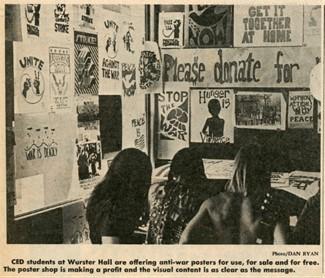

In 1970, Ronald Reagan was outraged. As governor of California, he accused Berkeley students of stealing materials from the university to make anti-war posters and was going to prove it. However, instead of capturing the presumed thieves, he ended up funding a detailed report that tells the story of radical, artistic upcycling.

Spearheaded by the accounting firm Haskins & Sells, the report details Berkeley students’ use of continuous form paper, also known as tractor feed paper or IBM paper, to create protest screenprints. This type of printing paper is defined by its perforated sides and connected printing sheets. Duplex or double-sided computer printing would not arrive until the 1980s. So in 1970, discarded printouts, set out for recycling, offered protest artists a free supply of paper with a blank side they could use. While the report stated that the recycled material had “no value to the University,” to the students it would be an invaluable resource to support their political causes.

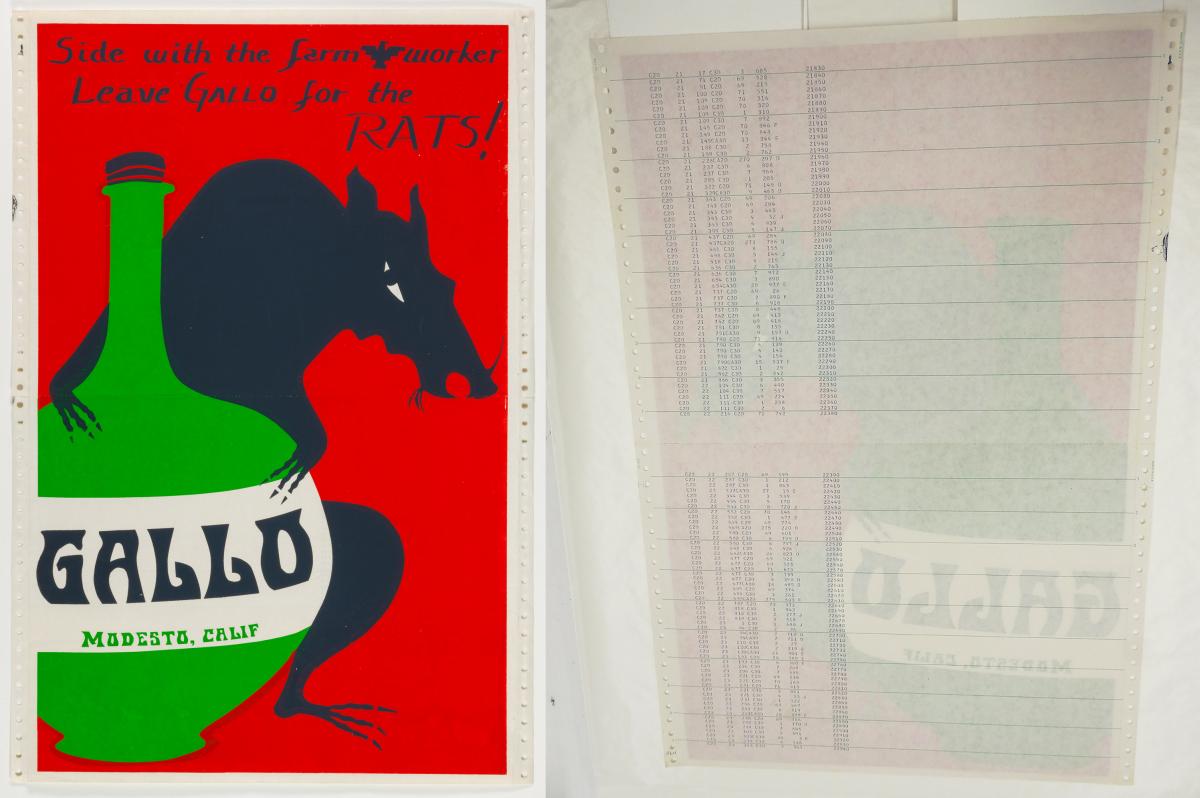

Untitled (Side with the Farmworker), dated ca. 1973, is an example of a tractor paper print, which SAAM received as part of a generous donation from the estate of Margaret Terrazos Santos. While the origins of the print are still being studied, scholar and archivist Lincoln Cushing believes the print may have been produced at Méchicano Art Center in Los Angeles. Notably, the print’s underside has long strings of numerical data, suggesting this is recycled computer paper. The three-color screenprint features a silhouetted rat embracing a Gallo wine bottle; at the top, the emblazoned phrase, “Side with the farmworker Leave Gallo for the RATS!,” calls for action. The artist also incorporated in the work the winged logo of the United Farm Workers (UFW) to underscore their support of the labor union.

Since the 1960s, the UFW has advocated for farmworkers’ rights and labor reform under such notable leaders as César Chávez and Dolores Huerta. In 1973 the UFW and E.& J. Gallo Winery were at odds. Gallo’s labor contract with the UFW had ended that year, and instead of renewing, Gallo went with the Teamsters Union. As a result, the UFW called for a national boycott of all Gallo products, spurring a decades-long feud and the subsequent creation of boycott-related imagery in support of the UFW. The artist of Untitled (Side with the Farmworker) aligns themself with UFW’s strike and appropriates protest rat imagery to further vilify Gallo. The image bears a striking resemblance to the French print Vermine Fasciste, Action Civique (Fascist Vermin, Civil Action), a poster created in 1968 during student protests at the University of Paris. Mexico, Cuba, and France would also be a common source of inspiration for protest art. Rat imagery is common today, as seen in Scabby, the giant inflatable rat, commissioned in 1990 by a union in Chicago and used for labor strikes.

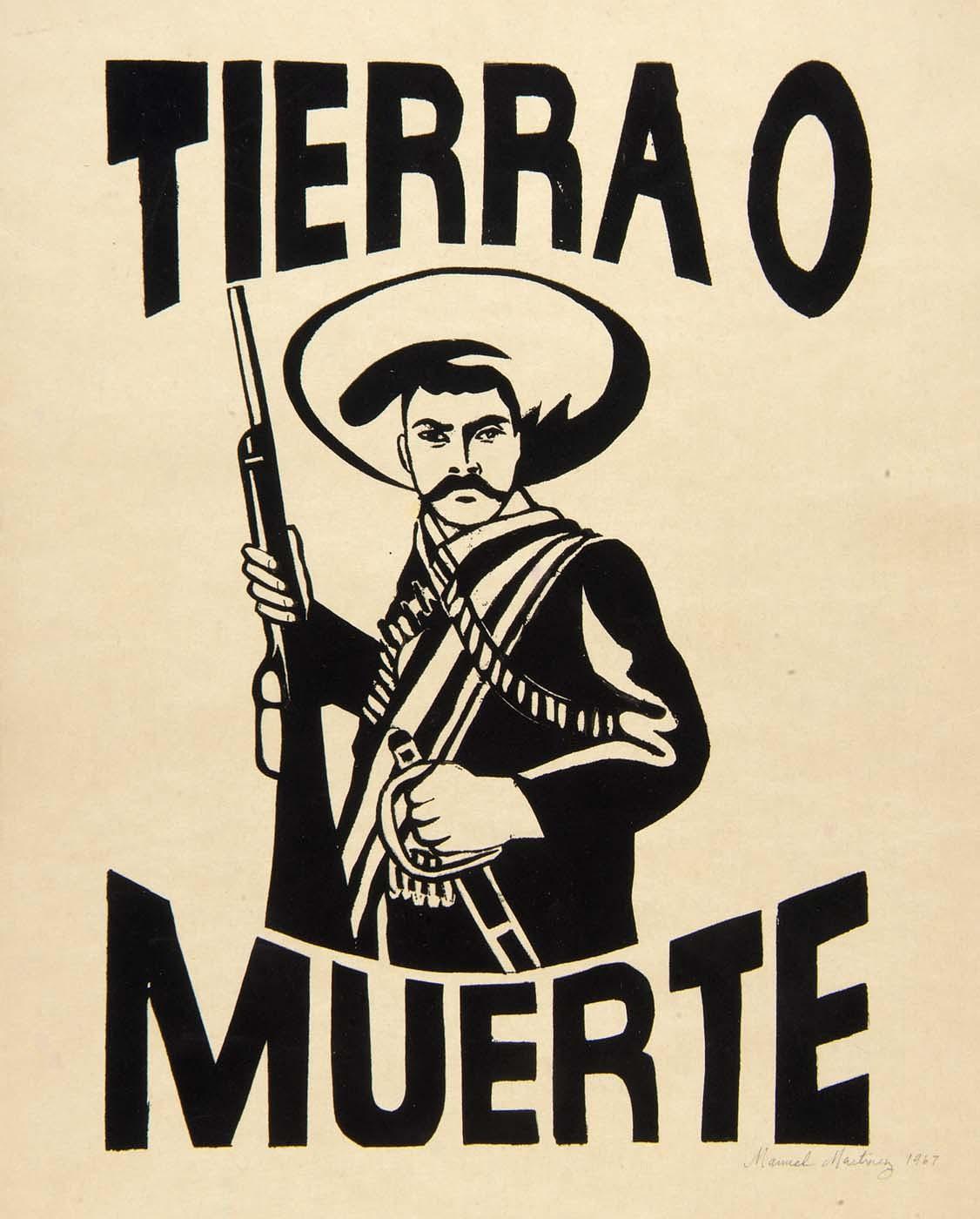

For protest artists, the substrate, or the material that receives the image, is often of little importance; it is the image’s political message that is vital, as seen with Emanuel Martinez’s 1967 screenprint Tierra o Muerte. But the paper substrate, and the ways in which the print circulated in the world, can add another layer of meaning. Martinez printed this work to back the Alianza Federal, an activist organization in New Mexico that fought to reclaim communal land rights guaranteed under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848). The organization had meager funds, so the artist used donated manila folders as the substrate for his now iconic image. As a student at San Francisco State University in the 1960s, veteran printmaker Rupert García helped organize a print workshop whose posters were also sold to raise funds for student strikers’ bails. Under such time constraints, poster artists would often forgo formal labeling practices associated with fine art prints such as signatures, chop marks, edition numbers, and titles.

Political works have an urgency to them and are meant to circulate quickly to spread a message, support a cause. By rethinking the utility of discarded materials, protest artists showcased their ingenuity and moved with the times. Where we might see nothing of value, political artists see vital art supplies. With upcycling, they used every resource at their disposal to show solidarity and advocate for change.