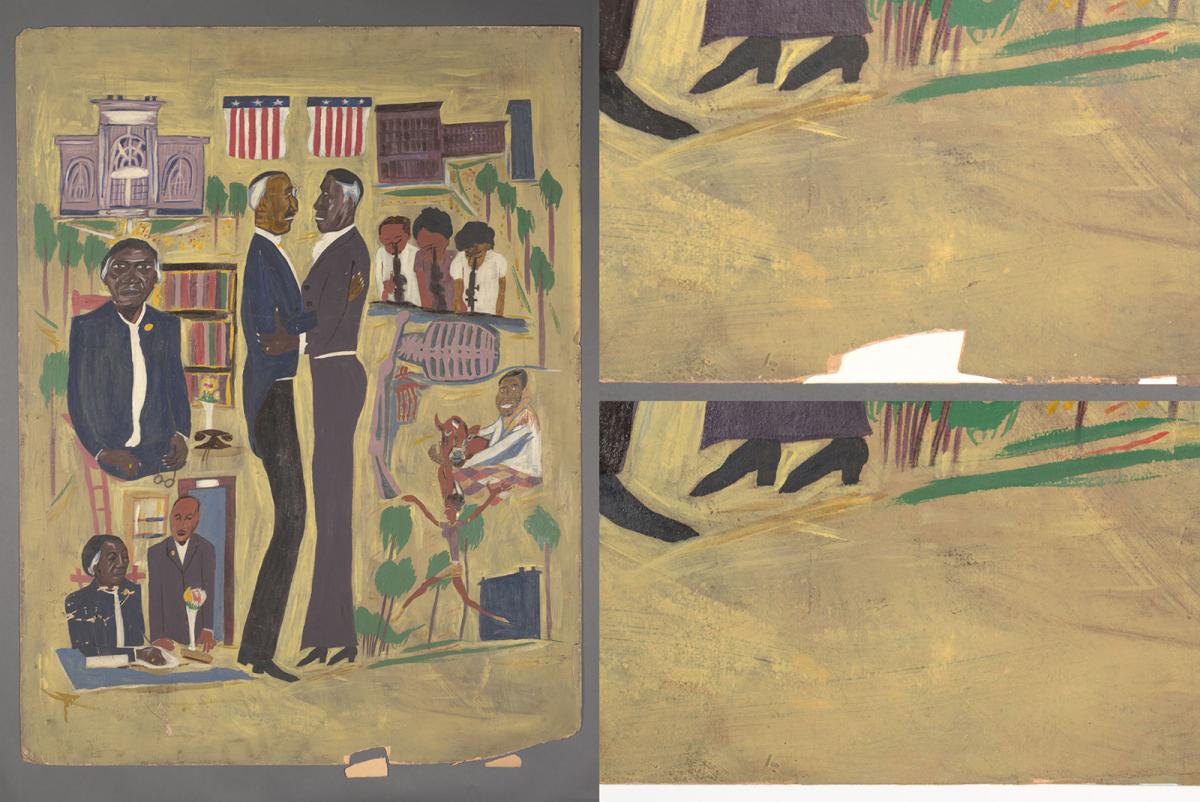

Keara Teeter treating William H. Johnson’s Historical Scene with Mary McLeod Bethune, ca. 1945, oil on paperboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Harmon Foundation. Photo by Lou Molnar

Keara Teeter, Samuel H. Kress fellow in paintings conservation (2019–2020), has been hard at work at the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Lunder Conservation Center, conducting a condition survey and conservation treatments of the Fighters for Freedom series in preparation for an upcoming traveling exhibition. Explore the series through her lens.

There are Americans who have spent their lives fighting for measurable change for civil rights issues. From artistic prints reproduced in William Still’s book, The Underground Rail Road (1886), to the 1940–1970s photojournalism of Gordon Parks, art has been a powerful tool to document, commemorate, and encourage change going forward. William H. Johnson’s Fighters for Freedom paintings reference images by Still, Parks, and others as a method of re-depicting important historical scenes and celebrating them through a new artistic medium.

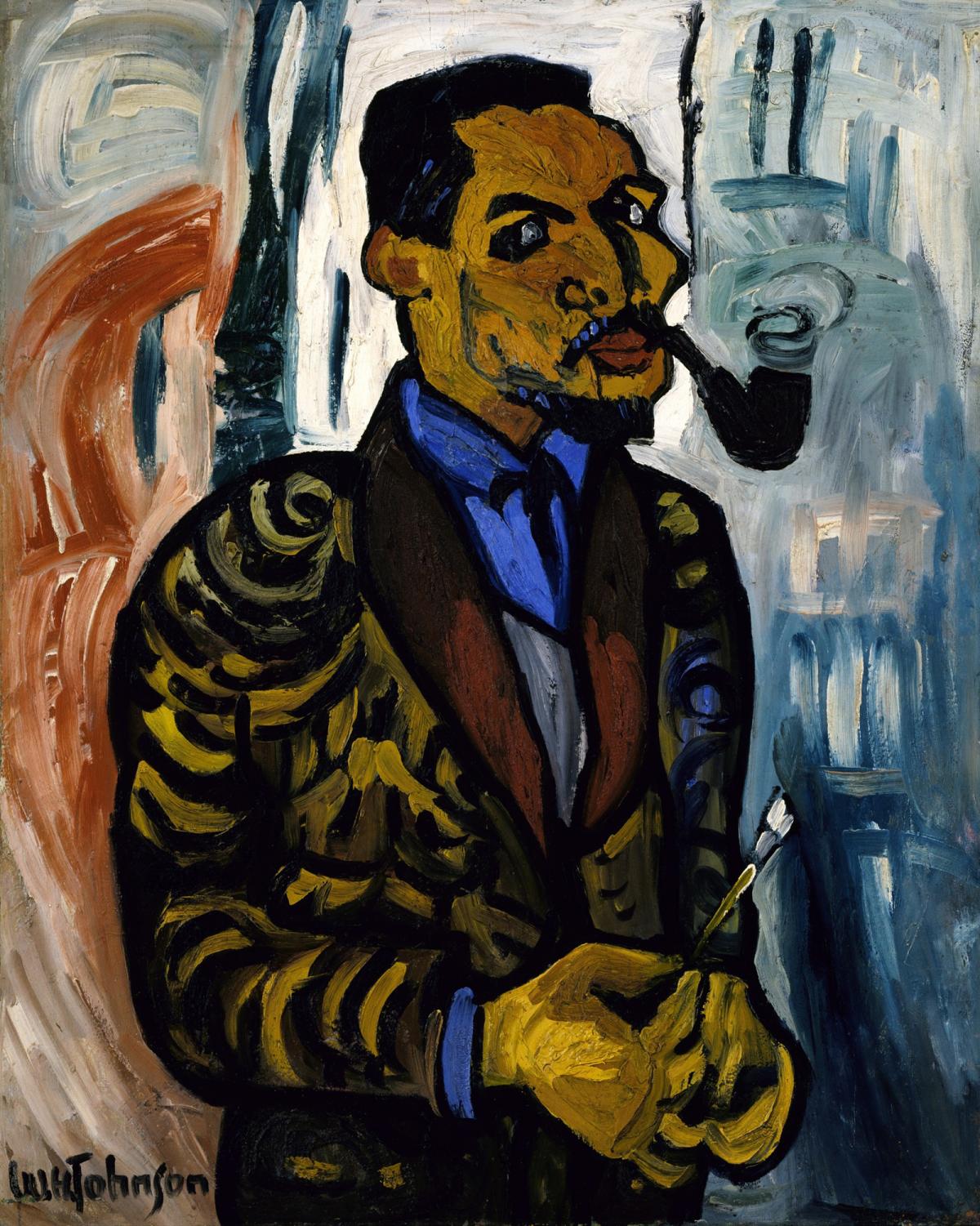

William H. Johnson, Self-Portrait with Pipe, ca. 1937, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, 1967.59.913

William H. Johnson (1901–1970) was born in South Carolina and moved to New York City as a teenager. He financed his own training at the prestigious National Academy of Design and became one of their most talented students. His achievements, however, were not always recognized. In his final year at the Academy, Johnson was turned down from the school’s Pulitzer Traveling Scholarship. Outraged by this decision, one instructor personally fundraised $1,000 to finance Johnson’s travel to study in Paris. Beginning in France, the young artist lived and traveled throughout Europe and North Africa for over a decade before returning to the United States. By 1945, having determined to “paint his own people” Johnson began creating the Fighters for Freedom series, shining a light on luminaries including Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Crispus Attucks, and Mary McLeod Bethune. This series—along with over 1,000 of Johnson’s other drawings, paintings, and prints—and entered the national collection, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 1967.

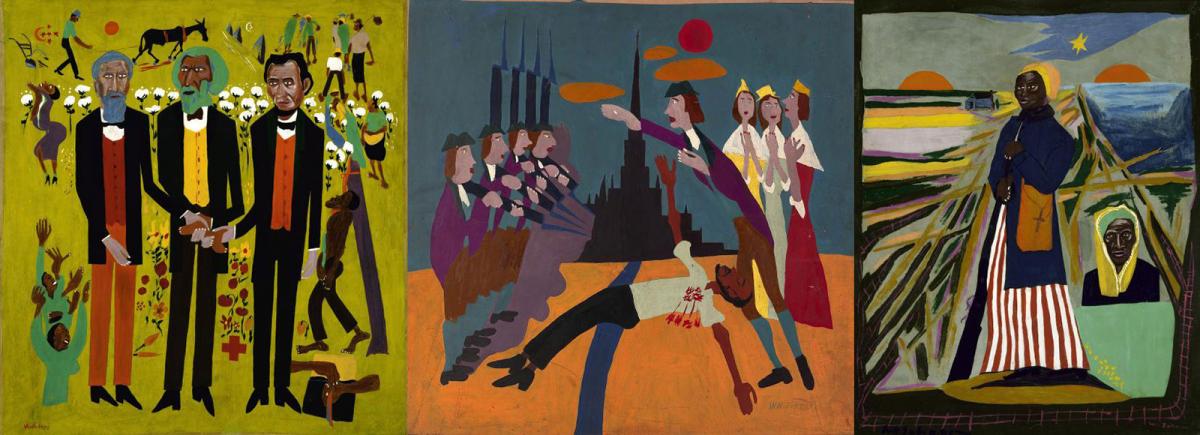

Examples of three paintings from William H. Johnson's Fighters for Freedom series (left to right): Three Great Abolitionists: A. Lincoln, F. Douglass, J. Brown (ca. 1945), Crispus Attucks (ca. 1945), and Harriet Tubman (ca. 1945).

For my fellowship, I began surveying the entire series back in September and found that 26 of the 29 paintings in the series for the exhibition required conservation treatment. This was somewhat unsurprising given that, before coming to SAAM’s collection, the paintings had crossed the Atlantic Ocean twice. As an art conservator, it has been an exciting challenge to deal with the variety of condition issues from water staining to paint loss and structural damages in the solid supports (paperboard, plywood, Masonite, etc.). Each treatment is unique. I must carefully choose which conservation materials are appropriate and ask:

- Does this painting require structural stabilization and how can the composition be visually brought back together?

- Can my additions be easily removed in the future without damaging the original artwork?

- Will my palette remain lightfast or will the colors fade or darken over time?

- If a new frame is required, how can it help reduce direct handling of the artwork in the future?

Treatment began by removing surface dirt and addressing major structural problems, such as replacing missing corners, stabilizing tears, and filling losses. Next, I turned to address aesthetic concerns such as retouching paint loss.

Stages of conservation treatment for Historical Scene with Mary McLeod Bethune (ca. 1945). The entire painting is shown before treatment (left) with details of a rag board fill along the bottom edge (top right) and that same area after inpainting had been completed (bottom right).

Beyond returning the paintings to their original appearance, the most fulfilling aspect in treating this series has been uncovering new information about the artist, his travels, and his use of materials. On the backside of some Johnson paintings, I found manufacturer's stamps (see image of Upson Board below) and shipping labels that were added during one of the artist’s transatlantic voyages. On the front of many artworks, I found sketches Johnson had added in graphite pencil before he began painting in color.

Detail of the “UPSON BOARD Co” stamp on the reverse of Booker T. Washington Revelation (ca. 1945). The area is shown as observed with the naked eye (top left) and with digital annotation (bottom left). Upson Board was advertised The Rotarian and other magazines (right) to encourage New Yorkers to “Upsonize” their homes.

By preserving these artworks today, the artist’s message will continue to inspire future generations and elicit meaningful dialogue about the meaning of freedom. With the current Black Lives Matter movement and George Floyd protests, I think about who else Johnson might have chosen to include in his Fighters for Freedom series if he were still alive today. Although my work with SAAM is just one part of a larger story, preserving this influential series is a snapshot into the enduring power of art. To learn more about Johnson’s poignant artwork, read The Washington Post’s recent article about SAAM’s Moon Over Harlem and the Archives of American Art Journal’s 2019 article about SAAM’s William H. Johnson history paintings.

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions off, selected

This is a modal window.

See how art conservators preserve and protect the paintings in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s collection from the effects of time.

On Thursday, November 5, 2020, Keara Teeter, a 2019–2020 Samuel H. Kress Fellow in Paintings Conservation, discussed the conservation treatment of William H. Johnson’s iconic Fighters for Freedom paintings. Created 75 years ago, this series celebrates prominent Black Americans who fought for civil rights.

Welcome, everyone. We're so happy to have you all here. If this is your first Converse with a Conservator, this is a monthly discussion, discussion-based program I should say, that's driven by your questions, so that means that officially, "The art doctor is in." So since this is being recorded, your audio and video will be turned off, so please use the Q&A section, and we will get through as many questions as we can in these 45 minutes. It goes by really quickly. I also wanted to point out that we are offering the closed-captioned option, and that is located in the Zoom toolbar below. And additionally, please don't close out your internet browser because at the end of the program there's a very brief survey that will help us, help inform us, for our future programs. Next slide here. I would also like to point out that we want to gratefully acknowledge the diverse and vibrant Native communities who make their homes here in Washington, D.C., the Native peoples on whose ancestral homelands the museum has gathered, and the labor of people who were enslaved in constructing SAAM's historic building. Next slide. So speaking of the building, if you haven't yet been to the Lunder Conservation Center at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, or SAAM as we like to abbreviate it, it is the first visible conservation lab on permanent display at an art museum. So I, Laura Hoffman, as the Program Manager, work on these on creating programs both in person and now online all about conserving and preserving America's artworks. Without further ado, let's get right into it, and we're going to get into tonight's topic which is William H. Johnson's "Fighters for Freedom" series with Lunder Conservation fellow, Keara Teeter. I do want to note that some of Williams H. Johnson's paintings do contain graphic content, so viewer discretion is advised. So to kick us off, Keara, will you tell us a little bit about yourself and how you got started here at Smithsonian American Art Museum?

- (Keara Teeter) Absolutely. Hello, everyone, and welcome. My name is Keara Teeter, and I started at SAAM as a graduate student intern when I was in my third and final year at the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation, and after I graduated I stayed on as a fellow, and so I have been working on the William H. Johnson "Fighters for Freedom" series as part of my fellowship, which for those of you who may be unfamiliar with what a fellowship is, it's kind of like a postgraduate academic appointment where you focus on a specific project, and so the "Fighters for Freedom" project is my project.

- (Laura Hoffman) Great. And you've been with us since...is it 2018?

- (Keara Teeter) Yes.

- (Laura Hoffman) Great. And I know that know you've been working on this project, but for some of us who might not be aware or familiar with William H. Johnson, can you give us a little brief synopsis about who he was?

- (Keara Teeter) So William H. Johnson was an African American painter who he was born in South Carolina, and he moved to New York where he studied at the National Academy of Design, and you can actually see the left image on this slide is a self-portrait that he painted while he was at the academy. And then he ended up after graduating moved to Europe and spent about ten years living in Europe and North Africa traveling around for shows before actually returning to the United States.

- (Laura Hoffman) And I'm curious about his work. How many do we have here at SAAM?

- (Keara Teeter) So we have about 1,200 drawings, prints, and paintings, and the "Fighters for Freedom" series is a subset of the paintings that he created, and here's just a very brief overview. Here's three examples of paintings from the "Fighters for Freedom" series, but I've been looking at 29 paintings for this exhibition, so this is just, you know, a very small subset.

- (Laura Hoffman) Do you know how many paintings there are in the "Fighters for Freedom" series, like approximately?

- (Keara Teeter) For, like, the total series, I don't actually have that number, but there were 29 selected for this exhibition, so that's what my focus has been on.

- (Laura Hoffman) Mhm, great. And I see you've pulled out right here, you've got three different examples. Are these all ones that you have looked at, worked on?

- (Keara Teeter) I have looked at all of these, so I have not worked on all three of these yet, but as part of...here, I'm going to scroll ahead here. As part of my initial survey of the series and of the condition, I actually did go and look at all of them, so some of the paintings are on display in the museum, and so visitors of the museum can see them in person, but a lot of them are in museum storage, and so I actually went out to museum storage to look and assess the condition of a lot of these. And this is just an example of a condition map that I created for one of them showing some of the damages and the losses.

- (Laura Hoffman) So did you find anything unexpected in these condition survey of these 29 pieces?

- (Keara Teeter) I did for some pieces. Probably the most exciting thing was one painting had on the backside a couple of shipping labels adhered to the back of the painting, and those labels, one was written in English, and one was written in Swedish, and they actually documented and outlined his path from New York to Copenhagen in 1946 where he basically, not only did he travel, but he actually shipped his artwork with him in the cargo hold of the ship and brought it over to Europe with him.

- (Laura Hoffman) Oh, wow. And just so people also have a reference of it, you mentioned that it was in the 1940s. Can you just share with us his life dates so we get a sense of when he did the specific series within his whole lifetime?

- (Keara Teeter) Sure. So he started, when he was in the Academy, he graduated in 1926, and so that was really the very early stage of his career. When he came back to the U.S. that was 1938, so that was right before the World War, and then he was creating these paintings in, like, circa 1944 or 1945, and so that was actually at the very, very end of his artistic career because after he created these paintings he did live for a while longer, but he wasn't actively creating and exhibiting art in the latter part of his life.

- (Laura Hoffman) And I believe that he, his life dates, were 1910...or, I'm sorry, 1901 to 1970? Is that...

- (Keara Teeter) Yes.

- (Laura Hoffman) Okay. Great, and I'm also going to put in here because I know there's a lot with his biography, so I'm going to link to SAAM's website where it has a little bio about him. Okay, some other questions people are asking are, what was the criteria used to select the 29 pieces for this exhibition?

- (Keara Teeter) Well, it's something where it was a conversation, so it was a conversation between the Curatorial Department, Registration, Conservation. Conservation, part of the reason why we're doing these types of surveys and condition assessments is because since these pieces are being selected for a traveling exhibition it's not just going to be in-house, it's going out on loan, and so we needed to assess whether these artworks were stable enough to go out on loan and what we would need to do to prepare them for that. And a lot of those initial conversations actually happened before I came to SAAM, so I came in and was involved with the survey and the treatment aspect of it, but the initial conversations actually predated my time here.

- (Laura Hoffman) And also I know because you and I have been working together on a blog post that I'm going to put in here as well, but you had told me that the number actually changed, right? It had started out...

- (Keara Teeter) It did.

- (Laura Hoffman) ...as 27, and then became 29 in the time of your fellowship?

- (Keara Teeter) So it started out initially as 28, and then one was removed from the exhibition checklist, and then at that point I hadn't even had the opportunity to survey that one yet, so it was actually removed before I did my survey, so I never looked at that painting in person. And then two additional ones were added recently in the past number of months, so it's something where depending on what type of story is being told through the exhibition and what types of characters and individuals and historical scenes are being represented, it does change the checklist for the exhibition.

- (Laura Hoffman) And I think something to just keep in mind, you know, us being in the museum field and seeing it, is checklists. There's always this framework and it's worked on, and, you know, it's this living, breathing document that changes based on, you know, what the conservators say after they do condition reports and/or all these other factors from other departments, right? So it'll be interesting to see, you know, what all goes out when it is. I think the exhibition is planned for 2023, right?

- (Keara Teeter) So it's actually going to premiere at the Gibbes Museum [of Art] in South Carolina, but then it's projected to come back to D.C. and be exhibited at SAAM in 2023.

- (Laura Hoffman) Great, so I can't wait to see it. We've got a lot of questions coming in. Another question is mentioning that William H. Johnson had sold and created many landscapes as well, and that's a very different aspect to his artwork.

- (Keara Teeter) Mhm.

- (Laura Hoffman) And the question is, did his "Fighters for Freedom" series provide a significant part of his income as the landscapes had previously done?

- (Keara Teeter) That is a really great question, and as far as the specifics on the finances, Curatorial might be able to answer that a little better, but it is something where this was done very late in his life. When he came back to the U.S. he actually, because he and his wife left Europe partly because of the Nazi power starting to gain momentum, and because of what was happening over there, they actually came back without a lot of financial foundation in place. So when he was creating these works, it was something where he was not in quite the same place as when he was creating those landscapes in Scandinavia.

- (Laura Hoffman) And just another question people have in trying to make out the timeline about William H. Johnson, what was he doing during World War II specifically, because a lot of these "Fighters for Freedom" was right after, right, the War ended?

- (Keara Teeter) Mhm. That, that's a great question. I...

- (Laura Hoffman) I'm asking you...yeah, I'm asking you all the hard ones.

- (Keara Teeter) I actually...I don't have a specific answer for that related to the War because I did look into his biography and his timeline, but I'm not sure exactly what he was doing in response to the events that were happening in Europe at that specific time. I would have to go back and look into that some more.

- (Laura Hoffman) Fair enough, and I did include the bio so we can all do our own research on him. His life was super fascinating. We are getting some questions about some of the work that you did, so I think just before I transition that, something that is helpful to learn about is someone was asking why his style is so different between his self-portrait that you mentioned in college to this "Fighters for Freedom" series. So maybe if you kind of go back and just show that again because it is very different.

- (Keara Teeter) His style changed dramatically throughout his artistic career, so you can see his painting style was very academic when he was at the National Academy of Design. Later on, the other self-portrait that you see on this slide was painted around 1937, and you can see that's much more of like an expressionistic style. He also when he was in Europe he was painting...some of his works were more like impressionistic in style, so his application of paint and his use of materials changed dramatically from each period of his artistic career. And the "Fighters for Freedom" series, by the time that he's creating these artworks, you can see that he's actually creating more of a two-dimensional space intentionally and not having as much of that modeling.

- (Laura Hoffman) So staying on this slide because there's a question specifically about these three is, what medium are these paintings?

- (Keara Teeter) These, these three are all oil paintings, but he painted them on...two of them are listed on paperboard, one is listed on fiberboard, and it's something where the paintings in the series that I've looked at have all been on solid supports rather than fabric supports, whereas earlier he was creating works on fabric supports like canvas or burlap. But at this point he not only is changing, you know, his artistic style and what he is featuring as subject matter, but he's also changing the type of supports that he was using to paint on.

- (Laura Hoffman) So a question that came through as well, speaking about these paperboards, is why do you think that he used paperboard and not some other substrate?

- (Keara Teeter) At this time part of it was what materials were accessible to him. As I mentioned, when he came back he did not have as much financial support as probably would have been desired, and so a number of the materials he was using like the paperboard-or there's some that were on Masonite or very, very thin plywood-a lot of those materials were materials he had access to.

- (Laura Hoffman) So a follow-up question someone asked is, how will these age being on this type of paperboard support? How is that different than the fabric-based canvases that you had talked about?

- (Keara Teeter) So I'm actually going to scroll ahead a little bit, and you can see here. So earlier on when I had the condition diagram you were able to see that there were some areas that had corners missing, and here you can see a detail from a during-treatment and after-treatment comparison, and it's something where the paperboards that he used, they were not made out of like a pure cellulosic material, so basically they had a component in them called lignin which is kind of what...like if you're looking at old newspapers, and you notice how they turn yellow or they get brittle over the course of time that they're aging. That is because of the lignin that's in the support, and a lot of these materials, all of these paperboards, have that. And so as they're aging they're becoming more brittle, and they're becoming easier to accidentally damage, or potentially for some of the ones that didn't have frames they don't have that additional protection of a frame, and so it's something where that's something that we've had to be very attentive to.

- (Laura Hoffman) So for this one, it didn't have a frame?

- (Keara Teeter) This one did not have a frame, and you can actually see in the image of me working I actually have it just supported up on the easel because the paperboard was so thin, and it didn't have a frame when I was actually treating it. But, one thing that we have been doing is I've been working with the frames conservator to create new frames, and so this is just a mockup to show you how they would look. And so we're actually creating a molding on the side and a collar on the back to create some depth so that there's enough cavity to fit the painting, and then there is a layer of what we call "glazing," which for your frames at home that would be either glass or acrylic and then a liner to space, to add some space, between the glazing and the painting. And then we also for some of them, this piece in particular, we had a backing support that was an aluminum composite material basically because the paperboard was so thin and there was damage to that lower edge. Keeping it upright in a frame without any additional support would have been problematic, and so we added that. And then we're actually when they go out on loan we're going to be creating a package where we're going to be adding this barrier layer to help seal in the painting. That way when it's traveling it's not going to be exposed to like changes in humidity or pollutants or other things. Those are not going to be able to permeate through this barrier layer, and so it's going to be protective.

- (Laura Hoffman) And so is this a different type of frame knowing that these artworks are all going to be travelling than if they were just staying here at the museum?

- (Keara Teeter) Yes and no. So for the artworks that already had frames we are retrofitting them, so for the ones that already had frames that didn't have glazing, that didn't have like a microclimate package, we're adding that material. But for the ones that didn't have frames, we actually didn't have any more of the molding from the framing that was done previously, so we actually had to do our research and find a frame molding that was comparable and would match aesthetically the other frames on the Johnson paintings. And so this was the model that we chose, and we're making it work. There was about...so out of the 29 paintings I looked at, 12 of them did not have frames, so that's a large number of paintings that needed new frames.

- (Laura Hoffman) So as a painting's conservator, is that pretty typical that the paintings you're working with may not have frames on them?

- (Keara Teeter) It all depends on what collection you're working with. When you're working in a museum, depending on the artist you're working on, a lot of them may have frames. Some of them may be frames that were made or originally added by the artist. Others are frames that were not originals to the artwork, but were added later on. If you're a conservator that's not working in a museum and you're working privately, then it all just depends on what comes into the studio, so...

- (Laura Hoffman) It sounds like me on one of my tours. I always say, "Oh, it just depends. It depends," but it's so true with conservation, right? It really...that's why we like to call you guys "art doctors" because you're thinking about each artwork as an individual patient and what it needs, right, especially given the context. So for these going off and being travelling, you need to take other precautions that will make sure that they will safely travel. So we have some questions here. Someone's asking about, what is the panel made of that you mentioned? I know these are all traveling, so when you're looking, let's look at this specific one because I know this one here is one of the travelling pieces. What is the panel made out of?

- (Keara Teeter) The original artwork support? Okay, so that one was made out of paperboard, and that paperboard was three-sixteenths of an inch thick. So it was very, very thin.

- (Laura Hoffman) Do you want to hold up with that with your hand so we can kind of get a sense, give or take like this?

- (Keara Teeter) Oh, I mean, it's very, very thin.

- (Laura Hoffman) Very thin.

- (Keara Teeter) I could get out a measuring tape, but...

- (Laura Hoffman) That's okay.

- (Keara Teeter) People could also do that from home, so...

- (Laura Hoffman) Yes. So then, a question about this paperboard. Does any of the paperboard have a high-acid content that would interact with the painting material?

- (Keara Teeter) So it's something where that is a potential depending on what type of pigments or what type of medium is being used. That's actually something I'm really excited about learning more of this upcoming year. We're actually working with some Smithsonian scientists over at the museum Conservation Center, and they're helping run some analysis for us on some small paint samples that we've collected to help provide us with more information about what pigments were used. And that informs not only research, but it also informs treatment and preventive care going forward as we're trying to preserve these collections in the long term.

- (Laura Hoffman) Well, speaking of that, because I know also the slide you have up here shows before inpainting and after inpainting, so speaking about the original paint, and then here, I mean, I can't even see looking at this the difference, so are you using the same paints? And specifically a question is, what types and brands of paint have you been using for this, for these...

- (Keara Teeter) Okay, so I am...I'm going to do two things. I'm going to show you a couple of things, and I'm going to scroll through here. So this is an overall before and after, and then this is actually the area so that you can actually see where my inpainting was done. Here's the area in normal light or visible light what a human can visibly see on the top and then under ultraviolet light or ultraviolet radiation on the bottom, and my retouching, my inpainting, is actually showing up dark. And then I'm going to stop sharing for a second so that I'm large.

- (Laura Hoffman) I'm going to then stop my video so that you can...we can see you big.

- (Keara Teeter) Okay. And so for the types of materials that we're using, basically we have different inpainting media depending on what we're working on and what our goals of the treatment are. So this is an example of one pallet that I would use for a painting like this. We have different types of media depending on what we're using, but all of the materials are high quality, like conservation grade, paints that are not the same as the original. So in this case the original was an oil paint, and what we're using is chemically different. That way, not only has this material been...not only has it been artificially aged to make sure that it has like good long-term characteristics for light stability and cohesiveness, but it's also something where it's chemically different so if my work needs to be undone by another professional in the future they have the documentation showing exactly what I used, and they also have the information and the knowledge to be able to reverse that safely without affecting the original painting. Something else we do, I'll just pull this over really quick, is we create mockups before we actually start working on the artwork itself. So this is just an example of mockups and the different types of fill materials. If there was like a gouge and you need to actually add something to bring the level up to plain with the rest of the paint layer before you add the color, then you would need to test fill materials and then test paint materials before you actually work on the original artwork.

- (Laura Hoffman) So speaking of that, and I know you'll probably get back into your slides, so I'm just going to ask you a question as you do that, for these, that's a lot of work that you do, so for the artworks, how long does it take you to do, to treat, to fully treat, one of these paintings?

- (Keara Teeter) Well, that also depends. It's something where when I was doing the survey I actually...after doing the survey I actually planned out and did a spreadsheet for which ones were high priority for treatment and which ones were medium priority and which ones were low priority, and the low priority paintings, depending on the work, might have only been a couple of hours, maybe half a dozen hours, but the high priority paintings, a lot of them were actually over 80 hours for just the painting treatment. That does not include having to make the frame. And so it's something where it really does depend on each individual artwork.

- (Laura Hoffman) And just because people might not be familiar, like 80 hours sounds like a lot to me. Is that pretty long for a conservation treatment, or is that, you know, pretty standard?

- (Keara Teeter) So it's something where, like I said, compared to the shorter treatments it definitely is much longer. It's something where a treatment like that can easily take a year because you're not working only on that painting every day that you go in. So if it's 80 hours, you're not getting it done in two weeks, at least in most cases because you're working on other paintings. You're not just working on that one painting, and not all of the work that conservators do is hands-on treatment. Some of it's report writing or doing surveys or assessments. I do public programming events like this. I also have other meetings within the Conservation Department and within, you know, cross-departmental meetings, so it's something where only a portion of my workweek is actually hands-on treatment, and then a portion of it is divided up into other tasks.

- (Laura Hoffman) That makes sense, and I do know, especially when you're talking about working with MCI, the Museum Conservation Institute that's through Smithsonian, you're waiting for new research to come in, so it's this kind of song and dance with it. So a question about that you just showed us all those paints are, how do you match the colors in a repair?

- (Keara Teeter) Well, it's something where you need to take a lot of things into consideration. One of those is what type of light you're painting under because what I'll do is to paint I actually use something like these. These are OptiVISORs. Basically it's like a headband that has magnifiers so that I can work up close, and I'll use very tiny, very tiny paintbrushes.

- (Laura Hoffman) I mean, that's so small. It's even hard to see without even getting closer. It's tiny.

- (Keara Teeter) I don't know if my camera is going to focus on it that close, but it's something where it's very meticulous, detailed work, but I also have to pay attention to how the painting is being illuminated because different types of light...so, like, think about in your home. You might have warm light, you might have cool light, and different types of light actually will react with the paint and reflect off of it and be viewed visually differently. And so if I'm painting in one type of light, but it's going to be shown in the gallery with a different type of light, then even if my work looks precise and exact when I'm working on it, once it goes in the gallery it may not match anymore. So it's something where, in our case, we're very fortune because the Lunder Conservation Center's painting studio, the fourth floor, is actually...it has natural light. So we have natural light coming in from above, and then we also have gallery lights that we are able to set up in the space so that we get the color temperature exactly where we need it.

- (Laura Hoffman) And I know just from working there in the lab, I've seen, you know, you guys working and looking when you're doing inpainting you've gone back to it hours later to see what it looks like in different lighting.

- (Keara Teeter) Mhm.

- (Laura Hoffman) So making those changes and being...you know, I think the name of the game with your work is you've got to be really patient with it.

- (Keara Teeter) Absolutely.

- (Laura Hoffman) But there is a follow-up question about with the painting, not so much on the color, but thinking about how do you mimic the existing brush strokes when you do add inpaint for those inpainted sections?

- (Keara Teeter) With this particular piece, because the paint was so flat I didn't actually have to create texture, so I was mimicking brushstrokes just using different shades of color because, as you can tell in the painting itself, you can tell that he has a very streaky appearance, so I created that using different shades of color. But, if it was a painting that had more texture to it, then I would actually have to create that in my fill material so that not only do the colors match, but the texture match, because if the colors match but the texture doesn't, then it's still very visibly distracting, and it's something where we want to bring the piece back as close as we possibly can to the artist's original intent. And so it's something where in addition to doing the work that I do, we do have documentation like this for our records, but because we're trying to allow our visitors to view something without being distracted by damages that were not there when the artist initially finished the piece, that is the goal.

- (Laura Hoffman) I know it's a fine line too because you want to make sure that visually, as you said, it doesn't distract, but also you want to make sure that you're only working on the areas of damage and something that a later conservator with a trained eye could go in and be able to remove just safely your components to it. So it's always, you know, reassessing. I've seen you go back and forth working on it, which leads to a question that was asked which is...and I'm going to ask you to answer this within the realm of this project of "Fighters for Freedom."

- (Keara Teeter) Okay.

- (Laura Hoffman) Which is one of the more simpler treatments you've done, and which is one of the more complex artworks or complex treatments you've had to do for these artworks?

- (Keara Teeter) The simplest treatment that I've done so far for "Fighters for Freedom" has been a couple hours of inpainting where there were not very many damages, so I just had to do very light surface cleaning and then just a little bit of retouching to hit back those areas that were visually distracting, but then I was done.

- (Laura Hoffman) Are you talking specifically about this painting, or...

- (Keara Teeter) Not this painting, but within the "Fighters for Freedom" series. I actually don't have an image of...

- (Laura Hoffman) If you tell me the name, I can put it in the chat.

- (Keara Teeter) Oh, sure. So it was a painting of "King Ibn Saud," and I believe the number for that was 1967.59.661, but there were two of the same person, so if that's the accession number for the other painting, then let me know. But that, oops, that is the smallest treatment that I did. The smallest, or the least time-consuming thing, that I did in total for the "Fighters for Freedom" series was actually when I didn't have to do treatment, and I just had to do photo documentation. And then the more extensive treatments were treatments like this one where it required structural treatment as well as aesthetic compensation and working to create a frame because it did not have a frame when it was originally assessed during my survey.

- (Laura Hoffman) I'm bringing it up here. I found both, so I'll put that in, but in the meantime I'm going to ask you another question. So a question...now, you talked a lot about the inpainting and the fills that you did. Have you done any surface cleaning for these works, and if so, how do you go about doing that?

- (Keara Teeter) I have done surface cleaning for these works, and it's something that because these paintings don't have an overall varnish on them-Johnson did apply varnish, but he only applied it to select elements or features in the paintings-I'm starting with dry surface cleaning using non-abrasive sponges. And then I'm actually going in to wet clean with water-based systems, but I'm not using anything that...I'm not using any very strong solvents because it's not a situation where I'm trying to remove a varnish. I'm just trying to remove the surface dirt and grime from the paint layer, and I don't want to use anything too strong.

- (Laura Hoffman) And about that, well, someone just asked...this is just a fun, quick question to ask you. Do you, yourself, paint?

- (Keara Teeter) I have not painted for myself in a little while. Part of that is I did paint a lot in the past, but part of that is I don't have my paint supplies with me here, so if I did have it then I absolutely would be painting a little bit more in free time, but I have been keeping myself busy doing other types of art projects like sketching or embroidery since I do have those materials.

- (Laura Hoffman) I mean, that is a good thing to note that, you know, you recently a year ago graduated from your graduate program at University of Delaware, and in that training you did have to take fine arts classes. You took chemistry classes, you took, you did, you learned all about art history and also the fine arts so that you could work on these artworks and make it look-mimic, as you said-the artist's original style.

- (Keara Teeter) Absolutely, and as part of my application to enter that graduate program, I did have a portfolio of works including paintings and other works, and so it's something I very much have enjoyed painting, but I'm just not doing very much of that actively in my free time at the moment.

- (Laura Hoffman) So a question for you, because this is a lot, like 29 paintings to go through, and I know you said that not all of them need the same amount of treatment, but how have you been prioritizing treatment, and were there some areas of damage that you addressed over others or were prioritizing first?

- (Keara Teeter) So the priority first was to treat the paintings that had the most significant structural issues, which many of those were the paintings that did not have frames, because when you think about it, the frame would provide additional support and protection, and so many of those paintings that were not framed would require more hours of treatment, and those were the ones that we brought to the Lunder Conservation Center first. But, at the same time, it's something where since we do have so many paintings I am trying to move them all along to the best of my ability. We also had a summer intern here this last summer that was mostly virtual due to Covid, but she actually was able to get in for a few days towards the end of her internship. And she currently is at the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program and was doing her internship with us for her summer, and she was actually able to work, get her hands in on some of the treatments as well, which is really great.

- (Laura Hoffman) That's excellent. I know she did a lot of research on this as well.

- (Keara Teeter) Mhm.

- (Laura Hoffman) So a question too about your treatment is, are any of the materials friable-maybe you can explain what that means as well for people who might not be aware-and how do you stop further deterioration if there is friable material?

- (Keara Teeter) So for those of you who may not be familiar with that term, "friable," when we're talking about, like, paint, "friable" would mean material that paint flakes that are either like cupping up and flaking off or that are just powdery and are just not well adhered and well attached. So it's something where it had both, or I've seen both in the paintings, on the backsides of some of the paintings because Johnson did paint the front with his composition, but he also painted the backs of a lot of these paintings with just a solid color, and the backs of some of them are having that cupping or that concave raising of edges, and then the paint flakes are falling off in large clumps. And then on the backs of other paintings and on the front of some paintings there is that powdery friable paint where it's just under bound which basically means that the pigment, the paint pigment, is bound in a medium that holds it all together, and if it does not have the...enough of the pigment-to-medium ratio then it is able to separate more easily. And so I'm actually going to have, I have to go in and add a conservation-grade adhesive basically to help keep all of that together, and so I've had to deal with that for many of the paintings.

- (Laura Hoffman) Well, a question that came in, and I think this works well with it, is, were any of the paintings that were supposed to be in this show deselected because of too great conservation concerns?

- (Keara Teeter) That is an excellent question, and as far as the paintings that I saw at the point that I came in on the project, the one that was removed was actually not removed for conservation concerns. It was removed for other reasons. But, a lot in other cases, in other exhibition checklists, paintings will be removed for conservation reasons, and I'm not sure if it happened with this project before I came to SAAM or not, but by the time that I came on and started the project the checklist was mostly finalized, and so the one that was removed was not removed for conservation reasons.

- (Laura Hoffman) Well, I have a couple...there's some questions also just thinking about these different pieces too. I know this one here, maybe you could talk a little bit about it because there's been a couple questions asking about the women featured in the "Fighters for Freedom" series. We saw before that there was the "Harriet Tubman" I think you showed at the beginning.

- (Keara Teeter) Mhm.

- (Laura Hoffman) But maybe you could talk a little bit, "I know this one, and there are other instances." I don't know if you know offhand how many, but just the ones you can think of.

- (Keara Teeter) Offhand, I don't have a number for that, but I can throw out some examples. So for this one, this one is titled, "Historical Scene with Mary McLeod Bethune," and it's featuring Mary McLeod Bethune who founded what is...this piece was based on Bethune-Cookman College [University] which she helped found, and she actually was the first college president there. And this college is an HBCU, an Historically Black College and University, and at the time that she was president she was the first African American woman to be president of a college in the United States, and she later went on to be involved in many other very important initiatives including the NAACP, and she was an advisor to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. So she was a woman who struggled for, or she was known, as the woman or the "[First] Lady of the Struggle" because of all of her activism in civil rights issues.

- (Laura Hoffman) Well, that's great. I mean, it's already 6:15. I wish we could keep talking about it. I do want to say, I'm going to put in here your blog post because I know it does talk a little bit more. I also want to add in some links because we do have some upcoming Converse with a Conservators. Our next one is going to be on Wednesday, December 2nd, and that's going to be on Folk and Self-Taught Art. Also, please fill out the survey so we can learn more about what you want to see and hear. Keara, it was a pleasure talking with you. I...we might have to do another blog post. There's just so much with this series. I can't wait to see the exhibition. If you guys have further questions, feel free to email me, and I'll put you in touch with Keara. So just thank you so much, and enjoy the rest of your evening. Bye, everyone.