In the exhibition catalogue for ¡Printing the Revolution!, curator E. Carmen Ramos discusses the ways in which artists, especially printmakers, were central to the rise of a new Chicano identity for Mexican Americans in the 1960s and 1970s. They re-envisioned traditional Mexican celebrations, such as the Day of the Dead and the Fiesta del Maiz, and used them as platforms for elaborate community events to raise awareness for unfair labor practices, anti-immigration policies, and other social justice causes. In an effort to reclaim cultural heritage, they integrated indigenous symbols into their artwork and staged reenactments of Mesoamerican rituals during their events.

Artist and activist Carmen Lomas Garza was central to the early Chicano Movement. Known for her narrative style, Garza chronicles intimate Chicano daily life scenes based on remembrances of her own childhood in Kingsville, Texas, in the 1950s and 1960s. Her consciously folk art–styled works make visible communal and spiritual traditions that both record gendered and intergenerational roles and relations, viewing women as the “translators of the culture.” Through her personal scenes, she brings to light a universe of borderland culture rarely acknowledged as part of the American experience.

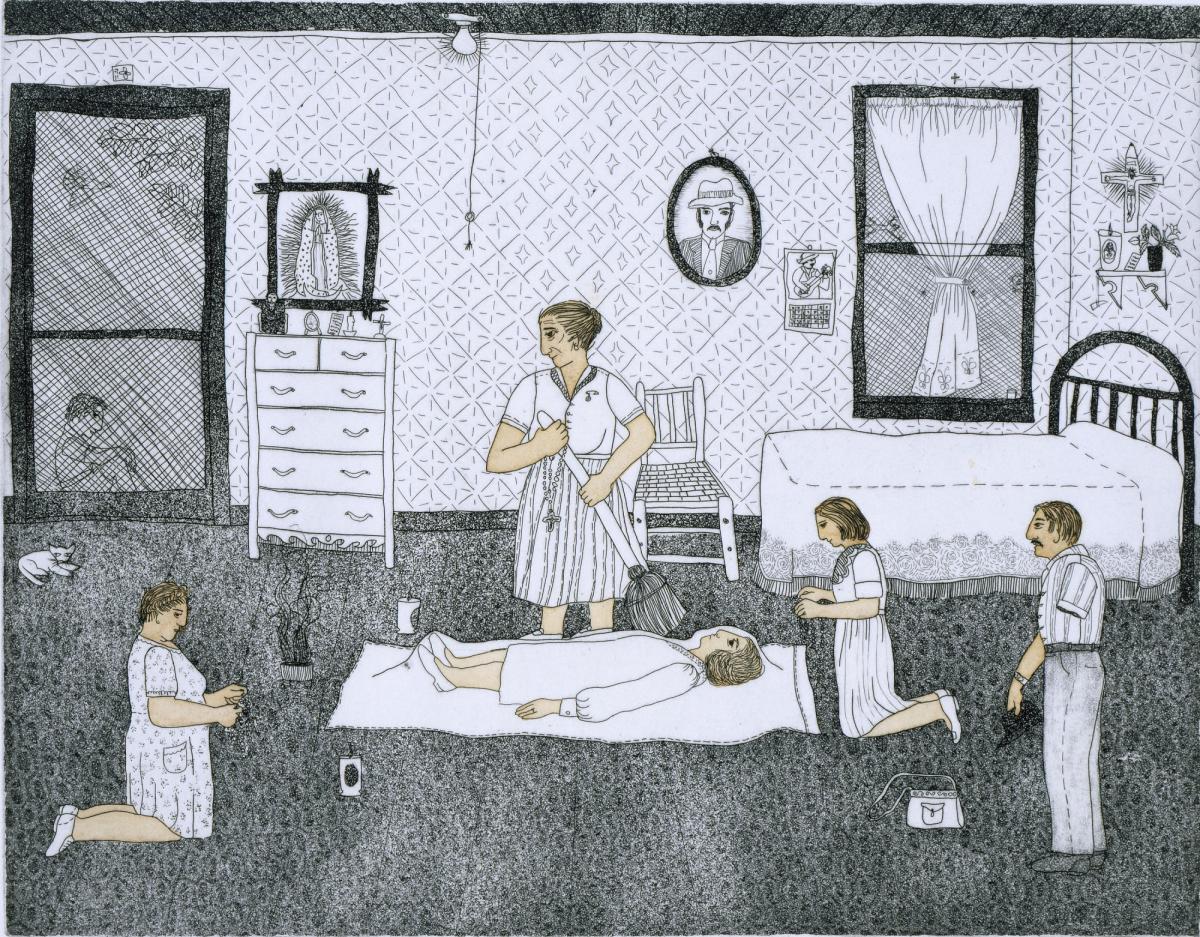

In La Curandera (the healer), Garza pictures a spiritual cleansing ritual using folkloric remedies known as a limpia. The delicate etching documents traditions that incorporate indigenous practices, such as the burning of copal (tree resin) incense seen at the foot of the supine figure. Healing is a reoccurring theme in Garza’s artwork. Faced with corporal punishment as a young student for speaking Spanish at school, Garza turned to art to “heal the wounds inflicted by discrimination and racism.” She has described art as having the ability to soothe “in the same way as the salvila (aloe vera) plant when its cool liquid is applied to a burn or an abrasion.”

Using elements of everyday life, Garza, like other Chicano artists in the early movement, sought to draw from collective memory and create a sense of shared community while also inserting Chicano heritage into a broader American culture.

SAAM’s landmark exhibition, ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now, explores how Chicanx artists have linked innovative printmaking practices with social justice. This blog post is part of series that takes a closer look at selected artworks with material drawn from exhibition texts and the catalogue.