Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, is currently on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum's Renwick Gallery, the third stop on a national tour for this groundbreaking, eye-opening exhibition. It is the first major thematic show to explore the artistic achievements of Native women. At the core of this exhibition is a firm belief in the power of the collaborative process. In 2015, exhibition curators Jill Ahlberg Yohe and Teri Greeves (Kiowa Nation) formed the Native Exhibition Advisory Board—a panel of 21 Native artists and Native and non-Native scholars from across North America—to provide insights from a wide range of nations at every step in the curatorial process. Juline Chevalier, head of interpretation and participatory experiences at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, wrote this story, which was originally published June 13, 2019 on the blog of the Minneapolis Institute of Art where the exhibition originated.

Language matters.

More than three years ago, when the Minneapolis Institute off Art (Mia) was planning the exhibition Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, we wrote grants that said we would translate the labels for the artworks in the exhibition into a Native language. The presentation at SAAM's Renwick Gallery includes the art of more than 80 Native women, from the past 1,000 years—it’s the first major exhibition of its kind. Featuring a Native language was in keeping with the nature of the show, and at the time I assumed it would be Dakhota, the main Native language of central Minnesota.

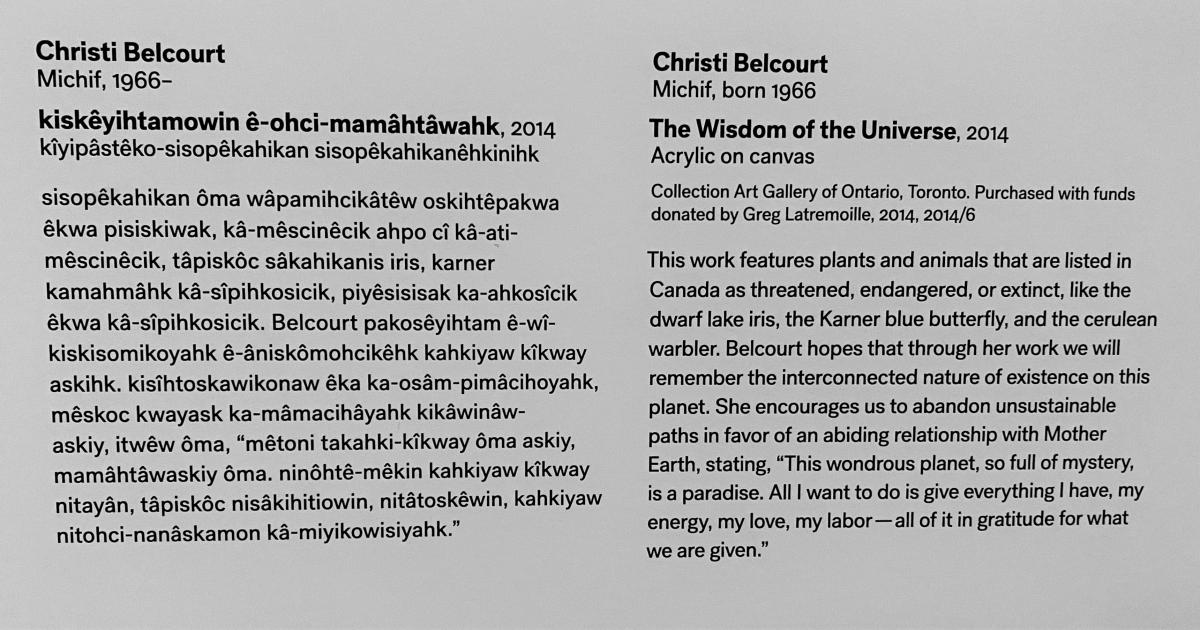

But as the exhibition drew closer, we realized this wasn’t an equitable plan. Why just one Native language, when several are spoken in Minnesota? Also, the exhibition is traveling to other parts of the United States that are home to different Native people with different languages. Native culture is not a monolith. We concluded that the most fair thing to do would be to translate each label into the language of the artwork’s maker.

And then we all paused to consider whether we could really take this on. More than 30 languages, more than 100 labels. With less than a year until the exhibition was to open, we decided to go for it.

A core group came together: Jill Ahlberg Yohe, the co-curator of the exhibition and Associate Curator of Native American Art; Dakota Hoska, Curatorial Research Assistant; Tobie Miller, Curatorial Department Assistant and Artist Liaison for the Department of Arts of Africa and the Americas; Juline Chevalier, Head of Interpretation and Participatory Experiences; and Esther Callahan, Curatorial Fellow.

We wrote more than 100 labels in a month, trying to keep them to 100 words or less. Seems like it might be easier to write less than more, but as Blaise Pascal observed, “I would have written you a short letter, but I didn’t have the time.”

With languages like Spanish, Chinese, or Portuguese, you can readily find professional translation services on-line. It’s generally pretty easy: you send them text, they send you a translation. If you want to play it safe, you ask a native-speaker to review the translation.

But with Native American and First Nation languages, it’s not so straightforward. We started with the incredible network of Native women advisors who helped create the exhibition, asking for introductions to interpreters. Often, a friend of a friend led us to someone who could do the job.

Then, we needed to make sure we could actually print the languages. Many orthographies (the written form of language) of Native languages use accent marks and characters that are not part of English fonts. Esther Callahan, along with Aaron Barger in MIA’s Media and Technology department, discovered that a Hungarian font had almost all the accents needed. In some cases we relied on fonts created for free use on the internet.

Some texts were not translated, based on the wishes of the community. Some Native communities don’t share their language with outsiders. Others will share if a long-term relationship and trust has been built with an institution, but we didn’t necessarily have that, and hadn’t started the process early enough to create an authentic partnership. MIA respects these decisions and honors the wishes of sovereign Native nations.

A few objects in the exhibition are ancient. We don’t know for sure what language the makers of these objects spoke. In some cases there are several existing Native-language communities that claim a single ancient people as ancestors. How would we choose just one? And in some cases, one existing language community might not recognize others who claim the same ancestors.

It’s been an incredible process with lots of ups and downs. We’re still working on finding interpreters for several languages. Rarely do we update labels once an exhibition has opened, but we likely will in this case.

Language matters. Representation matters. It’s worth it.

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists is on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum's Renwick Gallery through May 17, 2020.

Read about the all-female Exhibition Advisory Board, which included Native artists, curators, and Native art historians, who collaborated on the exhibition in an earlier blog post, How Native Women Artists Guided the Creation of Hearts of Our People.

Check out NPR's All Things Considered for a feature on Hearts of Our People.

This story was originally published on the blog of the Minneapolis Institute of Art. It has been edited for clarity.