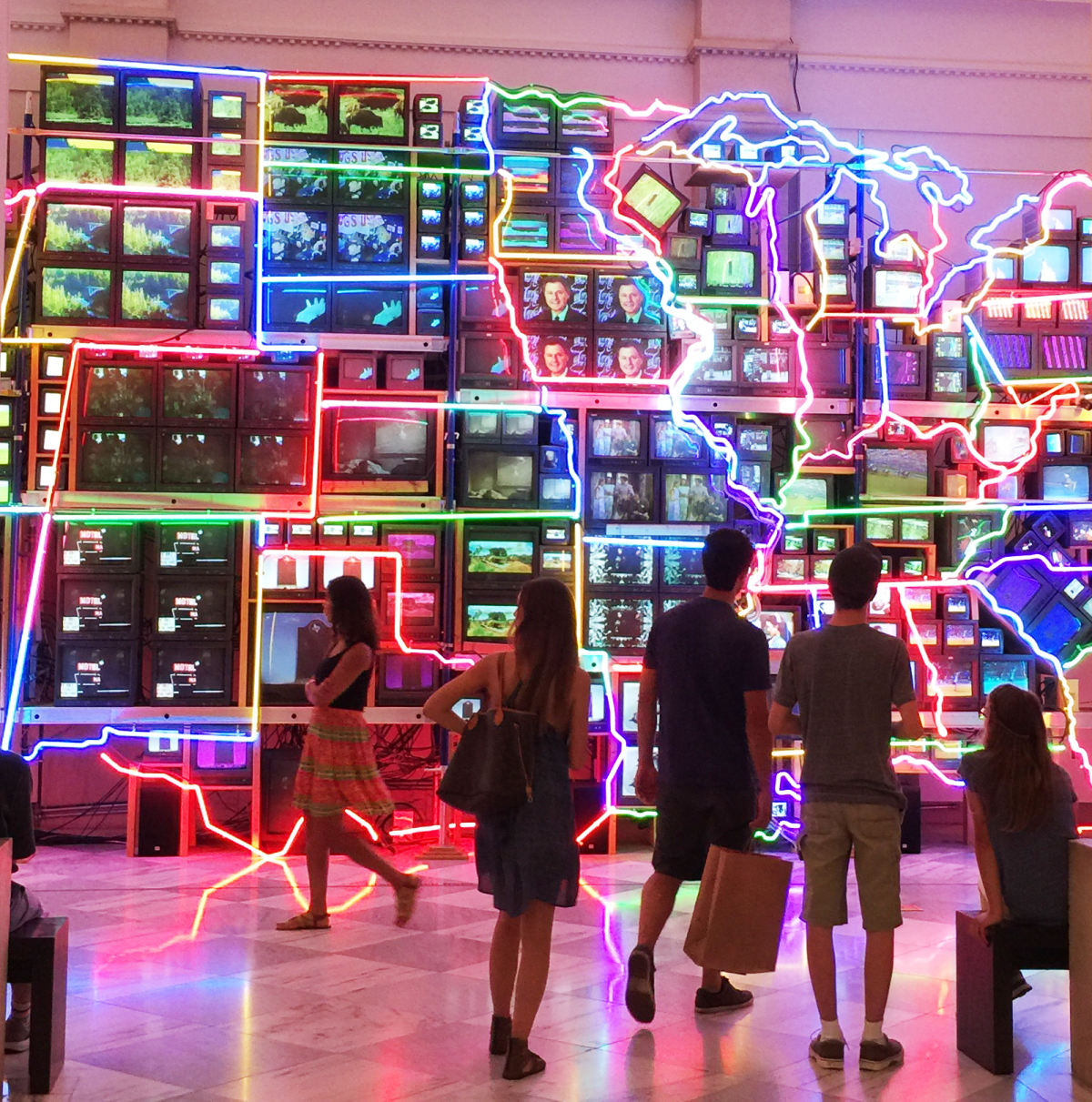

“Only connect,” is the phrase that comes to mind when I take a close look at Nam June Paik’s Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii. Those words from E.M. Forster seem to ring even more true during the pandemic, as we’ve come to be connected to our family, friends, and colleagues often through our screens. “We are all in this together” is also something I heard and appreciated as we navigated through the unknown. Even the word together took on new meaning.

As Saisha Grayson, curator of time-based media at SAAM tells it, “Paik is one of the most important figures of the twentieth century. And, in many ways, he represents looking ahead to the twenty-first century, both in his biography and in the materials he uses and the themes he touches on....And so, in a period of time where many artists were painting with brushes and on canvas, he encouraged artists to not be afraid of working with televisions, working with video, working with electronics, and seeing them as legitimate spaces for art making.”

Paik, born in South Korea, came to the United States in 1964. In a way, Electronic Superhighway is his homage to his new country. The work speaks not just to burgeoning American cross-continental highways, but a digital road that would expand as technology became more prevalent in our lives. Each of the fifty video vignettes is a snippet of what Paik understood that state to represent, often through popular culture and/or his connection to the state. In the window into Kansas, we see a film clip from the Wizard of Oz, while Washington shows the modern dancer Merce Cunningham in action, who was born in Centralia and collaborated with Paik on other projects.

Audio is central to the piece as well. When a movie musical plays, you may hear a show tune when it gets loud. An important part of the sound representing Alabama is the Montgomery Bus boycott documentary that has sections with Martin Luther King and Malcolm X speaking. Here, Grayson makes an important connection: "I think that really interestingly intersects with the idea of the open road and this idea of the highway as a space that, very often in this piece, is seen as a glittering invitation to the fifties idealized open road and American post-war prosperity. But the inclusion of that section and the fact that the artist wanted that audio to be legible, no matter where you were standing, really means that the visuals are always inflected by this questioning of who can get on the road safely? Who will get equal treatment on that road? Who will survive that encounter? And those are questions that stay really resonant and important to this day, unfortunately."

Electronic Superhighway is made of 336 televisions, and when it was first installed fifty DVD players (we now use media players), 3,750 feet of cable, and 575 feet of multicolored neon tubing. In addition to each state, the District of Columbia is also represented. But here, a camera replaces the video monitor. When you stand in front of the artwork, you become a part of Paik’s electronic masterpiece. Only connect, indeed.

Learn more about this iconic artwork in the American Art Moments video below, where Saisha Grayson discusses its creation, its relevance today, and the lasting impact of Nam June Paik’s vision.