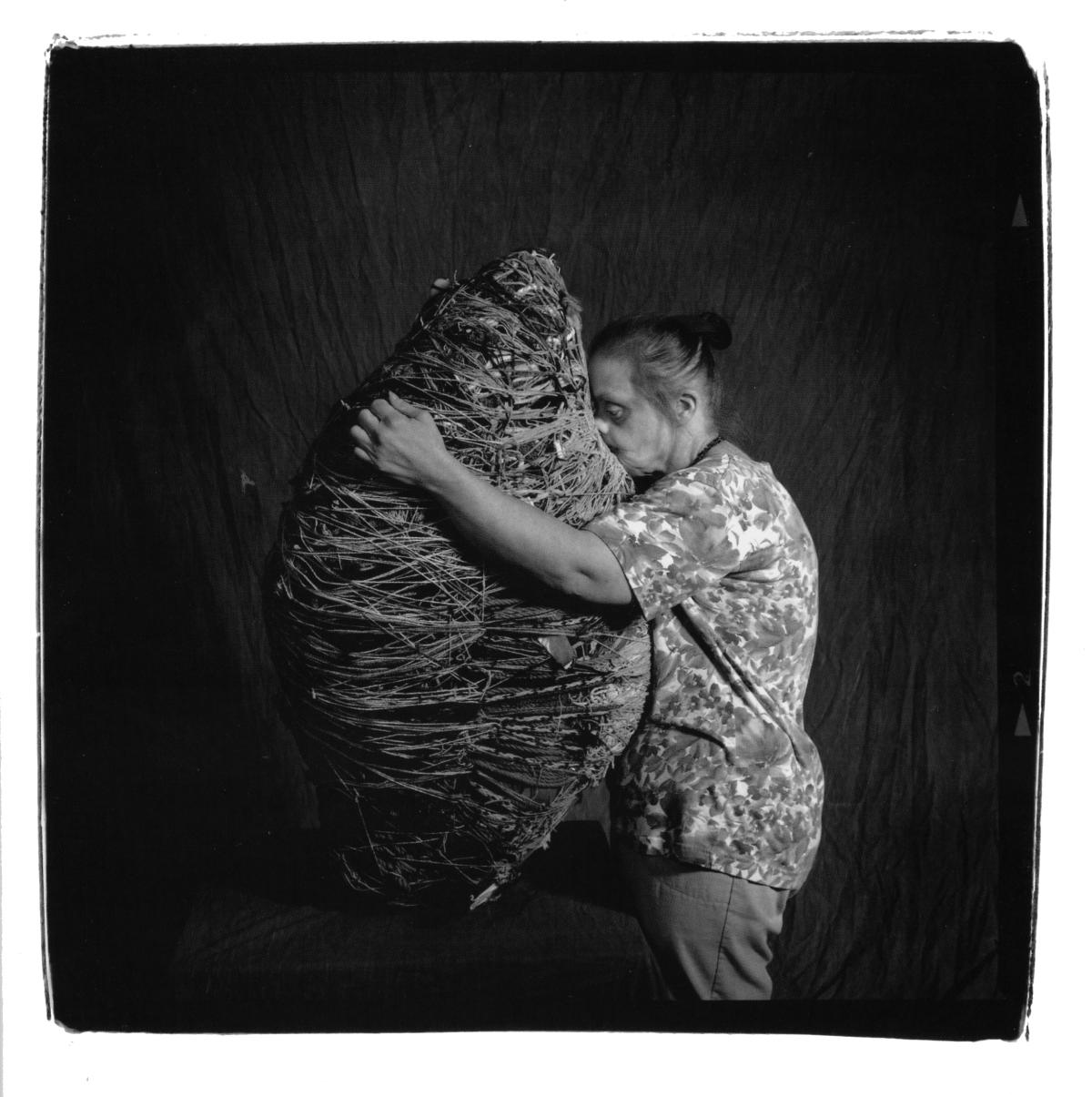

Judith didn't have language. So, she came to Creative Growth, and two years in, she made a sculpture. To me, it felt like, “Oh, this is her second life or rebirth.” She started to speak much in the way that someone new to the world might. She took that time to develop her own language system and found a way to use art as her form of communicating with the world.

Did you work with Judith? What was her process in creating and communicating?

I worked with Judith Scott for about six years. I started here in 1999 and she died in 2005. I worked with Judith almost every day and she had a really interesting practice. We have noticed that many people that grew up in institutions have issues around privacy and protection. She’d hide her materials under her desk at the table where she worked, because there was always a fear that in the morning that anything that was hers would be gone, she had no sense of ownership or of a private place.

Each morning, Judith would walk into Creative Growth and put the sculpture she was working on, on the table and take out her materials. The magazines she collected obsessively were on the chair next to her, as if they were her friends.

Judith gathered all the materials she was going to use (often stolen, or in art world terms, appropriated) and put them in boxes. Judith was a scavenger; she’d walk off the bus carrying different things; one time she found a skateboard on the street, and she dragged it in.

She organized her materials, clustering or combining larger objects such as wood or found objects. She’d them tie them together, and then use a selection of fiber threads and fabric scraps to encase and bind them.

Judith brought her own lunch and ate at her table where she made her work. She held court there, and you didn't mess with that spot. She established a presence, a place, and a practice for herself. Not an easy thing to do when you’ve lived in a locked room for forty years without language or community.

What can you say about Judith’s ability to communicate through her art?

Her practice around using yarn and threads is interesting, because people often say she “wrapped” them and she really didn't, she sort of sewed around them. If you look at the tensions, the textures, and the work, you'll see the threads are almost like a spider web, forming tensions and angles. She was almost creating a web around the found objects. When she was finished with one thread, she cut off the tip and tucked it into the sculpture.

That continued until she was done; sometimes a piece that looked finished and beautiful—and we thought it was done—and then she would wrap it in cardboard and start all over. So some sculptures essentially have sculptures within them. Her late-phase work looks rougher as she had changed her practice stylistically. You might see some pieces of cardboard sticking out or even a set of wheels. These were pieces that I felt weren’t finished at the time but were. You might see some pieces of cardboard sticking out and wheels that I felt like weren't finished at the time, and of course she had just changed her practice stylistically. When she was finished with the piece, she pushed it across the table and clapped her hands together, in a gesture of “I'm done.”

Then she’d point upstairs, because we would take the sculptures upstairs to a storeroom, as if to say, “Get out of here, take it up.” When Judith was finishing some of these late-phase, less “finished” looking pieces I thought, well, she was getting older and maybe she's just exhausted, or they're getting too big for her to move from the floor to the table every day. So, I'd leave them around longer. But she never changed her opinion on them. They were done. And now such pieces are some of the more sought-after pieces. They have a more irregular, contemporary look; the materials have moments of exposure and are almost deconstructed in a way.

Who were leaders in collecting art from Creative Growth artists and how did it change the art world?

The first exhibition of her work was at Creative Growth, when I became the director in 1999, in our Oakland Gallery. When I was hired as director, part of the goal set forth by the board was to advance all of the artists into the contemporary art world. Judith was someone that the board particularly felt was an interesting artist and whose works should be seen. I started a twenty-year program to present her work to different galleries, museum acquisition committees, private collectors. Margaret and John Robson were the first people who came here as collectors. They heard that Scott was making interesting work and they wanted to see it. I organized the viewing, and they selected two or three sculptures that day. Later, when Margaret served a trustee at the American Folk Art Museum in New York, other collectors followed. Then we made a gift to the museum and then a commercial gallery got interested. So, it really started to develop that way. And now it's gone on and Judith has had work included in the Venice Biennale. She’s also had a one woman show with the Brooklyn Museum of Art, among other venues.

Doug Robson used to come by with his mother, Margaret. I've known him for a while, and he became a more active collector after Margaret died—both of Dan Miller and Judith Scott. Until recently, Doug was a Creative Growth board member. As a collector, when he was working on the donation of the Robson family collection to SAAM, he was thoughtful about rounding out representation. He added a couple of significant pieces, including Miller’s Untitled (239_2016), which was installed in his New York apartment until he donated it to SAAM. Doug felt like it was a masterpiece that could offer a deeper understanding and presentation of Dan’s work. It was featured in the exhibition, We Are Made of Stories: Self-Taught Artists in the Robson Family Collection and will be on view again in SAAM’s third floor galleries for modern and contemporary art. Doug and curators at SAAM agreed that representing Miller in this setting would be critically important.

Margaret was among the first collectors of self-taught work who really saw Scott’s work as being an exciting expression from a contemporary artist who was finding her way after a past filled with trauma and isolation. Robson was taken by the works unique forms and surfaces, the hidden objects buried within, the obsessive making and the way her work served as a unique form of communication between her and the viewer.

Do other artists at Creative Growth see Scott as a mentor?

Here is an interesting story about how Judith Scott has become a role model for other artists here. We have an artist here now, Eli Cooper, who has Down syndrome. His mother was a Creative Growth board member and he grew up here in the studio, coming to meetings, hanging out, and knowing Judith Scott. He became a Creative Growth artist when he turned twenty-one, and one of the first gallery exhibitions we did upon reopening after the pandemic asked artists to do a site-specific piece about what Covid was like in terms of being homebound.

Eli took over the gallery and installed it like his bedroom, including a couch, his photo-collages hung on his walls, the junk food he ate, the videos he watched. We have a green screen animation; he recreated the videos he was watching. It was the best title ever for a gallery show: “Suck my 2020,” and it was an amazing site-specific installation that included his video performance work along with his visual art and gallery design.

Then he said, “I want to do one more thing. I need to include Judith Scott’s work in my show because she was such a role model and inspiration for me.” We showed him images of her art he could use; he picked two pieces and installed them on the wall. He wrote about how she was an inspiration for him as an artist with Down syndrome.

For me, that's really important; it's the first time that I'm aware of that an artist with a disability responded to an artist with a disability as a hero and a mentor practitioner—without ableist intervention of someone like me or the studio, or the structures that usually mediate between people with disabilities.