When New York businessman John Gellatly’s art collection was installed at the Smithsonian Institution for the first time in 1933, commentators strained to describe the 1,600 works of fine and decorative art that it contained. One widely circulating Associated Press story focused on one small, strange object—so small and strange that it has until recently been almost forgotten among the holdings of what is now the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Newspapers at the time described this precious diorama as “an icon-like concoction of cigar boxes, broken glass and beads, braids, and knick-knacks from the 5 and 10 cent store.” Constructed by Gellatly’s butler-turned-curator, Ralph Seymour, the assemblage was an attempt to salvage the fragments of “an exquisite old bottle of fifteenth-century iridescent glass” that “was broken beyond repair.”

Originally installed in a case with Venetian glass pillars, the diorama also includes tiny reproductions of a carved desk (the full-size version is currently used by SAAM’s Director), American painter Abbott Handerson Thayer’s Stevenson Memorial, and “the case of rare glasses that Gellatly often sat fingering late into the night.” It was, readers were told, “an exact miniature of Gellatly’s favorite corner, and each object in it may still be recognized by a keen observer as a copy of something in the collection.”

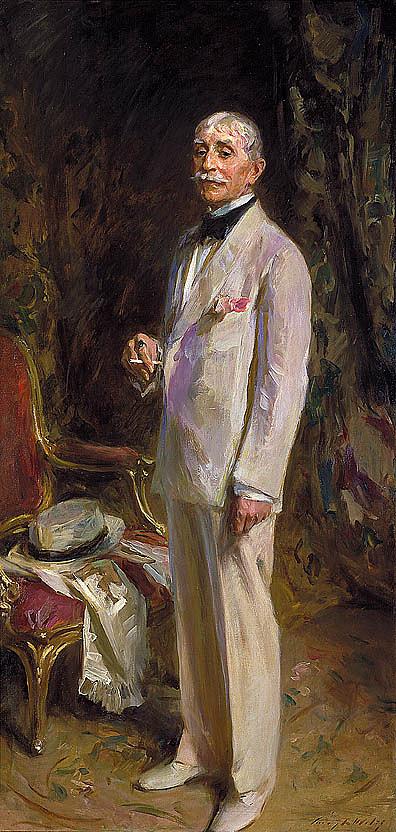

Gellatly's professional life prepared him well for his personal passion for collecting art. As a salesman for pharmaceutical company W.H. Schieffelin & Co., he was expected to design exhibitions of the company's material medica displays along with flowers and other decorations. His leadership position at the New York Architectural League led him to organize winter loan exhibitions in decorative painting and design, incorporating Tiffany glass and pictures by Will Hicok Low and Edwin Howland Blashfield. These experiences undoubtedly helped Gellatly with his own collection of art and artifacts. Bolstered by a shared preference for decorative painters with his wife Edith Rogers, his collection was substantially underwritten by her inherited resources.

Critic Annie Nathan Meyer cited Gellatly in 1905 as a praiseworthy example of a collector who was truly “living with” his artworks rather than amassing them for show or sale, but who and what did a guest to the townhouse at 24 West 57th Street see?

Gellatly’s picture collection was particularly rich in works by American Aesthetic movement painters such as Thomas Wilmer Dewing and Frederick Stuart Church, as well as Albert Pinkham Ryder and Childe Hassam. But no artist found greater representation here than the New York– and New Hampshire–based aesthetic painter Abbott Handerson Thayer, from whom Gellatly would eventually acquire at least twenty-three pictures. His Stevenson Memorial served as the centerpiece of Gellatly’s favorite collecting corner, according to Ralph Seymour and his diorama.

In 1924, as Gellatly began to explore options for donating his collection, he expanded it so prodigiously with purchases of old master paintings, Italian woodcarvings, and Chinese glassware that his townhome could no longer contain them. He rented six rooms in New York’s Heckscher Building and transferred most of his holdings to them, rearranging their contents into harmonious displays. The miniature glass vessels that crowd the desktop in Seymour’s diorama suggest this profusion of objects as well as the clear delight Gellatly took in handling them and using them as the material from which to construct stimulating comparative installations.

To prove what his favorite American artists had achieved, Gellatly explained, “I have surrounded the paintings of the American Renaissance by masterpieces of the world’s art of four thousand years or more, the art of the world is really assembled.” The eccentricities within Gellatly’s collection—as well as its abundance and scale—posthumously landed his name in newspapers around the country and renewed calls among press, politicians, and the public for a dedicated federal art museum building, as the donor had hoped. After his death in 1931, these objects were finally transferred to Washington, DC, and temporarily installed in the United States National Museum (now the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History building).

Seymour’s tribute to Gellatly is in SAAM’s collection thanks to the stipulation that the entire collection must remain intact. Hence the surprising survival of an important survey collection of Italian glass, including antique vessels and previously under-researched specimens of nineteenth-century Venetian art glass, within a museum that today is devoted to American art.

At SAAM, many of these objects remain in storage, including Ralph Seymour’s woebegone Diorama—until now. The exhibition Sargent, Whistler, and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano is displaying these fascinating objects to honor Gellatly’s appreciation for the fine and decorative arts and his vision for his collection.

This story is based on exhibition materials and the accompanying catalogue for Sargent, Whistler, and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano.