In honor of Pride month, we've launched an occasional series where SAAM staff take a close look at meaningful works of art in our collection.

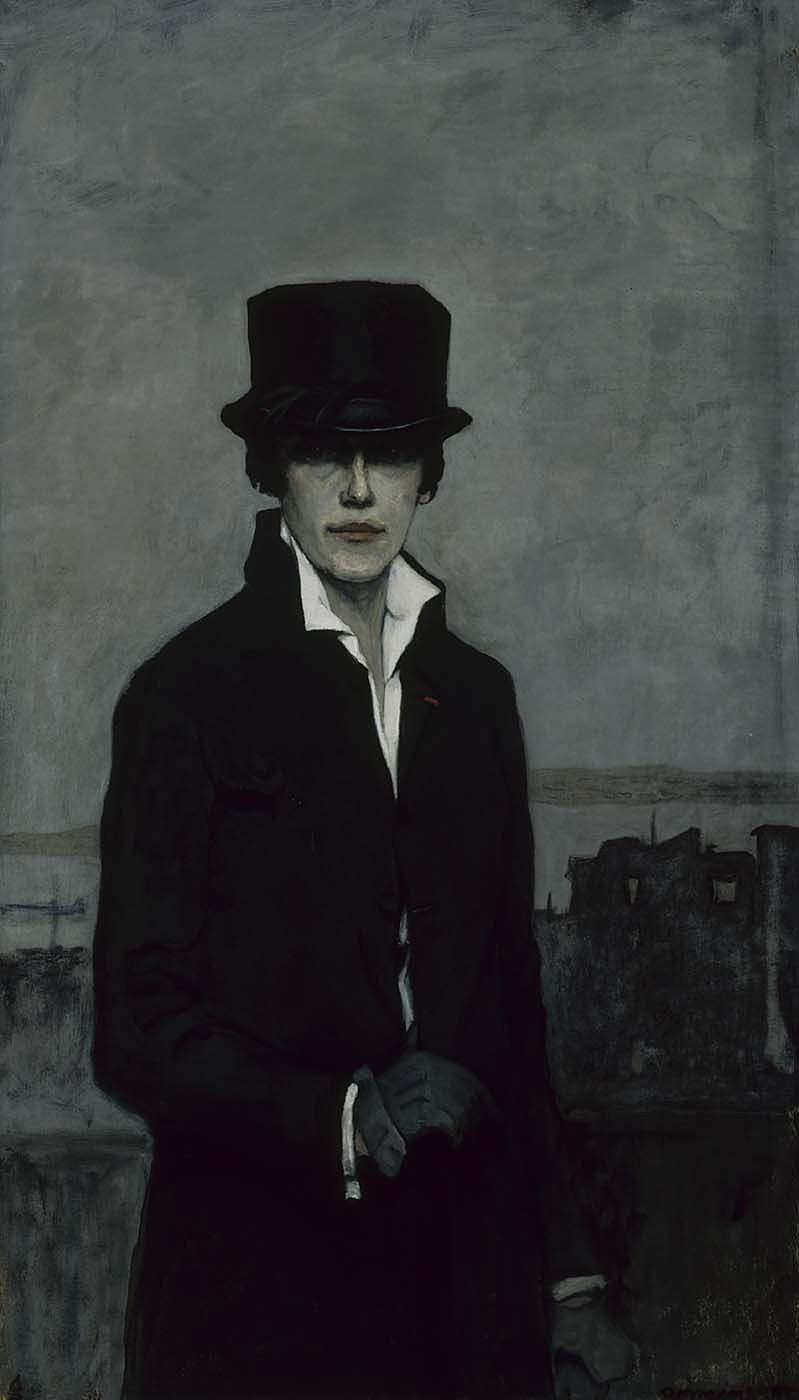

The first time I saw Romaine Brooks’ Self-Portrait in person—at SAAM's 2016 exhibition of the artist's work—I was captivated. I clearly remember stepping off the elevator and there was Brooks down the hall, commanding the space and declaring herself. As I approached the portrait, I could feel becoming more enwrapped by her—trapped in her gaze. I couldn’t help but stand there looking back at her in silence. Initially, I could not see the light reflected in her eyes, but I could sense it. It was weeks after the first encounter that I realized the shadow the brim of her hat cast did not hide her eyes, it only partially obscured them. There was light there; Brooks was staring back at me with a calm strength. Her back to the destruction of the past, looking forward to the future.

I was struck by her clothing—her greatcoat and top hat the deepest of blacks. The gray of her gloves is echoed in the sky and in the forms in the background. Her white collared shirt boldly declaring itself from beneath the heavy greatcoat. Is she referencing the greatcoats soldiers wore? There is a dash of red—a bold vermillion—on her lapel suggesting the ribbon of the Legion of Honor she was awarded. Another a hint of red, though far more muted, in her lips draws your eye to her face. Behind her the shadowy, inchoate forms suggest burned out buildings. Does she stand before the ruins of the Great War? Or could the ruins be a metaphor for her leaving the past behind her? Her past struggles to define herself and find a community of her own. The pain, horror, and destruction that occurs when you’re told who you are is innately wrong.

For queer people we are told who we are by others. We are defined in ways that, especially during Brooks’ lifetime, are intended to diminish, demonize, and dismiss us. We have been pushed as far from the center as we can be—the whispers along the periphery. For LGBTQ+ people it is a radical, transgressive act to publicly declare who we are. To take in what we are told we are, to define our own desires and ideas, and then turn that back outward. The dark colors and shadows in Self-Portrait could suggest that we will never know Brooks’ true self. Or they could be a reminder that Brooks is the arbiter of her own identity, and truly knowing her is a privilege only reserved to those who take the time to sit with her and listen.

I don’t know if Brooks intended to say all of this when she painted Self-Portrait in 1923, but this is what I felt almost 100 years later as a queer man mesmerized by her work. I felt kinship. I felt community. I felt the presence of a woman who declared herself before all. I felt her strength, her journey, her vulnerability, and her honesty. The shadow across her face is not a defense, but an affirmation that you, the outsider, are not owed the privilege of knowing Brooks fully. You do not define her; she defines herself. There will always be parts of our identities that are only revealed to the people who care. We must spend time getting to know Brooks on her own terms.

Artists use their work to speak, and I feel honored to sit with Brooks’ Self-Portrait every time I can. It is an opportunity to know her more deeply. Certainly, we must acknowledge that Romaine Brooks could declare herself the way she did because of her wealth and privilege; many queer people of her era could not afford to do so. But that does not diminish what she’s doing, it merely provides a more nuanced understanding of the queer experience. Looking at Self-Portrait, I feel a profound connection to the past; not just an idea of the past, but an actual person who lived, loved, and spoke her truth. I am reminded that my present is what it is because of those who came before, and I feel a deep connection to the future.