Ah, early September. While many of us are dreaming of one last beach getaway, teachers and students around the country have already headed back to the classroom. You might be surprised, however, to hear some of the ways artworks in SAAM’s collection will be showing up with them!

This July, SAAM welcomed 59 English/language arts and history teachers from 25 states and China to participate in one of our week-long Summer Institutes: Teaching the Humanities through Art. Participants spent five days with the museum as their classroom, learning with museum professionals and one another to explore how American art can be a conduit to meaningful learning across the curriculum. By the end of the week, each teacher had designed a lesson concept using at least one artwork from SAAM’s collection. Based on some of these lesson concepts, here are 5 ways teachers will be using American Art in their classrooms this year:

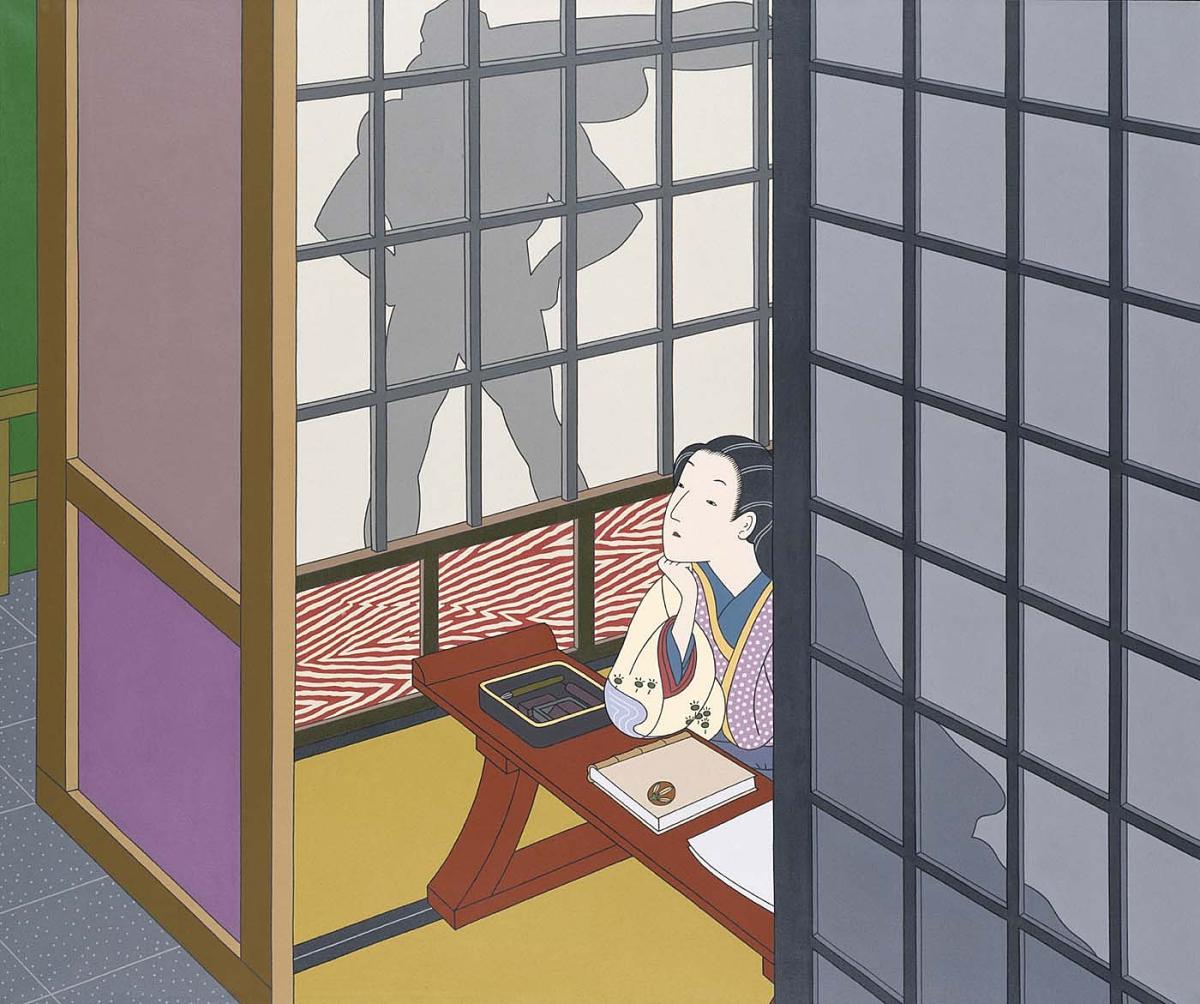

Building Critical Media Literacy

Lexi Hartley, an English and history teacher for grades 6-12 in Ithaca, New York, teaches about Japanese American internment during World War II in her “Childhood and Conflict” course, so she quickly connected with Roger Shimomura’s Diary, December 12, 1941. The 1980 painting was inspired by a diary entry written by Shimomura’s grandmother, a first-generation Japanese immigrant who was interned in Minidoka during the war along with a young Roger and his family. Hartley will use the painting as a way to discuss generational differences in experiences of internment, but also as a connection to the idea of government propaganda. The shadowy superhero figure in the painting alludes to the way Superman was used as a symbol of American power during World War II, and used to justify anti-Japanese sentiment and legislation. Having her students analyze examples of these comics from the National Museum of American History, Hartley believes they will become more critical consumers of visual media in their own lives.

See more on the Smithsonian Learning Lab.

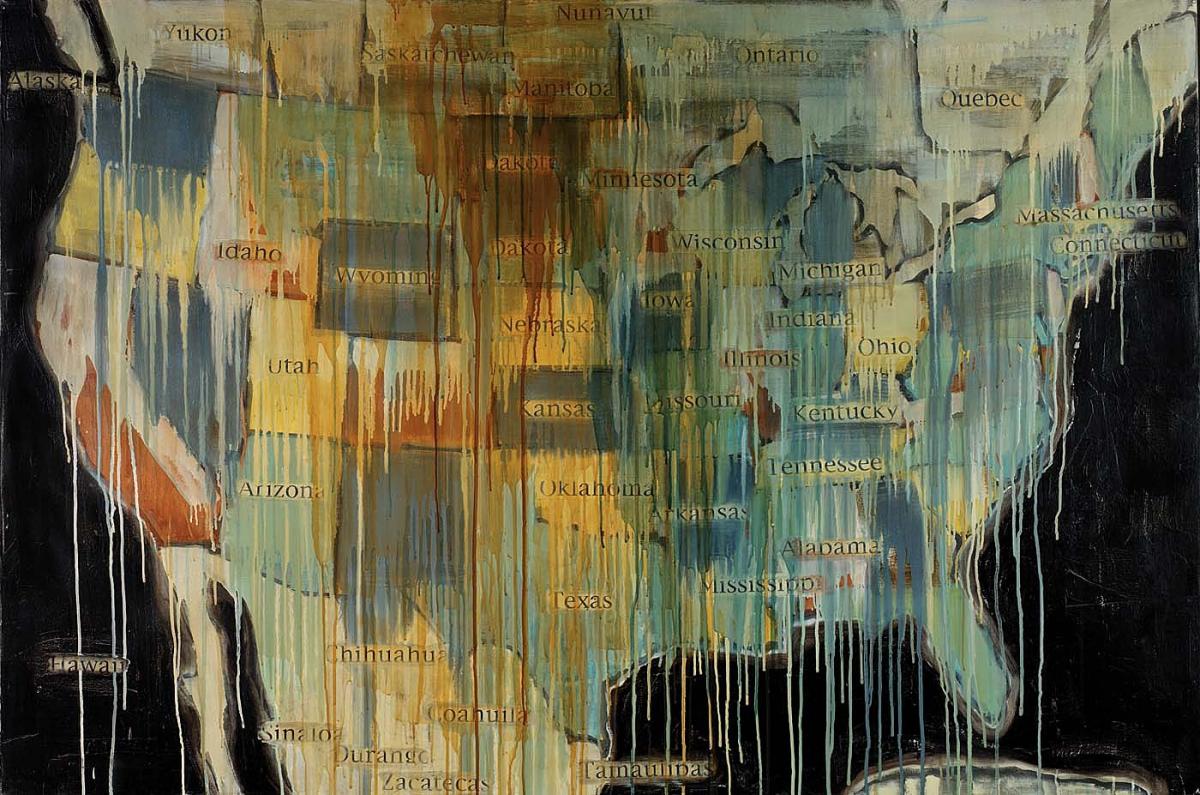

Centering Marginalized Narratives in History

Kameko Jacobs, an 11thgrade U.S. History teacher in Round Rock, Texas, wants her class to challenge students’ pre-existing ideas about the founding and settlement of the United States. She plans to have her students observe and interpret two artworks in SAAM’s collection with very different perspectives on this: Emmanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s Westward, the Course of Empire Takes Its Way (mural study, U.S. Capitol) (1861), and Jaune Quick-To-See Smith’s State Names (2000). Smith’s painting, depicting a map of North America that includes only the names of states and provinces that originate from Native languages, will set the stage for a larger consideration of the absence and/or whitewashing of Native American experiences from the dominant historical narrative.

See more about marginalized narratives in history.

Examining our Relationship to Technology

Many of today’s high school students don’t remember a world before smart phones, let alone TV screens. Mathieu Debic, a high school English and Composition teacher in Dallas, Texas, plans to use the artwork of “father of video art” Nam June Paik to prompt student reflection on the role technology plays in their lives, and how it’s changed even within their lifetimes. Debic will use a video filmed in SAAM’s galleries, along with a still image, to allow students to experience the immersive sights and sounds of Paik’s Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii. After exploring Paik’s work further and reading two recent magazine articles on humans’ relationship to digital technology, students will write essays arguing for or against the idea that digital technology tends to improve human life.

See more about our relationship to technology.

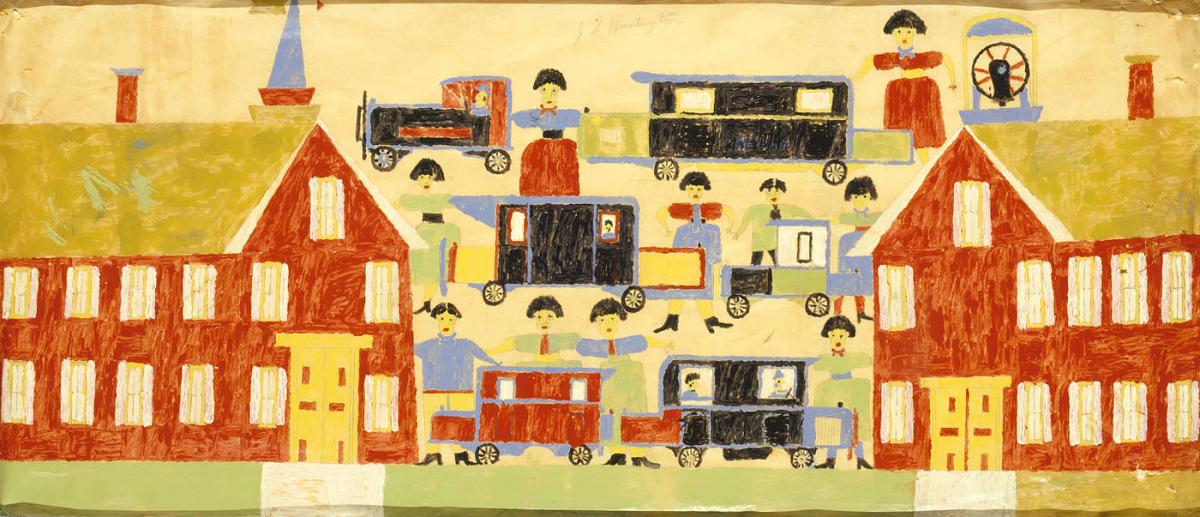

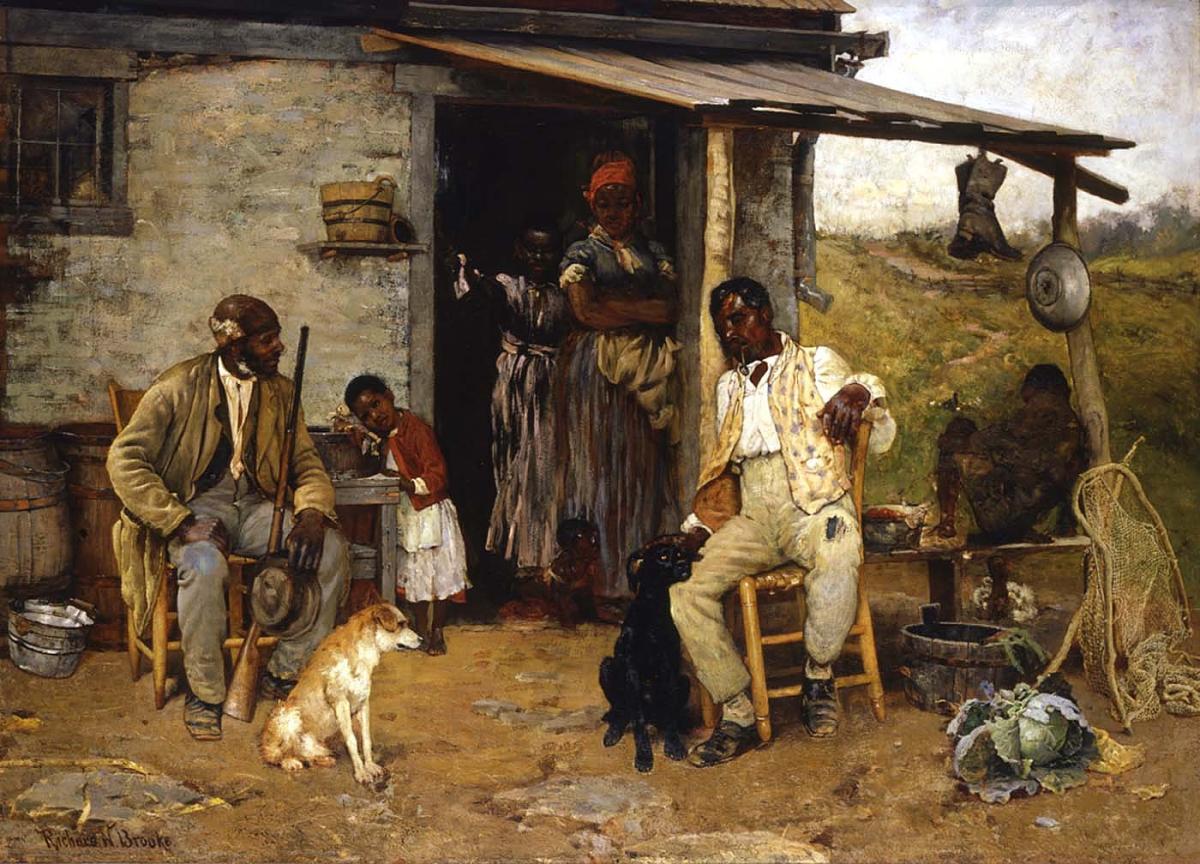

Connecting with Local History

When 6thgrade English teacher Selena Dickey discovered that SAAM’s 1881 painting A Dog Swap was painted by a native of her own Warrenton, Virginia – Richard Norris Brooke – she knew she had to incorporate it into her local history curriculum. Through research, she discovered that we actually know the names of the African American Warrenton residents depicted in the painting, as well as the probable location of this house – not far from her own home or the middle school where she teaches. She plans to use Brooke’s painting as an introduction for students into a deeper study of their community’s history.

See more about connecting to local history.

Engaging with Contemporary Social Justice Movements

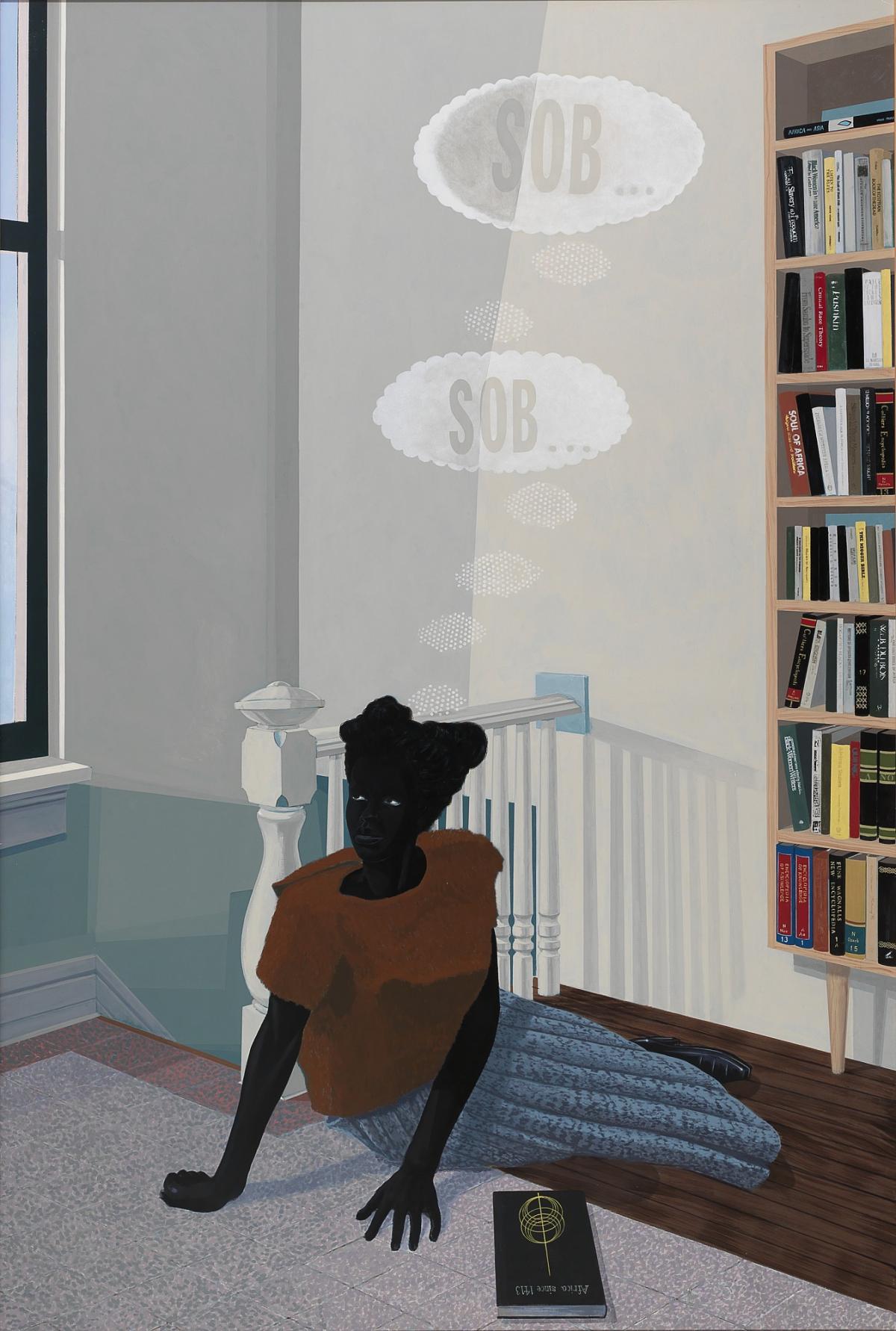

It’s important to Katie Belanger, a high school English teacher in St. Louis Park, Minnesota, that her students look both inward, considering their own identities and experiences, and outward, to real-world issues and perspectives beyond their own, when reading literature in her class. This year, her 9thgraders will be examining what it means to be black in America today, while reading one of several contemporary books centered on African American protagonists. She plans to use Kerry James Marshall’s SOB, SOB at multiple points during the unit as a prompt for group discussion and critical thinking, and a springboard for students to consider their own views on social justice movements like #blacklivesmatter.

See more about contemporary social justice movements.

Intrigued by these teaching ideas? If you’re an educator interested in attending a future Summer Institute at SAAM, please check our webpage later this fall for 2019 dates and application details.