Alma Thomas

Alma Thomas with her portrait by Laura Wheeler Waring, Portrait of a Lady (1947, SAAM) in her home, Washington, DC, 1968. Photo by Ida Jervis. Alma Thomas papers, circa 1894-2001, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- Also known as

- Alma Woodsey Thomas

- Alma W. Thomas

- Born

- Columbus, Georgia, United States

- Died

- Washington, District of Columbia, United States

- Biography

“I’ve never bothered painting the ugly things in life. People struggling, having difficulty. You meet that when you go out, and then you have to come back and see the same thing hanging on the wall. No. I wanted something beautiful that you could sit down and look at. And then, the paintings change you.”

–– Alma Thomas, ca. 1977–78

Alma Thomas was a teacher and artist who developed a powerful form of abstract painting late in life. From the mid-1960s, she produced brilliantly colored and richly patterned works intimately connected to the natural world.

Thomas was raised in a household that emphasized culture and learning. In 1907, her family moved to Washington, DC, in search of greater educational opportunities and relief from racial violence in the South. In 1924, Thomas became Howard University’s first fine arts graduate, encouraged by the art department’s founding professor, James V. Herring. She then began an esteemed thirty-five-year teaching career at Shaw Junior High School. In addition, Thomas earned an MA in arts education at Columbia University in 1934 and studied art at American University during the 1950s. A significant figure in Washington’s art world, Thomas was associated with the Little Paris Group of artists and Howard University’s Gallery of Art. She was also instrumental in the 1943 formation of the cutting-edge Barnett Aden Gallery, among the first Black-owned galleries in the United States.

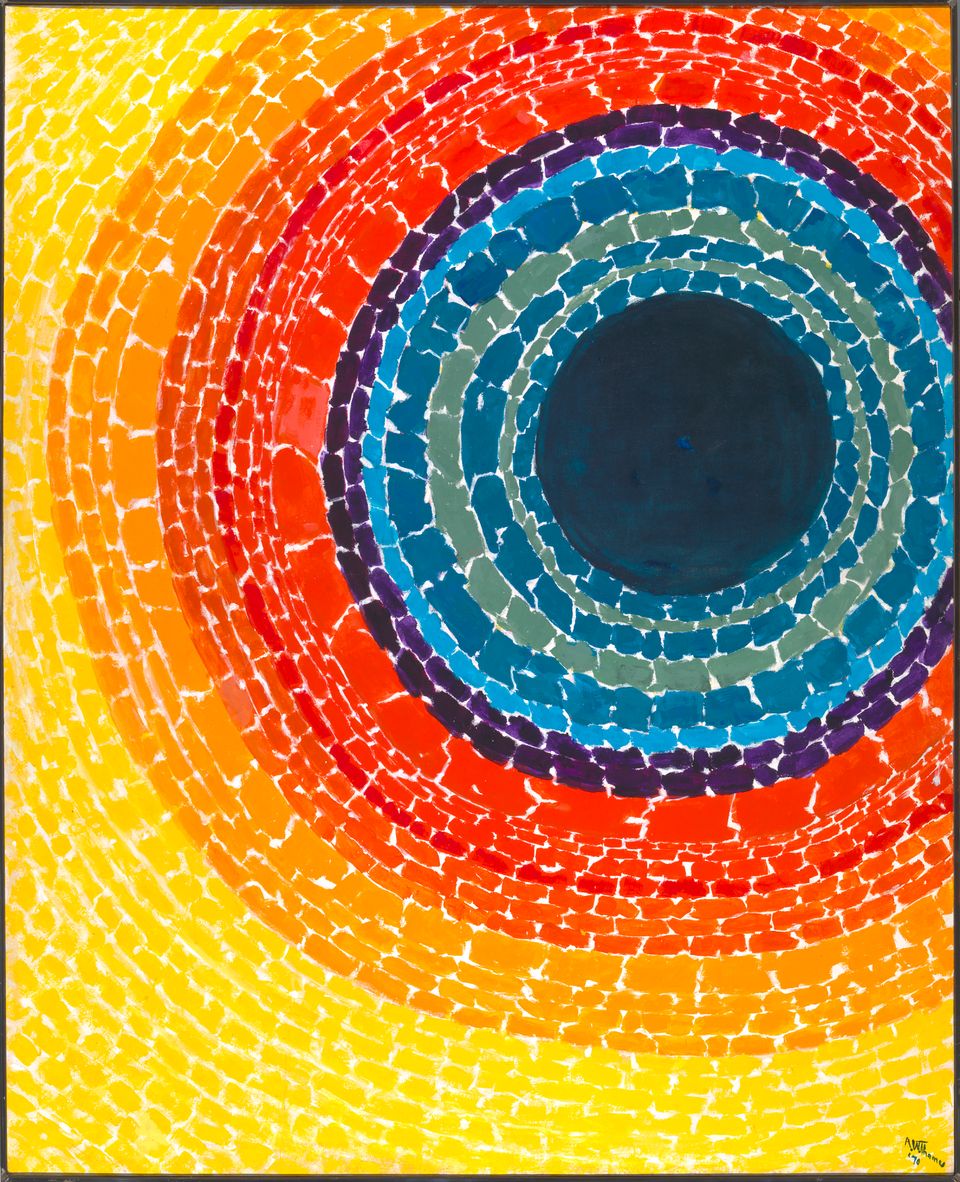

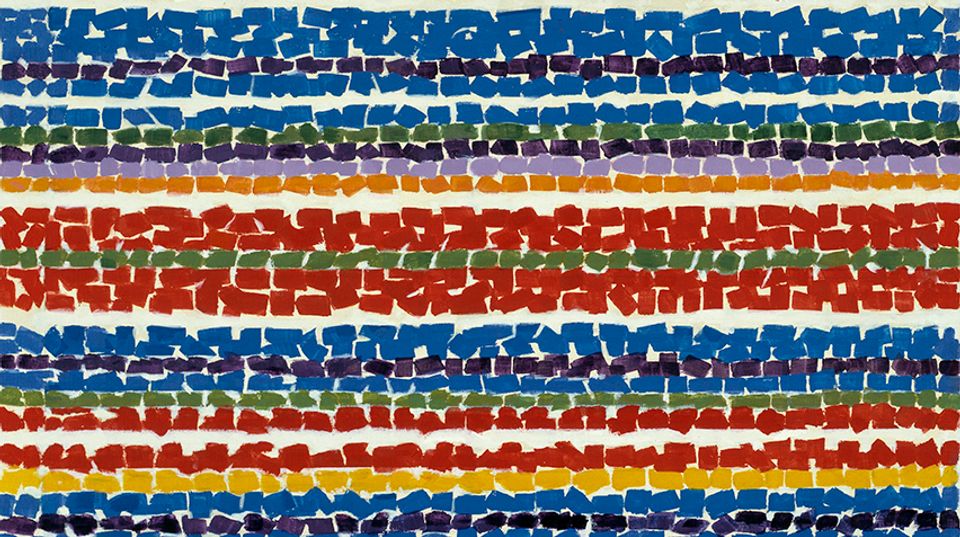

A talented representational artist, Thomas moved toward abstraction in the 1950s with works like The Stormy Sea (1958, SAAM), but she arrived at her signature style only after retiring in 1960. Spurred by the prospect of a 1966 exhibition at Howard, Thomas began painting with small daubs of vibrant colors arranged in rhythmic patterns, as in Light Blue Nursery (1968, SAAM). With these works, she charted a new path, inventively drawing on artistic practices ranging from French twentieth-century artist Henri Matisse and Bauhaus artist and color theorist Johannes Itten to local artists and peers, including painter and Howard professor Loïs Mailou Jones and abstract painters of the Washington Color School. Thomas consistently found inspiration in nature, as in paintings like Aquatic Gardens (1973, SAAM). Washington’s parks, the garden beyond her kitchen-studio, and memories of roses around her childhood home all proved vital touchstones. Scientific advances, especially early space travel and the new vantage points of Earth it afforded, also impacted Thomas’s work, as in Snoopy–Early Sun Display on Earth (1970, SAAM). Though Thomas attended the 1963 March on Washington, creating three related works, her practice and its attention to color did not overtly engage the civil rights movement. Instead, she emphasized beauty’s restorative power: “Through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.”

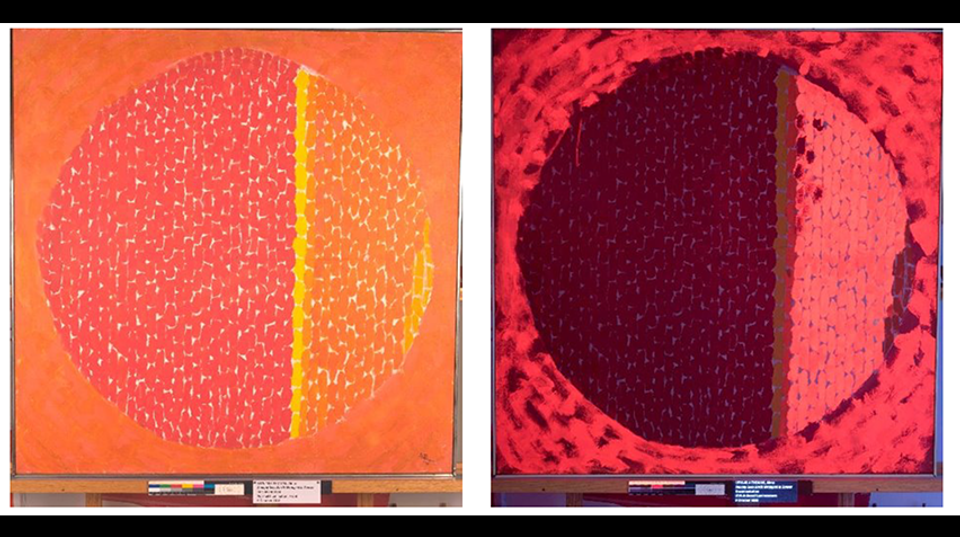

Thomas’s post-retirement paintings earned tremendous critical praise—no small feat for an artist outside New York City. In 1972, she became the first Black woman to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, presenting The Eclipse (1970, SAAM) and Antares (1972, SAAM), among others. Around then, Thomas reflected on her segregated childhood: “One of the things we couldn’t do was go into museums, let alone think of hanging our pictures there. My, times have changed. Just look at me now.”

Authored by Katherine Markoski, American Women’s History Initiative Writer and Editor, 2024.

- Primary Artist Biography

During the 1960s Alma Thomas emerged as an exuberant colorist, abstracting shapes and patterns from the trees and flowers around her. Her new palette and technique—considerably lighter and looser than in her earlier representational works and dark abstractions—reflected her long study of color theory and the watercolor medium.

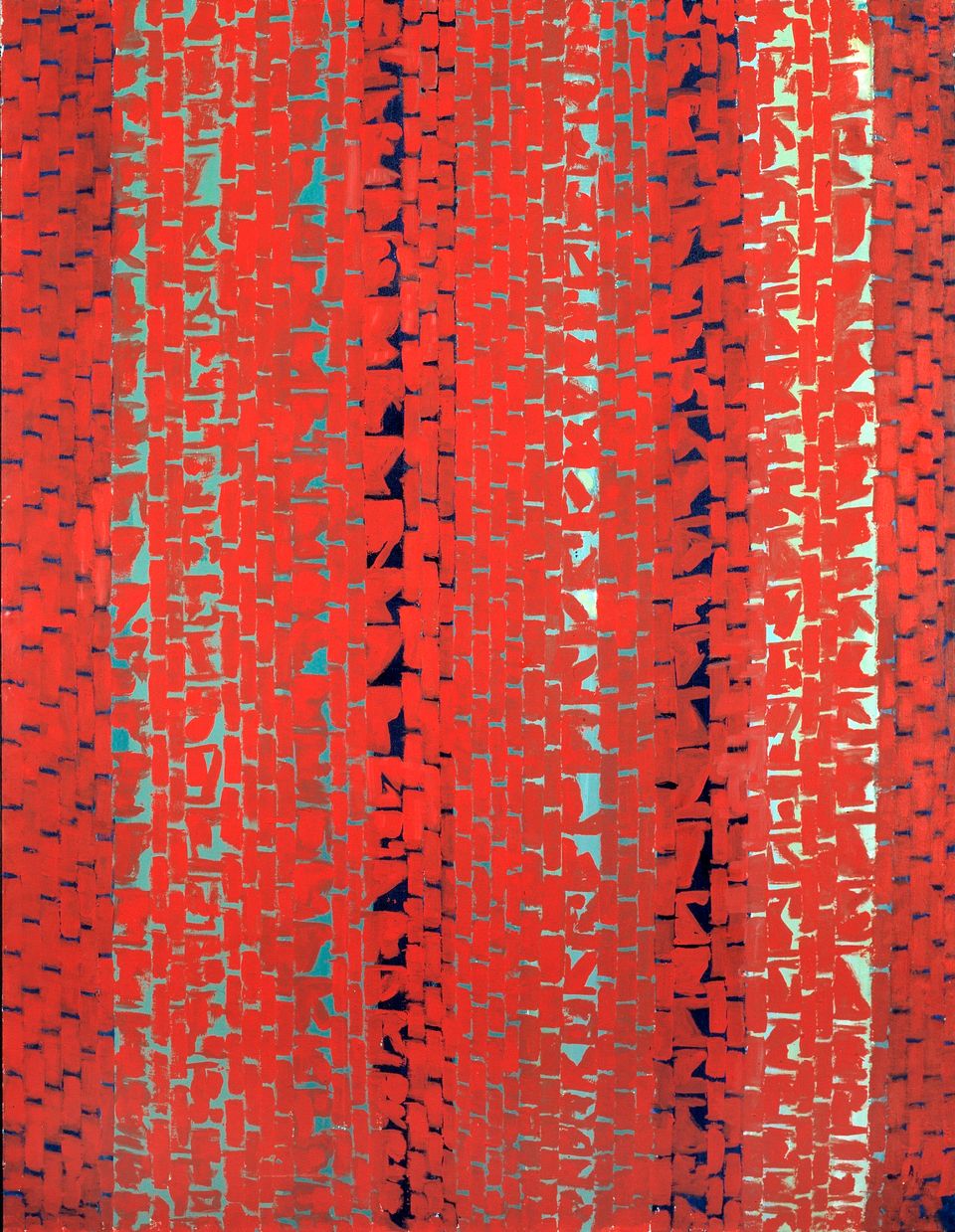

Red Sunset, Old Pond Concerto [SAAM, 1977.48.5] emphasizes the intensity of a sunset as it overtakes a landscape, penetrating layers of greenery to strike darkening water. Broken rows of color pats, a hallmark of her mature style, alternate with emphatic vertical bands. Their irregular intervals create a visual rhythm akin to music, while dappled reds, greens, and blue-blacks orchestrate subtle nuances and dramatic contrasts. Thomas frequently talked about "watching the leaves and flowers tossing in the wind as though they were singing and dancing." She also liked to imagine seeing natural forms from a plane. Her lyrical interpretation of a pond at sunset suggests a blending of these two perspectives.

As a black woman artist, Thomas encountered many barriers; she did not, however, turn to racial or feminist issues in her art, believing rather that the creative spirit is independent of race or gender. In Washington, D.C., where she lived and worked after 1921, Thomas became identified with Morris Louis, Gene Davis, and other Color Field painters active in the area since the 1950s. Like them, she explored the power of color and form in luminous, contemplative paintings.

Lynda Roscoe Hartigan African-American Art: 19th and 20th-Century Selections (brochure. Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art)

Artist Biography"Man's highest aspirations come from nature. A world without color would seem dead. Color is life. Light is the mother of color. Light reveals to us the spirit and living soul of the world through colors."—Press Release, Columbus Museum of Arts and Sciences, 1982, for an exhibition entitled A Life in Art: Alma Thomas 1891–1978, Vertical File, Library, National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Alma Thomas began to paint seriously in 1960, when she retired from her thirty-eight year career as an art teacher in the public schools of Washington, D.C. In the years that followed she would come to be regarded as a major painter of the Washington Color Field School.

Born on September 22, 1891, in Columbus, Georgia, Thomas was the eldest of four daughters. Her father worked in a church and her mother was a seamstress and homemaker. Thomas's family was well respected in Columbus, and she and her sisters grew up in comfortable surroundings. The family lived in a large Victorian house high on a hill overlooking the town where Thomas spent her childhood observing the beauty and color of nature. In 1907, when Thomas was fifteen years old, her father moved the family to Washington, D.C. She enrolled in Howard University, and in 1924 became the first graduate of its newly formed art department. Thomas's teacher and mentor, James V. Herring, granted her use of his private art library, from which she gained a thorough background in art history. A decade later, she earned a Master of Arts degree in education from Columbia University.

During the 1950s Thomas attended art classes at American University in Washington. She studied painting under Joe Summerford, Robert Gates, and Jacob Kainen, and developed an interest in color and abstract art. Throughout her teaching career she painted and exhibited academic still lifes and realistic paintings in group shows of African-American artists. Although her paintings were competent, they were never singled out for individual recognition.

Suffering from the pain of arthritis at the time of her retirement, she considered giving up painting. When Howard University offered to mount a retrospective of her work in 1966, however, she wanted to produce something new. From the window of her house she enjoyed watching the ever-changing patterns that light created on her trees and flower garden. So inspired, her new paintings passed through an expressionist period, followed by an abstract one, to finally a nonobjective phase. Many of Thomas's late-career paintings were watercolors in which bold splashes of color and large areas of white paper combine to create remarkably fresh effects, often accented with brush strokes of India ink.

Although Thomas progressed to painting in acrylics on large canvases, she continued to produce many watercolors that were studies for her paintings. Thomas's personalized mature style consisted of broad, mosaic-like patches of vibrant color applied in concentric circles or vertical stripes. Color was the basis of her painting, undeniably reflecting her life-long study of color theory as well as the influence of luminous, elegant abstract works by Washington-based Color Field painters such as Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, and Gene Davis.

Thomas was in her eighth decade of life when she produced her most important works. Earliest to win acclaim was her series of Earth paintings—pure color abstractions of concentric circles that often suggest target paintings and stripes. Done in the late 1960s, these works bear references to rows and borders of flowers inspired by Washington's famed azaleas and cherry blossoms. The titles of her paintings often reflect this influence. In these canvases, brilliant shades of green, pale and deep blue, violet, deep red, light red, orange, and yellow are offset by white areas of untouched raw canvas, suggesting jewel-like Byzantine mosaics.

Man's landing on the moon in 1969 exerted a profound influence on Thomas, and provided the theme for her second major group of paintings. In 1969 she began the Space or Snoopy series so named because "Snoopy" was a term astronauts used to describe a space vehicle used on the moon's surface. Like the Earth series these paintings also evoke mood through color, yet several allude to more than a color reference. In Snoopy Sees a Sunrise of 1970, she placed a circular form within the mosaic patch of colors and accented it with curved bands of light colors. Blast Off depicts an elongated triangular arrangement of dark blue patches rising dramatically and evocatively against a background of pale pinks and oranges. The majority of Thomas's Space paintings are large sparkling works with implied movement achieved through floating patterns of broken colors against a white background.

In her last paintings, Thomas employed her characteristic short bars of color and impasto technique. The tones, however, became more subdued, and the formerly vertical and horizontal accents of Thomas's brush strokes became more diverse in movement, and included diagonals, diamond shapes, and asymmetrical surface patterns. During the artist's final years, the crippling effects of arthritis prevented her from painting as often as she wanted.

Alma Thomas never married, and lived in the same house her father bought in downtown Washington in 1907. The final years of her life brought awards and recognition. In 1972 she was honored with one-woman exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art and at the Corcoran Gallery of Art; that same year one of her paintings was selected for the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Before her death in 1978, Thomas had achieved national recognition as a major woman artist devoted to abstract painting.

Regenia A. Perry Free within Ourselves: African-American Artists in the Collection of the National Museum of American Art (Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art in Association with Pomegranate Art Books, 1992)

Videos

Exhibitions

Related Books

Related Posts