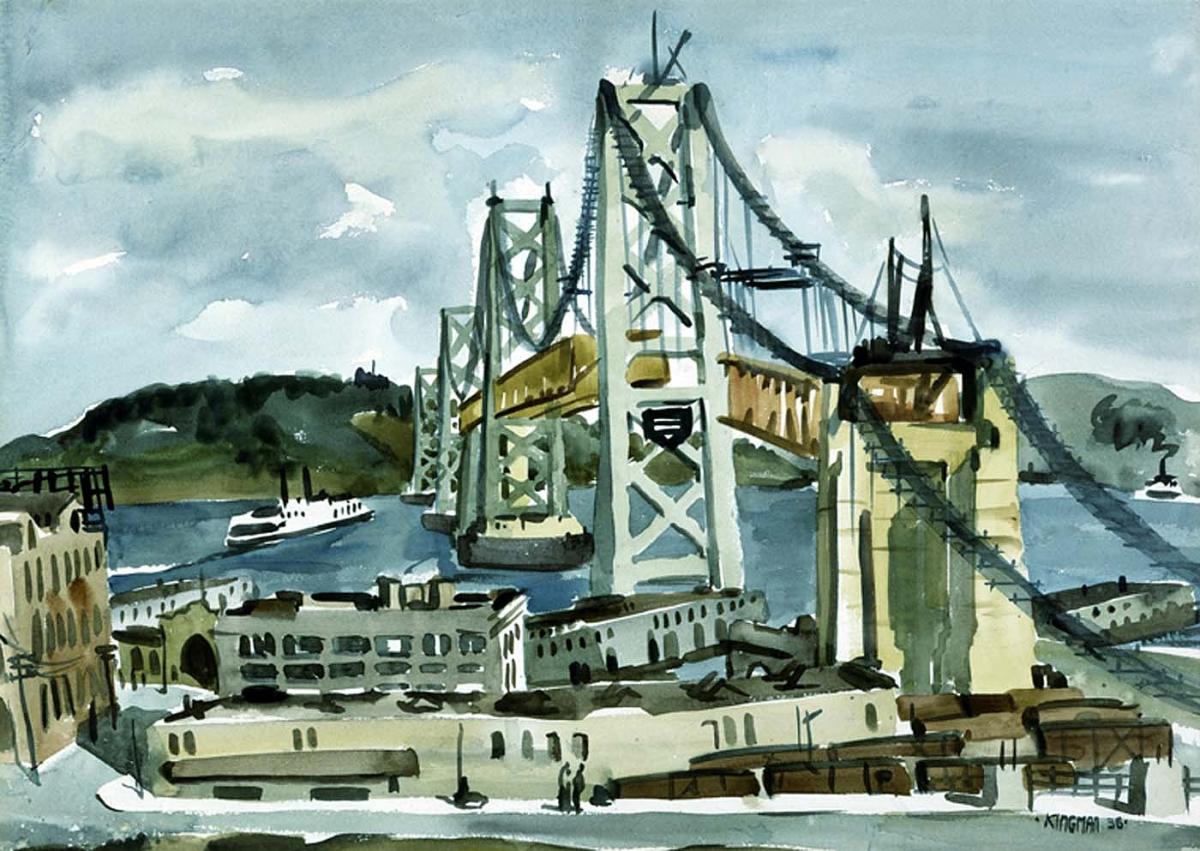

When I stumbled upon Dong Kingman’s Bridge over River (1936), the gleaming sliver towers of a yet-to-be-finished Bay Bridge transported me home. Much of my childhood was spent on that bridge, shuttling back and forth between my grandparents' home in San Francisco and mine in Oakland. I hunched over my computer screen, greedily drinking in every inch of Kingman’s watercolor and yearning for the omurice or chawanmushi that my grandmother would inevitably have waiting for me at the end of my journey across the bridge.

Dong Kingman was an outstanding watercolorist, who, in addition to teaching art at Columbia University and Hunter College, worked for decades as an illustrator in Hollywood, designing set backgrounds for scores of blockbuster films. He also served as a cultural ambassador and international lecturer for the U.S. Department of State. In 1936 Kingman was hired as an artist to work under the auspices of the Federal Arts Project (FAP), The FAP was a branch of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) dedicated to financially supporting thousands of artists across the country who were struggling under the economic and social turmoil of the Great Depression. Yet as with many of the relief programs created by the Roosevelt Administration—from Social Security to Unemployment Insurance—the benefits were unequally distributed. White men benefited most, often at the exclusion of women and people of color. This pattern of exclusion held for many of the federal arts programs.

Kingman was one of the few known Asian American artists to be hired by the WPA. The astounding absence of Asian American artists relative to their white counterparts can be in part explained by the requirement of citizenship, which became a prerequisite for employment by the WPA in 1937, two years after the program’s founding. The histories of Asian Americans are marked by exclusion, most obvious of which is the century-long denial of citizenship for Asian immigrants. Significantly, SAAM’s collection includes the works of other Asian American artists employed by the WPA, most of whom worked for the program before the citizenship requirement was adopted. These artists include Bumpei Usui, Fugi Nakamizo, Isamu Noguchi, Chee Chin S. Cheung Lee, Kenjiro Nomura, Sakari Suzuki, Chuzo Tamotzu, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi. Both Kingman and Noguchi were born in the United States and were thus able to continue to work for the WPA even after the citizenship requirement was adopted by the agency.

To say that I stumbled upon Kingman’s work is not precise; it implies that I encountered it by happenstance. Since coming to SAAM last year as a Luce Curatorial Fellow, I have constantly searched the collection for the presence and the traces of Asian American makers. I do this not because I hope to find the “me stories” in SAAM’s collection (although that is certainly true), but because I know that the histories of Asian American artists open spaces for critical interrogation. These histories unsettle the tidy stories of American art -- a sweeping narrative, dominated by a few artistic geniuses, who are always white and always men, that unfolds from the beautiful landscapes of Albert Bierstadt to sublime color fields of Barnett Newman. These are the histories I learned in college and graduate school and the ones I am trying to grapple with now. I am trying to think beyond and refuse the logics and instructions of art history that taught me what to value as beautiful and who and what to prioritize as subjects worthy of scholarly inquiry.

My abiding companions in this rethinking— the scholars Lisa Lowe, Mae Ngai, Evelyn Nakano Glenn, Michael Omi, Gary Okihiro, Manu Karuka— have helped me understand that absent a deep and layered study of our history, we cannot begin to understand the histories of American and global capitalism, the nature of American imperialism and militarism or how logics of democracy, citizenship, and immigration function in the United States. Studying Kingman and the other Asian American artists of the WPA is not merely about adding them into an existing canon of New Deal artists. The immense joy I find in studying these artists is in the myriad ways their work unsettles our understanding of artistic production during the New Deal period, illuminating the complexities, contradictions, and conflicts that reside at the heart of the stories of American art.

Grace Yasumura, the Luce Curatorial Fellow, earned her Ph.D. in art history and archaeology from the University of Maryland in 2019. Her dissertation examined the different ways racialized identities were created and contested in New Deal post office murals.