The exhibition ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now opened at an incredibly challenging time. The global pandemic delayed its debut for in-person visitors by almost six months, but during this time SAAM hosted a series of virtual conversations with the curators, artists, and scholars involved in the exhibition. The conversations focused on the themes central to ¡Printing the Revolution! and have proven to be vividly relevant to the present moment. Social justice, mentorship, identity, and technology were explored in the thoughtful and engaging five-part Virtual Conversation Series. As the museum prepares to send the exhibition on a multi-city tour of the United States, we’re taking a moment to reflect on moments during the conversations that give us a look into the exhibition and the state of Chicanx graphic arts today.

Throughout the Chicano movement and continuing to the present, artists have used printmaking as a vehicle to debate larger social causes and reflect on issues of their time. In conversation, they told personal stories of their life experiences and their activism, using art to uplift themselves and those around them. “We really believe that art can be an empowering reflection of community struggles, community dreams, and community vision,” states Dignidad Rebelde co-founder Melanie Cervantes. Dignidad Rebelde, along with many of the artists and collectives featured in the exhibition, create art with a sense of urgency—art that calls for equality and social justice. Their activism is inclusive and brings women, Afro Latinx, LGBTQ+, and other previously marginalized voices to the foreground.

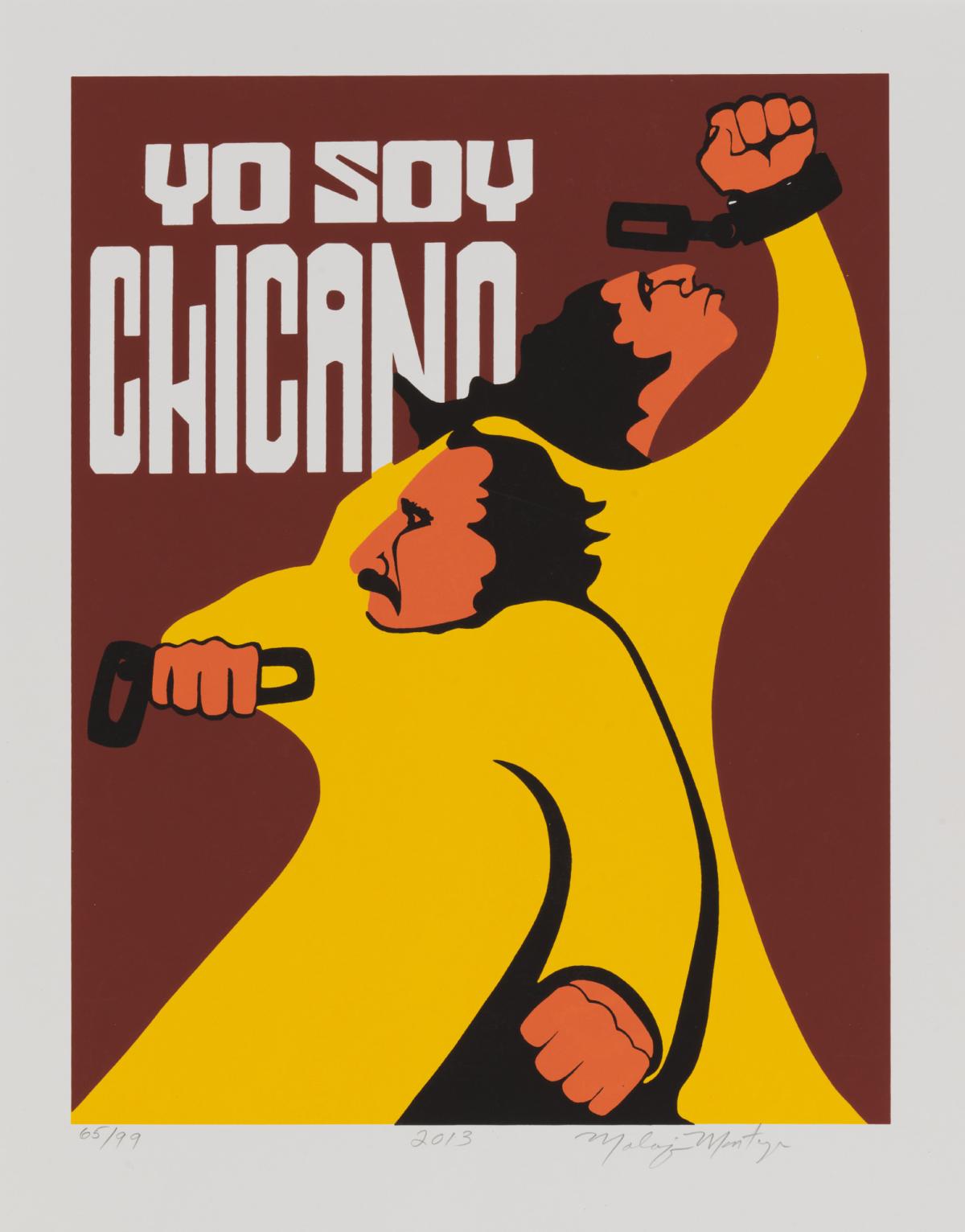

Artists in ¡Printing the Revolution! express a desire to be seen. Malaquías Montoya described the importance of the political and cultural consciousness among people of Mexican descent in the United States during of the rise of the Chicano civil rights movement in the 1960s and 1970s. For Montoya, the term “Mexican American” was ambiguous and the split heritage diluted, rather than strengthened, the sense of self. “We started calling ourselves 'Chicano'” he passionately describes, “and, all the sudden, I was somebody."

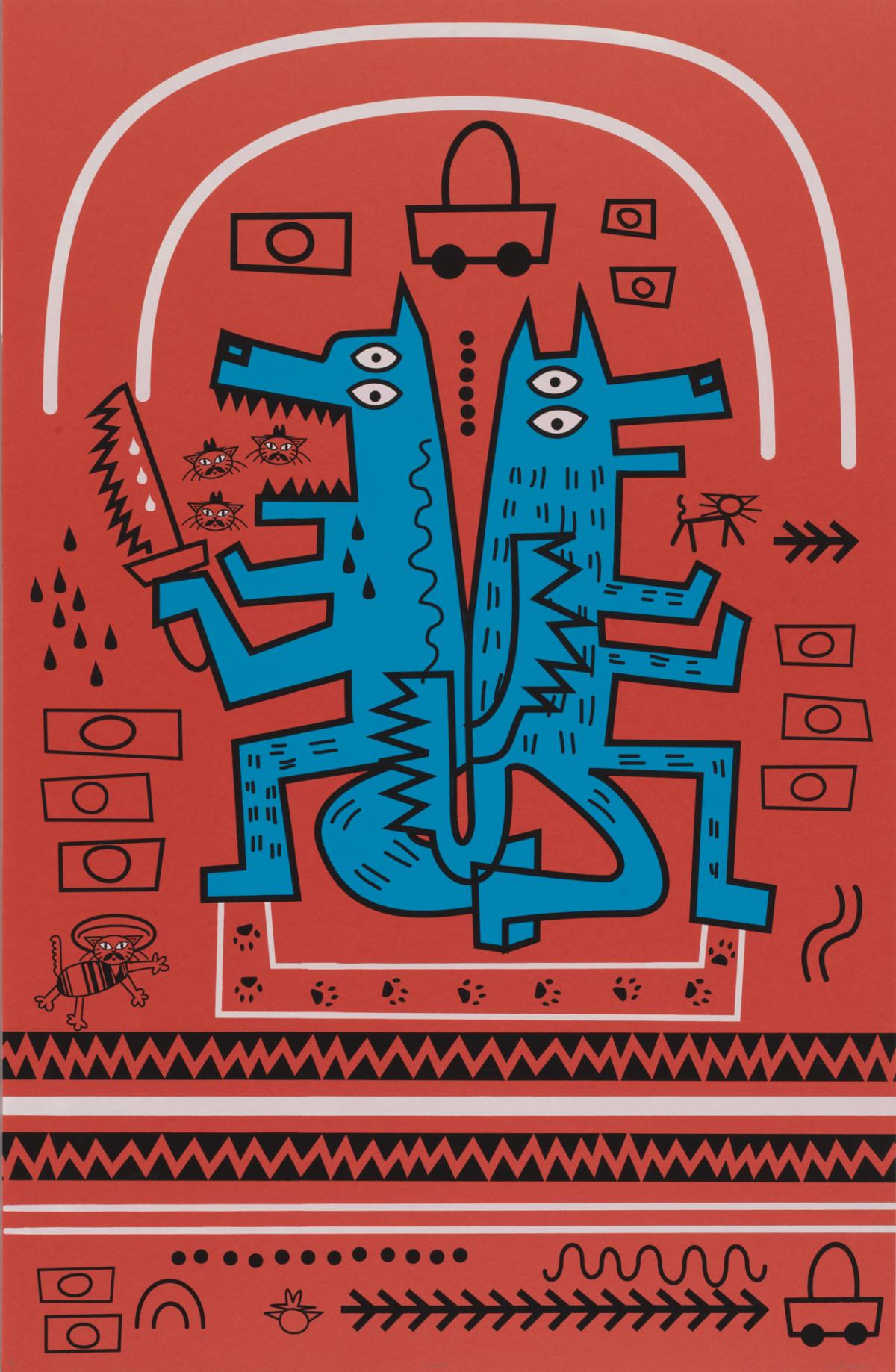

Several artists in the exhibition use innovative technology to push graphics beyond the traditional prints on paper. Michael Menchaca and Julio Salgado discussed the use of digital technology to speed up the creative process. Urgent images convey immediate messages. “Through the digital,” Menchaca explains, “I could express a frustration that was there all the time. And the more I learned about the oppression of Mexican Americans and Latinx folk in the U.S. and wanting to put those invisible histories and make them visible.”

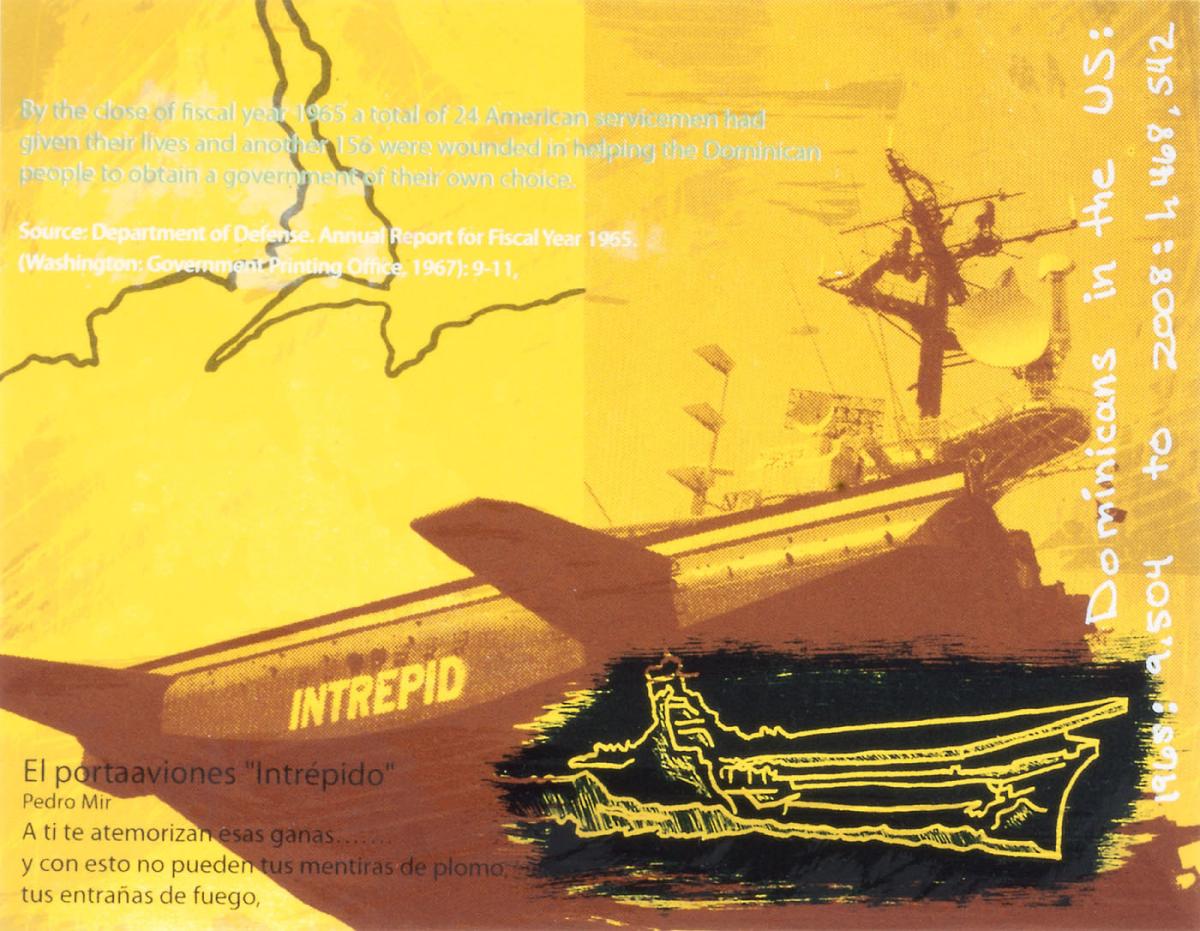

As with the Chicano movement itself, the cornerstone of ¡Printing the Revolution! is the focus on cross-generational mentorship and the passing of knowledge to make the invisible visible. The exhibition is the first to consider how Chicanx mentors, print centers, and networks nurtured other artists. It goes beyond the boundaries of the Chicanx community to those who learned and drew inspiration from the example of Chicanx printmaking. One such artist who drew from the influence of Chicanx printmakers was Pepe Coronado, founder of Coronado Print Studio and founding member of the Dominican York Proyecto GRAFICA. He discussed the essential role of mentorship to push a movement forward. “These young artists can come in and talk and the older, more established artists, can share these experiences,” he explains. “And that’s really crucial for any kind of message to stay alive…with the hope that this message is going to take a new form based on the new generation.”

Archived recordings of the conversation series are available on SAAM’s website.