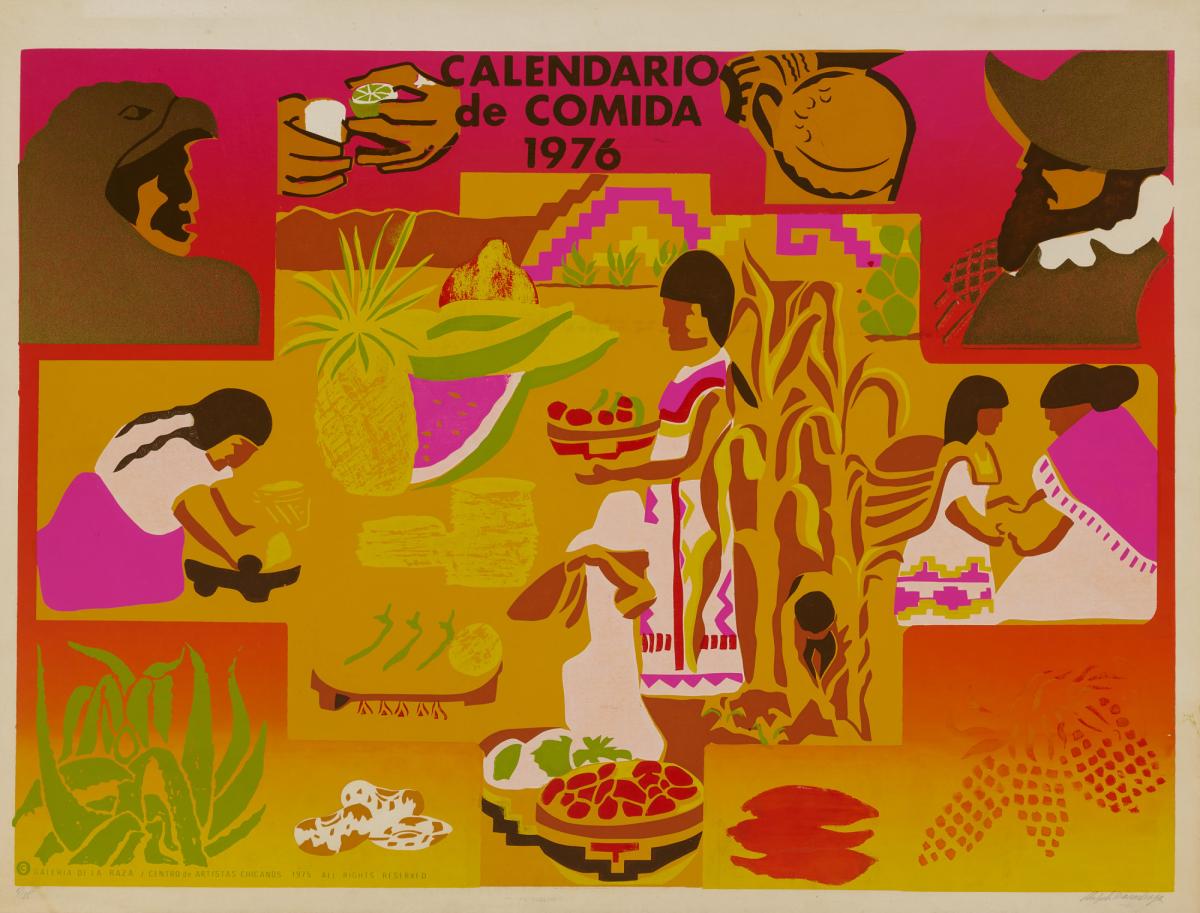

In 1976 the Royal Chicano Air Force (RCAF), a California-based art collective, collaborated with Galería de la Raza in San Francisco to release the Calendario de Comida, a print calendar entirely devoted to food. Decorative, yet functional, Chicano artists frequently chose the calendar format for its familiarity and usability. As ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now curator E. Carmen Ramos explains in the exhibition catalogue, the calendars were sold as fundraisers, while also serving as a vehicle to tackle cultural and political subjects.

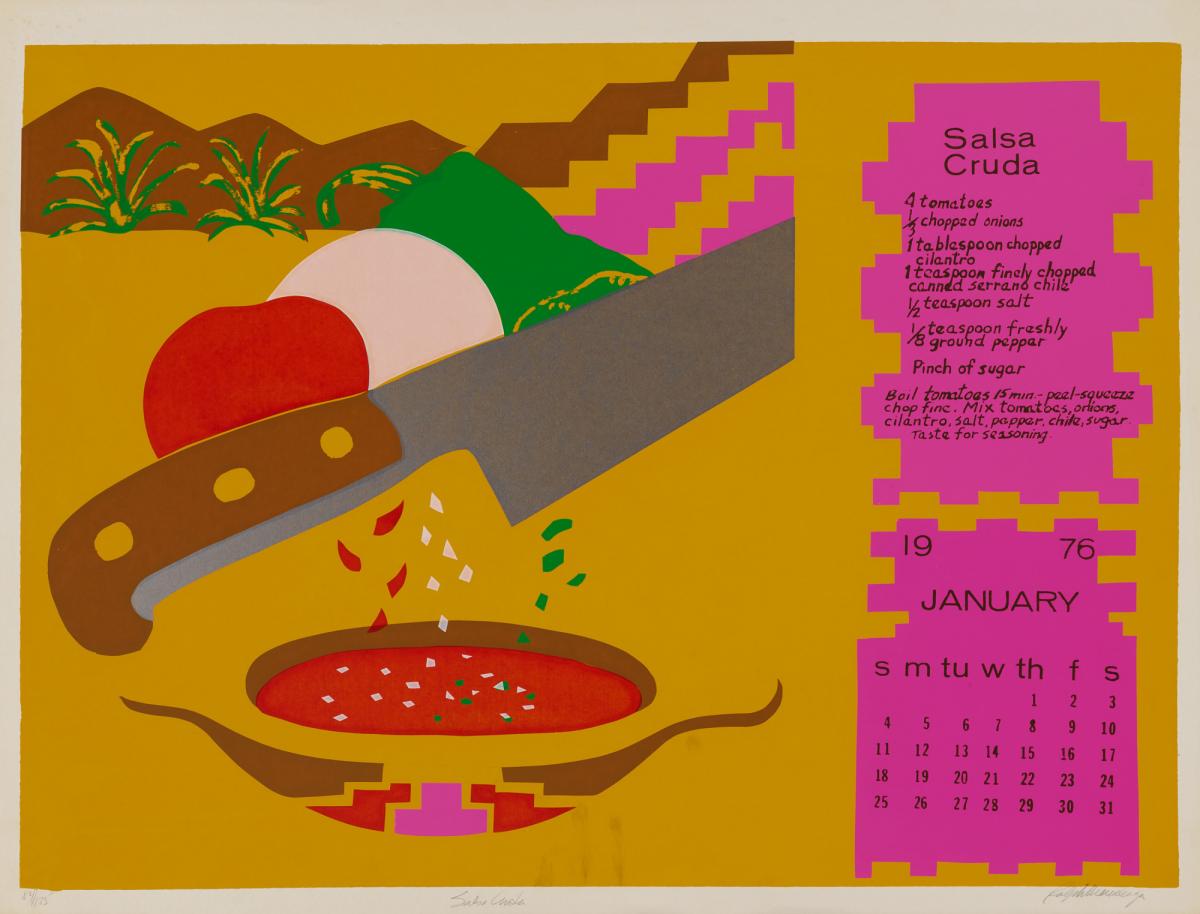

The Calendario de Comida presented vivid graphics simultaneously rooted in Mexican heritage and contemporary Chicano culture, featuring traditional foods that were staples since before the conquest and dishes that would be familiar in Mexican American households in the U.S. Salsa Cruda, featured for the month of January, illustrates a knife cutting into tomatoes, onions, and chile peppers, arranged to echo the colors of the Mexican flag. Beside the graphic is a recipe for salsa. The recipes, including chorizo and pan dulce, give the calendar another level of function that would have been valuable in the household.

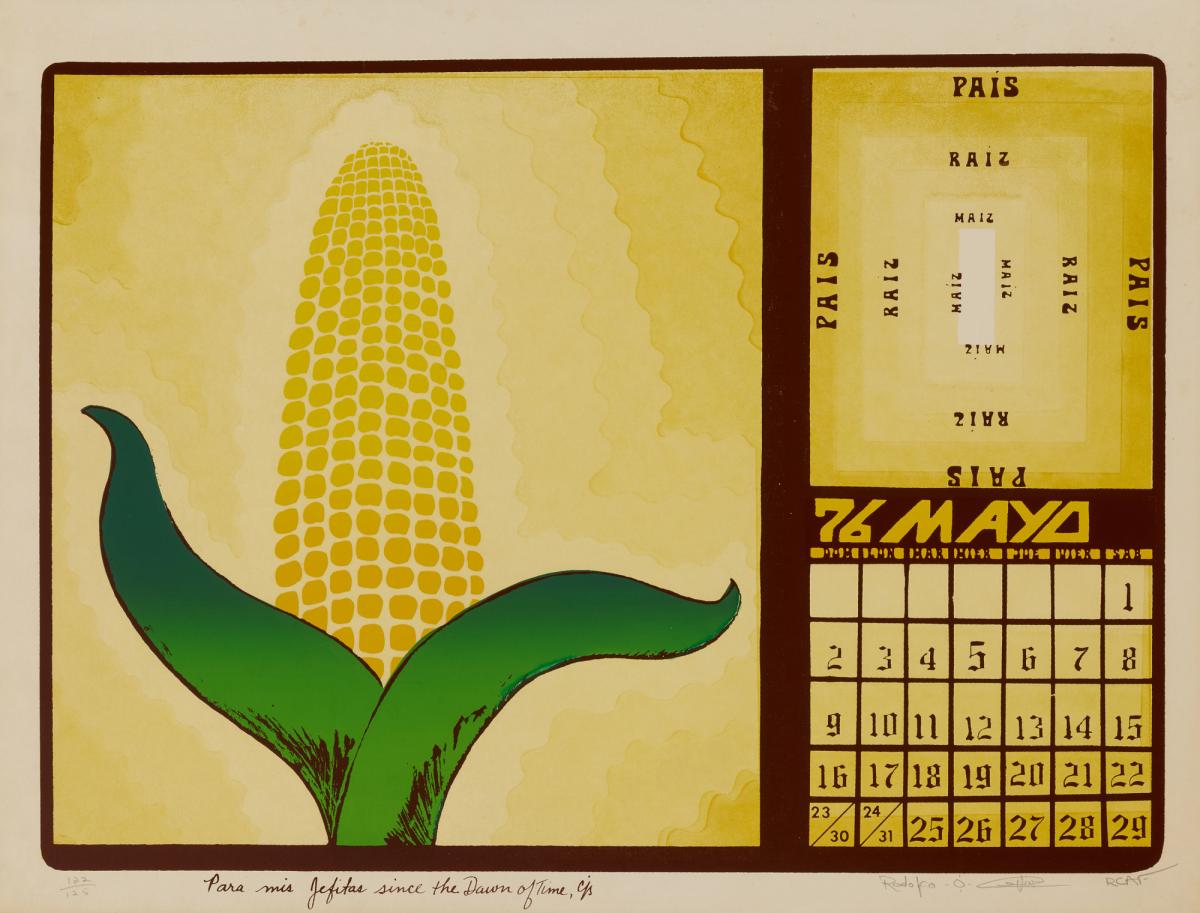

Food motifs and bilingual text are combined with Mesoamerican iconography throughout the calendar. During the Chicano civil rights movement of the 1960s and 70s, known as El Moviemento, Chicano artists drew from imagery and traditions that emphasized their indigenous roots. The calendar also honored the role of women as the bearers of tradition, as seen in the image for May, Para mis Jefitas since the Dawn of Time. In the image, a single stalk of maize, arguably the most important crop of Mesoamerica, is a tribute to “mis jefitas” (important, strong women) and links together the women who have fed their families over thousands of years of history.

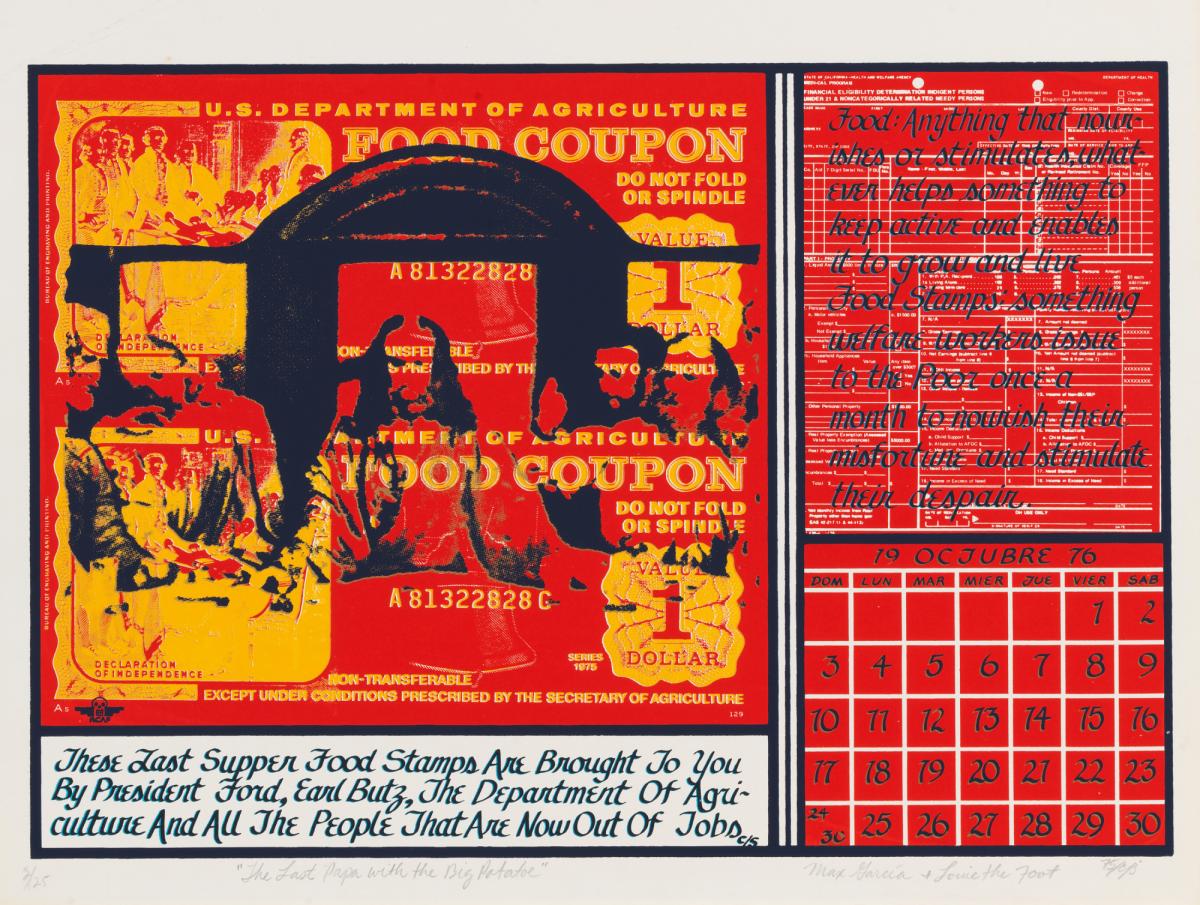

The calendar also commemorated the community’s sense of place, and struggles, highlighting historic establishments like La Victoria Bakery in San Francisco, one of the Mission-districts oldest Mexican owned businesses. Esteban Villa's image for August, Yerbabuena, depicts both the herb native to California, as well as recalls the 1846 Battle of Yerba Buena, in which the U.S. Navy captured the town of Yerba Buena (now known as San Francisco) from Mexico during the Mexican-American War. Other images, such as The Last Papa with the Big Potatoe (October), reference social justice causes. The image overlays fragments of The Last Supper over a food stamp. As Ramos describes, the calendar “humorously acknowledged how the poor relied on food stamps during hard times, effectively interweaving tradition, place-making, and class consciousness in a single series.”

SAAM’s landmark exhibition, ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now, explores how Chicanx artists have linked innovative printmaking practices with social justice. This blog post is part of series that takes a closer look at selected artworks with material drawn from exhibition texts and the catalogue.